The Global Economy Looks Disturbingly Like Japan Before Its “Lost Decade”

- John Mauldin

- |

- April 18, 2019

- |

- Comments

By John Mauldin

After World War II, Japan experienced rapid growth as the US and others helped rebuild its economy. This led to a roaring expansion that culminated in the 1980s Japanese asset bubble.

It popped in the early 1990s bringing what came to be called the “Lost Decade.” It was really more than a decade, as the early 2000s brought only mild recovery.

GDP shrank, wages fell, and asset prices dropped or went sideways at best. Japan is still grappling with it today.

Now the rest of the world is approaching a period that may be an equivalent of Japan’s “Lost Decade.” It won’t be the end of the world, but it might be more painful than in Japan.

Japan had little growth due mainly to exports. That won’t work when every major economy in the world is in the same position. Plus, we are headed toward a global credit crisis I’ve dubbed The Great Reset.

Describing this decline as “Japanification” may be unfair to Japan, but it’s the best paradigm we have. The good news is it will spread slowly. The bad news is it will end slowly, too.

I believe we will avoid literal blood in the streets, but it will be a challenging time.

Japan’s Lost Decades

The Lost Decade had monetary roots.

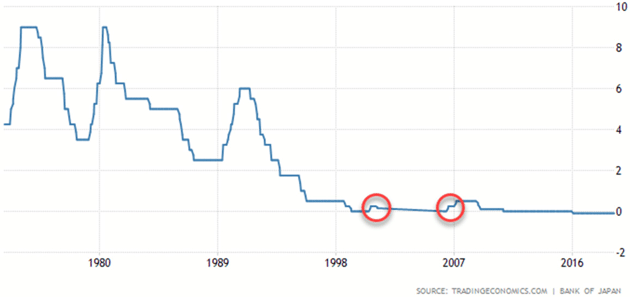

The 1985 Plaza Accord drove the yen higher and inflated the asset bubble. The Bank of Japan tried to pop the bubble with a series of rate hikes beginning in 1989:

Source: Mauldin Economics

Upon reaching 6% in 1992, the BOJ began cutting rates and eventually reached zero a few years later.

Since then, it has made two short-lived tightening attempts, shown in the red circles. Neither worked and that was it; no more rate hikes, period. Japan has now kept its policy rate at or near zero for 20 years.

The BOJ also resorted to large QE-like programs that also had little effect. Meanwhile, the government tried assorted fiscal policies: infrastructure projects, deregulation, tax cuts, etc.

They had little effect, too. GDP growth has been stuck near zero, plus or minus a couple of points. So has inflation.

That said, the BOJ’s asset purchases certainly had an effect. They more or less bought everything, including stock ETFs and other private assets.

Japan is a prime example of faux capitalism. All this capital is going into businesses not because they have innovative, profit-generating ideas but simply because they exist. That’s how you get zombie companies.

The result, at least so far, has been neither boom nor depression. Japan has its problems, but people aren’t standing in soup lines.

Not Working? Double Down

Many say the present situation can’t go on indefinitely, but there’s no exit in sight.

The Bank of Japan has bought every bond it can. Now they are buying stocks not just in Japan but in the US as well. They are trying to put yen into the system to generate inflation. It simply hasn’t worked.

When you don’t have a better answer, the default is to do more of the same. That’s the case in Japan, Europe, and soon the US. Charles Hugh Smith described it pretty well recently.

The other dynamic of zombification/Japanification is: past success shackles the power elites to a failed model. The greater the past glory, the stronger its hold on the national identity and the power elites.

And so the power elites do more of what's failed in increasingly extreme doses. If lowering interest rates sparked secular growth, then the power elites will lower interest rates to zero. When that fails to move the needle, they lower rates below zero, i.e. negative interest rates.

When this too fails to move the needle, they rig statistics to make it appear that all is well. In the immortal words of Mr. Junker, when it becomes serious you have to lie, and it's now serious all the time.

“Do more of what’s failed in increasingly extreme doses” also describes well the Federal Reserve policy from 2008 through 2016.

With little effect from zero rates, the Fed launched QE and continued it despite the limited success and harmful side effects. The European Central Bank did the same to even a great extent, also with little effect.

Which brings us to the next point: why Europe and the US will follow Japan.

Too Much, Too Fast

The Federal Reserve spent 2017 and 2018 trying to exit from its various stimulus policies. It began raising short-term interest rates and reversing the QE program.

In hindsight, it now appears the Fed tried to do too much, too fast. My friend Samuel Rines calculated that when you include the QE tapering, this Fed tightening cycle was the most aggressive since Paul Volcker’s draconian rate hikes in the early 1980s.

They should have started sooner and tightened more gradually. For whatever reason, they didn’t.

And so the complaints began. Wall Street wasn’t happy but, more important, President Trump wasn’t pleased with the rate hikes. But the real deal-breaker may have been the late 2018 market tantrum.

Then the yield curve inverted, coinciding with weakening economic data. That was probably the last straw. The Fed hasn’t exactly loosened, but there’s a good chance it will later this year.

Meanwhile, the ECB’s Mario Draghi had a tightening plan in place not so long ago. That plan is now out the door before Draghi is even close to gone.

So on both sides of the Atlantic, plans to exit from loose money now look disturbingly like those two little circles in the BOJ rate chart when it tried to hike and found it could not.

Worse, we are also replicating Japan’s fiscal policy with rapidly growing deficit spending. In fact, this year we will be exceeding it.

The Japanese deficit as a percentage of GDP is projected to be below 4% while the US is closer to 5%. And given the ever-widening unfunded liabilities gap, the US deficit will grow even larger in the future.

Turning Japanese, I think we’re turning Japanese, I really think so. (With a musical nod to The Vapors.)

The Great Reset: The Collapse of the Biggest Bubble in History

New York Times best seller and renowned financial expert John Mauldin predicts an unprecedented financial crisis that could be triggered in the next five years. Most investors seem completely unaware of the relentless pressure that’s building right now. Learn more here.