Trump Confusion Syndrome

-

John Mauldin

John Mauldin

- |

- February 14, 2025

- |

- Comments

- |

- View PDF

I think I’m going to start a new 12-step program. I sense there are a lot of potential members. The meetings would start with something like this:

“Hi. My name is John. I have Trump Confusion Syndrome. I don’t think it’s contagious, but many of my friends are suffering similar symptoms.

“I like a lot of what the new Trump administration is starting to do. But then the president announces head-scratching moves like steel tariffs and then general tariffs which seem counterproductive for the economy. I end up feeling like Alice in Wonderland’s Red Queen, trying to believe six impossible things in my head before breakfast.

“Of course, I know Trump has a different leadership and negotiating style. I get that. My confusion stems from trying to figure out which is the negotiating part, and which is just bad policy.”

Trump Confusion Syndrome, or TCS, is distinct from Trump Derangement Syndrome in which afflicted people feel outrage about everything the president says or does. TCS isn’t about agreeing or disagreeing. It’s mostly about understanding. And then when something still seems wrong, feeling free to say it out loud. Yes, there are certain circles where disagreement is frowned upon.

Part of the TCS problem is that Trump’s style creates confusion. This method seemingly has worked pretty well for him, too. The problem: It works only by keeping everyone confused—even some of his own supporters.

Now, we could debate whether this is the best strategy a president can follow. That might be academically interesting. But as of now, Trump is the president and this is his way. It is unlikely to change. All we can do is deal with it. And in the spirit of full disclosure, I am quite happy that they are actually finding out where our money is spent (which is creating confusion). That process requires full internal audits be made public which has just not been done. We are finding a lot of problematic expenditures and outright fraud and waste. And we’re just three weeks into the process.

But the tariff thing? This is more problematic.

That being said, I think we will learn how to manage this. It’s not going to change the bigger trends I’ve described. AI, robotics, and biotechnology are going to radically change how (and how long) we live, a debt crisis is still coming, and new generations will rebuild society’s core institutions.

But meanwhile, prepare to be confused.

Upfront Costs

For me, the top source of confusion is the president’s tariff fixation. Shortly after taking office, he ordered broad-based new tariffs on imported goods from Canada, Mexico, and China. The first two are now in a one-month pause; the China tariffs are now in effect (and China is already retaliating, too).

This week the president ordered a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminum imports. He promises more is coming.

To be clear, I endorse the goals of rebuilding US manufacturing capacity and making global trade fairer. No arguments conceptually there. I’ll even concede that using tariffs as negotiating leverage may help achieve those goals. But as we will see, the threats themselves have costs even if reversed or softened.

The policy question, then, is whether the possible benefits outweigh the near certain costs. I say “near certain” because the impact was measurable when we went through this in 2018. Here’s how The Wall Street Journal editorial board (which is generally supportive of Trump) described his previous tariffs.

“Consider Mid-Continent Steel and Wire, which produced roughly half of the nails made in the US. After the steel tariffs took effect, its sales plunged by more than half, causing it to lay off 80 workers. Another 120 quit because they worried its Missouri factory might close. After this damage, the Commerce Department granted the company a tariff exemption.

“Auto makers were another casualty. Ford Motor said tariffs subtracted $750 million from its bottom line in 2018, which reduced profit-sharing bonuses for each of its workers by $750. GM said the tariffs dented its profits by some $1 billion, equal to the pay of more than 10,000 employees.

“The tariffs also made US manufacturers less globally competitive and prompted retaliation that hurt American businesses. Canada imposed tariffs on $12.8 billion in US products, including 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum. Harley-Davidson shifted some production to Thailand to avoid Europe’s retaliatory tariffs on US motorbikes…

“Employment in durable goods manufacturing began to decline in early 2019, which reduced demand for steel and aluminum. Employment in fabricated metals manufacturing that used steel and aluminum plunged and is still some 35,000 lower than when the tariffs took effect.”

It’s possible these upfront costs might have eventually paid off. We don’t know because COVID-19 intervened, sending the economy in an entirely different direction. But now it seems (remember, we aren’t entirely sure) Trump is about to run that same playbook again. If it is, in fact, a negotiating strategy, the previous experience suggests he won’t mind keeping the tariffs in place for a year or more while trying to get concessions from the other countries.

In that episode, the administration sought to minimize domestic damage by granting exceptions for many US companies. Something like that may happen again. But this still takes time and adds more confusion to an already complicated business environment.

We need to actually look at those exemptions for a minute. From what I’ve read, many if not most of those exemptions were something called “tariff rate quotas” or TRQ. Those “TRQs” allow a certain amount of products to enter duty-free before the 25% takes effect.

Biden continued the process of TRQs and granted numerous exemptions. Further, the White House points out that both Russia and China would ship steel to Mexico or Canada and then come in duty-free. The TRQ use allowed Japan, Korea, and other countries to ship steel products under the quota. The White House (correctly) contends this is not what was originally intended. That is all going away.

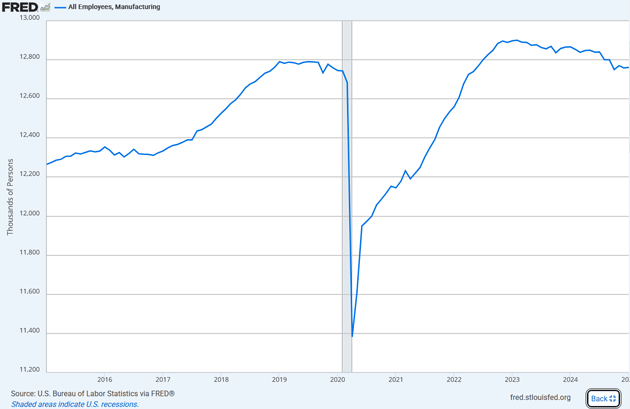

Let’s look at what is actually happening to manufacturing jobs, from the St. Louis Fed’s FRED database:

Source: FRED

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

Sidebar: You have to be careful when you read articles that say 200,000 (or whatever number) manufacturing jobs were lost under Trump. They take them from his first month in office to his last month in office. However, this includes COVID job losses. Shortly thereafter we had more manufacturing jobs.

Moving on, there are a lot of explanations for declining US manufacturing employment. I think it comes down to price, creative destruction, and job desirability. We lost a lot of apparel manufacturing jobs. Have you seen the pictures of clothing sweatshops? And they did not get paid that much. Who really wants to be on an assembly line of iPhones doing the same chip insertion eight hours a day? Even the Chinese are shipping those jobs offshore. A lot of the so-called manufacturing jobs we lost were simply not value-added jobs.

We did lose some better-paid manufacturing jobs to China, Europe, Brazil, etc. It’s a fact that it is just cheaper to manufacture some automobile products and do assembly in Mexico.

I want to be circumspect in how I say this. While I in no way want to suggest that Canada should be the 51st state, in terms of its reliability, access, and competitiveness, it functions similarly to what other states in the union do. It makes sense to have a free-trade agreement with them. I wish that Canada didn’t feel the need to protect certain domestic industries with tariffs, and I wish the US didn’t either.

Yes, there would be some creative destruction, but businesses in both countries would be able to sort that out just like businesses in the 50 states do.

“Costs and Chaos”

The steel and aluminum tariffs are a bit different from other proposals in that they don’t target consumer goods. None of us go shopping and come home with tons of steel girders. These are intermediate goods, used by manufacturers to make other things: automobiles, apartment buildings, pipelines, beer and soda cans, and so on.

Further, the new tariff proposals will not come with the exemptions that were part of the old proposal. This is a major shift. Thus, manufacturing company leaders are the first to speak out. And they’re not holding back, nor are they forgetting that the Canada and Mexico tariffs may still come back.

Here's Ford CEO Jim Farley speaking at an auto industry conference last week (h.t. Peter Boockvar). Emphasis mine:

"There's a global street fight in the auto industry right now between electrification, zone electric architectures, and of course, kind of the emergence of the Chinese as a global force in our industry. And I think President Trump has talked a lot about making our US auto industry stronger, bringing more production here, more innovation in the US. And if his administration can achieve that, it would be one of the most signature accomplishments.

"So far, what we're seeing is a lot of cost, a lot of chaos. If you look at the tariffs, let's be real honest, long term, a 25% tariff across the Mexico and Canadian border will blow a hole in US industry that we have never seen. And frankly, it gives free reign to South Korean and Japanese and European companies that are bringing 1.5 million to 2 million vehicles into the US that wouldn't be subject to those Mexican and Canadian tariffs. So, it would be one of the biggest windfalls for those companies ever. Meanwhile, we're USMCA compliant with almost all of our content, finished vehicles and components going across the borders to have that kind of tariff would be devastating.

[On the impact from the new steel and aluminum tariffs, which we know the auto industry is a heavy user of.] "So in steel, we get 90% of that from the US. We get about 10% from Canada and nothing meaningful from Mexico. Aluminum also is not that impacted for us.

"The reality is, though, our suppliers have international sources for aluminum and steel. So that price will come through and there may be a speculative part in the market where prices come up because the tariffs are even rumored. So we'll have to deal with it. And that's what I'm talking about, cost and chaos. It's like a little here, a little there. A couple of weeks or a couple of months of vehicles crossing the border, components crossing the border, that's going to be a tariff. This is what we're dealing with right now."

The good news is the companies see what’s coming and are working to mitigate it. The bad news is they could be putting that effort into making their businesses better and more efficient. Dealing with constantly changing tariff policies will be a giant distraction, at the very least. The more likely effect is that profits go down, as they did last time.

Other industries are affected, too. Steel and aluminum are critical to the energy sector, which Trump is encouraging to boost production and bring fuel prices down. That will be harder when, for example, the steel that goes into drill rigs and new pipelines gets more expensive.

Real-world example: I called Jay Young at King Operating who put me in contact with his rig manager, Kelly Duncan. Kelly told me that about 15% of the cost of the well is actually in the casing pipe. When he started his career 20 years ago it was almost all US pipe and he bought a lot from Lone Star Steel. It was a huge facility that I drove past many times in my life. It is now a ghost town horror movie set.

Foreign steel simply drove US pipe manufacturers out of business. Those jobs did go away. There is very little we now do in casing pipe manufacturing. Kelly now buys most of his pipe from Korea and Taiwan.

|

A 25% tariff will increase their costs $3–400,000 on a typical well. That transition happened under Obama. His suppliers have notified him prices will go up.

Dustin Meyer, senior VP of the American Petroleum Industry trade group, told the Financial Times, “Unleashing American energy requires access to materials not readily available in the US.” He wasn’t exaggerating, either. Some 40% of the industry’s rolled metal goods (pipes, well casing, etc.) is imported, mainly from Canada and Mexico.

Can US companies retool and expand to fill that gap? Sure. But not tomorrow, and probably not even this year. Would you invest multiple millions (?) in a new production line if the tariffs are going away a year from now? Businesses hate uncertainty. “Drill, baby, drill,” could turn into “Wait, baby, wait.” These increased costs figure into whether or not you’re going to drill a new well.

And waiting isn’t free. Postponing a business decision because some important element is up in the air, for reasons beyond your control, costs both time and money, not to mention opportunity. A variation on that theme is what made the COVID recession so deep.

Confusion = Risk

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

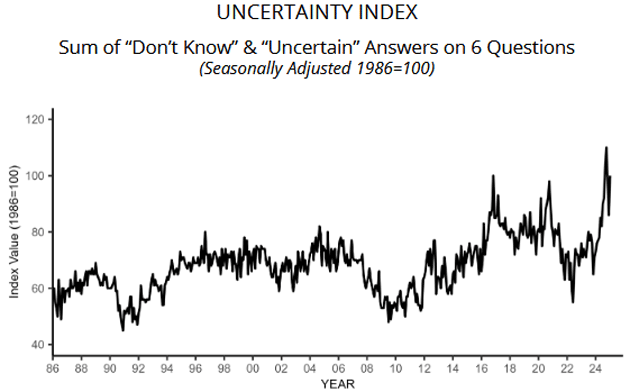

All this might be more manageable if the economy weren’t already in a confused, uncertain place thanks to inflation and interest rates. We can actually measure the uncertainty, too.

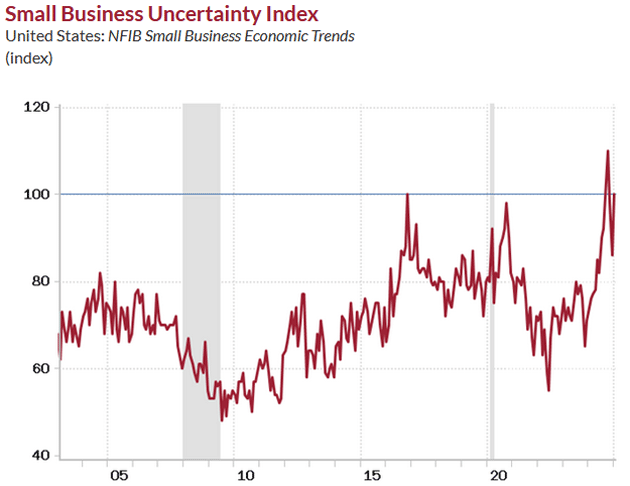

Each month the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) surveys its members about the state of their small businesses. They ask about employment, wages, sales, inventory, credit conditions, etc. On each of those questions, respondents have the option to answer, “I don’t know.”

The number who answer that way, observed over time, is valuable data. My friend Bill Dunkelberg, who runs the survey, compiles it into a “Uncertainty Index.”

Source: NFIB

Note, this isn’t a measure of optimism or pessimism. The uncertainty index was low in 2008–2010 not because conditions were good (they weren’t) but because everyone knew how bad it was.

Now we have the opposite situation. Uncertainty among small business owners is at an historic high point. Here’s another chart of the same data from Dave Rosenberg, zooming in on the last 20 years.

Source: Rosenberg Research

The NFIB Uncertainty Index climbed about 90 in July 2024, the first time it had seen that level since late 2020 when COVID was still raging. It went as high as 110 in October and was at 100 last month (January). It’s bouncing around but staying elevated—I suspect due to uncertainty about the political environment, inflation, and interest rates.

January's CPI data indicated that inflation is not improving and may be worsening, likely delaying Fed rate cuts that were already unlikely this year. But here again, everybody is confused. (My bet: Unless something changes, which would likely mean a softening economy so that would not be good, it is very possible we get no cuts or only one cut late in the year.)

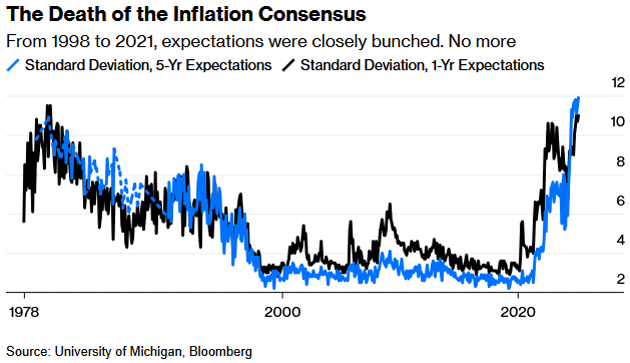

This uncertainty shows up in inflation data, too. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment survey asks people about their inflation expectations. Recently they have been all over the place. This chart measures the standard deviation, or dispersion of the answers.

Source: Bloomberg

A low standard deviation means answers are more tightly clustered around the average. For inflation expectations, this was generally the case from 2000 up to 2021–2022. Then the standard deviation zoomed higher, indicating the guesses were wider apart.

The broader point is that different groups of Americans have wildly different views of the economy, and this difference matters regardless of who is right. It affects their business, investment, and consumer spending decisions in ways we have not seen in many years, if ever. This adds even more uncertainty.

All this confusion was already in place before Trump took office and began brewing a trade war. And again, maybe a trade war is what it will take to solve some longstanding problems. But every war has terrible battles in which even the winners shed a lot of blood. Sometimes they’re necessary. But they’re always ugly.

If I were the president (God forbid) looking at this situation, I would probably try to avoid introducing yet more confusion during the first year of my term. It just seems extraordinarily risky.

But Trump is, if nothing else, a risk-taker. I’m sure he has been advised how badly all this could go wrong. But at that level, none of the decisions are easy or risk-free. He thinks tariffs are a risk worth taking, or at least worth threatening. We’ll know soon if he is right.

We have not even gone into the potential revenue tariffs would raise. That will come in a new letter, hopefully soon. There are better ways to go about raising revenue with fewer side effects. Stay tuned…

West Palm Beach, Dallas, DC, and Boca Raton?

Shane and I will fly to West Palm Beach in the middle of March, where I will be having dinner with David Bahnsen and Brian Szytel and the team at The Bahnsen Group with clients and prospects. I will likely quickly fly to Dallas where we will be soft-opening our new longevity clinic, quickly followed by clinics in Columbia, Maryland, Boca Raton, and Dorado Beach with West Palm and other clinics on the West Coast following.

I will also be in DC in late April for a small longevity conference, then the group will head to Capitol Hill to argue for changes in the way the FDA approaches aging. Since “aging” is not a “disease” you can’t submit a treatment for it. So you have to work around that by submitting treatments for symptoms. It’s time we treat aging itself as a problem to address. Plus a score of other important topics.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

Opening multiple clinics is exhilarating, exhausting, and terrifying. There are literally a thousand details that the team has to deal with, as well as the big-picture items. So many things have to work right in order to be successful. I console myself that I’m not trying to catch a rocket out of the air. We aren’t really doing something “new,” just bringing things together in a new and much more positive and efficient way.

It’s time to hit the send button. There was so much left on the cutting room floor in editing with this letter, but that’s why God made next week. In the meantime, you have a great week. And don’t forget to follow me on X.

|

Your needing more time in the day analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Put Mauldin Economics to work in your portfolio. Your financial journey is unique, and so are your needs. That's why we suggest the following options to suit your preferences:

-

John’s curated thoughts: John Mauldin and editor Patrick Watson share the best research notes and reports of the week, along with a summary of key takeaways. In a world awash with information, John and Patrick help you find the most important insights of the week, from our network of economists and analysts. Read by over 7,500 members. See the full details here.

-

Income investing: Grow your income portfolio with our dividend investing research service, Yield Shark. Dividend analyst Kelly Green guides readers to income investments with clear suggestions and a portfolio of steady dividend payers. Click here to learn more about Yield Shark.

-

Invest in longevity: Transformative Age delivers proven ways to extend your healthy lifespan, and helps you invest in the world’s most cutting-edge health and biotech companies. See more here.

-

Macro investing: Our flagship investment research service is led by Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino. His thematic approach to investing gives you a portfolio that will benefit from the economy’s most exciting trends—before they are well known. Go here to learn more about Macro Advantage.

Read important disclosures here.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

Tags

Did someone forward this article to you?

Click here to get Thoughts from the Frontline in your inbox every Saturday.

John Mauldin

John Mauldin