Private Equity: Too Big to Fail?

-

Ed D'Agostino

Ed D'Agostino

- |

- April 4, 2025

- |

- Comments

The trajectory of small businesses often goes something this: a first-generation entrepreneur starts and grows a company. It could be a software company, but also a plumbing, electrical, or HVAC business. If it’s successful (most are not), the entrepreneur creates jobs and maybe the kids get involved. But often, the kids go to college, pursue other careers, and the founder has no succession options. So, he sells.

To whom?

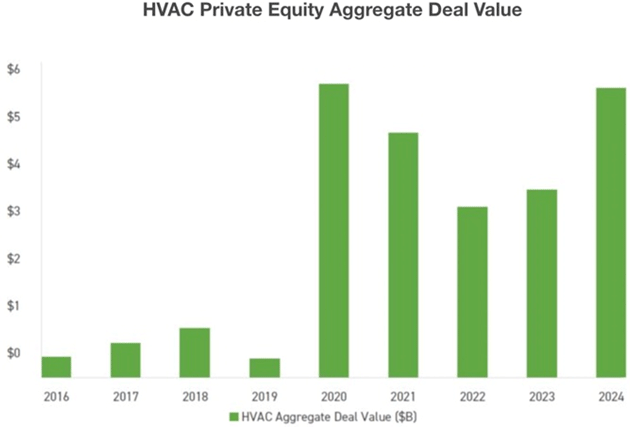

The answer, increasingly, is private equity, even if it’s a service business like plumbing, pest control, or HVAC…

Source: Cherry Bekaert

This is not necessarily a bad thing. I worked in M&A prior to helping found Mauldin Economics. Some of my clients were private equity groups. They would buy a company from somebody who wanted to retire, improve the business, then sell it to a bigger company in that industry. This is capitalism at its best.

This was 20 years ago, though, and the financial mechanics of private equity deals have grown more complex. Competition for deals has grown fierce as private equity assets under management have ballooned. The value of global private equity deals rose 14% in 2024 to $2 trillion, according to McKinsey. As a whole, private equity has become a massive portion of our economy.

My guest today on Global Macro Update, Brendan Ballou, noted “When you look at the number of employees that these portfolio companies employ, Blackstone, Carlyle, and KKR, not necessarily in that order, they would be the third, fourth, and fifth-largest employers in the United States behind just Walmart and Amazon.”

|

Private equity is the sought-after job for top business and finance new grads. My friend Jared Dillian calls it a bubble. There are plenty of smart people doing good work in private equity, but when self-help guru Tony Robbins is private equity’s new cheerleader, and Blackstone is buying smoothie shops, you have to wonder if things have gone too far.

I mentioned PE’s impact on small business because this is where many people will feel its impact firsthand. It will show up in prices and competition.

Demographics point to this dynamic playing out more over the next few years, as baby boomers—who still own 40% of US small businesses—look to retire.

However, the bulk of PE deals are much larger. Globally, the average PE deal size rose to $849 million last year. Bain & Co. reports that 77% of total deal value was for deals of $1 billion or more.

In our interview Brendan Ballou says the real trouble with PE comes from an impotent regulatory structure that incentivizes problematic decisions—and effectively absolves PE when things go wrong. This is the crux of his recent book Plunder, which grew out of Ballou’s work as Special Counsel for the Antitrust Division at the US Dept. of Justice.

In our interview you will also hear:

-

Why private equity doesn’t face the same oversight as Wall Street

-

Why private equity is targeting industries funded by government programs, including long-term care facilities, and how this impacts cost and quality of care

-

The corporate acrobatics that allow PE firms to exploit bankruptcy law

-

How private equity firms are shifting pension obligations, possibly onto taxpayers

To be clear, I am always an advocate for keeping regulation to a minimum. The best rules are simple, effective, and fair. Is that what we have for private equity?

For more, watch my interview the Brendan Ballou by clicking the image below:

A transcript of our conversation is available here.

|

And thank you, Global Macro Update readers, for your support.

Ed D’Agostino

Publisher & COO

If you prefer to listen to Global Macro Update, you can do so here:

Ed D'Agostino

Ed D'Agostino