Forecast 2014: The CAPEs of Hope

-

John Mauldin

John Mauldin

- |

- January 25, 2014

- |

- Comments

- |

- View PDF

The Second Most Expensive Stock Market in the World

Who’s Got Your Risk?

Join Me in San Diego

Home Again, Los Angeles, Miami, and Argentina

And Final Thoughts on the Employment Participation Rate

"Sooner or later everyone sits down to a banquet of consequences."

– Robert Louis Stevenson

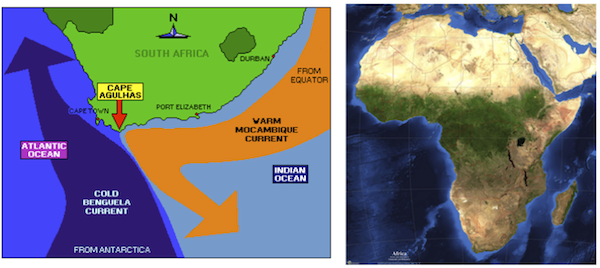

South Africa's Cape of Good Hope is one of the most dangerous stretches of coastline anywhere in the world, where the warm Agulhas Current (also called the Mozambique Current), rushing down from the Indian Ocean, meets the cold Benguela Current, pushing up from Antarctica. The difference in water temperatures alone is a recipe for legendary storms, but the two opposing ocean currents just so happen to converge where the African Continental Shelf drops off into a deep abyss.

So not only do warm and cold pressure systems converge to create raging tempests, but the underwater topography – together with surging waves from the Indian and Atlantic Oceans and fierce winds from the west – frequently gives rise to rogue waves over 80 feet tall, capable of sinking even the largest supertankers and container ships.

Just imagine how terrifying it must have been for the first maritime explorers to brave such dark and dangerous waters. The mind truly boggles at the courage and daring it took.

In a day and age when superstition abounded, unknown and unmapped places were often said to hide the most terrifying beasts of myth and legend; but rounding the Cape must have been a particularly terrifying experience for any uneducated crew. Portuguese legend warned that the long-imprisoned Titan Adamaster, who was said to have been cast into the stone of Capetown's Table Mountain, would never allow a captain and crew to pass the Cape without a fight.

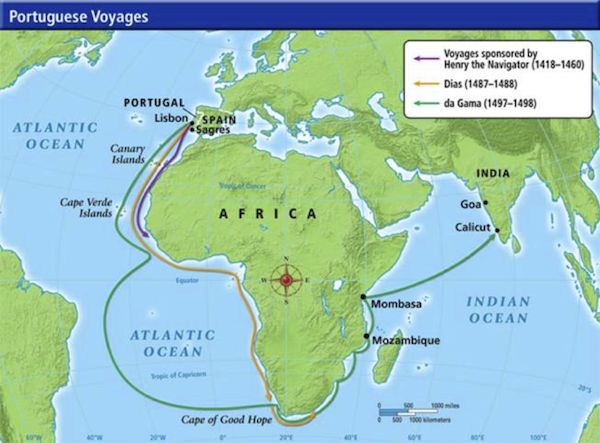

Bartholomew Dias is the first European known to have braved the Cape, in 1488 (four years before Columbus stumbled on the Americas in 1492). Sent by Portuguese King John II to find an ocean route to India, Dias was more than 1,000 miles south of the edge of any known map when a storm blew his ship away from the coastline and out to sea. Little is known of his actual voyage, since the records were later destroyed in a fire, but historians believe Dias must somehow have had knowledge of the southeasterly winds that could blow him around the Cape and against the powerful Agulhas Current (the second fastest ocean current in the world) without crashing him against the rocky coastline. Although Dias survived the storm, successfully rounded the Cape, and unequivocally proved the Indian Ocean could be reached by sailing around the southern tip of Africa, he had not planned for such a long and treacherous journey. With supplies running low and the threat of mutiny in the air, Dias was forced to turn back to Portugal – braving the "Cape of Storms" once more on the way home.

But our story continues (building toward the inevitable, if tenuous, economic connection!). The next great Portuguese explorer to round the recently renamed "Cape of Good Hope" (given that positive moniker by Portuguese King John II, who wanted to encourage sailors to risk the voyage – he was one of the original spin doctors) was Vasco da Gama, who consulted closely with Dias in planning the long, hard voyage from Lisbon to India. With Adamaster's pardon, da Gama successfully sailed around the Cape on the westerly South Atlantic winds Dias had discovered on his first voyage and finally reached Calicut, India, in 1497. Although he eventually died in India, da Gama had finally opened the trade route that European merchants had desperately sought.

Dias was not so lucky. Illustrating the soon to be learned 50-50 odds of challenging the Cape of Storms, Dias did not survive his second voyage. After voyaging to Brazil, the intrepid explorer crossed the South Atlantic Ocean on a follow-up expedition to India – and sailed right into a terrible storm just off the same Cape that had almost claimed his life a decade earlier. Four ships disappeared beneath the waves, and Adamaster had evened the score.

In the years that followed, more than two million Dutch settlers attempted to round the Cape of Good Hope, and more than one million of them fell victim to the high waves, violent storms, and nearly impossible navigating conditions. Naturally, such cataclysmic death and destruction gave rise to another dark myth: the Flying Dutchman.

Now, leaving both historical and supernatural tales aside, let's turn to another CAPE that is deserving of exploration – and that may be signaling danger. As we will see in the pages ahead, buy-and-hold investors are clearly sailing in dangerous waters, where the strong, cold current of deleveraging converges with the warm, fast rush of quantitative easing. Not only does this clash of forces create the potential for epic storms and fateful accidents, it dramatically increases the chances for sudden loss as rogue waves crash unwary investment vehicles against the underwater demographic reef!

Yes, the equity markets are an increasingly treacherous environment, but investors have an opportunity to diversify away from historically expensive equity markets into other asset classes that respond differently to changing economic conditions, and into other countries that may experience very different economic outcomes in the years ahead.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

(Please note that this letter will print rather long as there are more than the usual number of charts.)

The Second Most Expensive Stock Market in the World

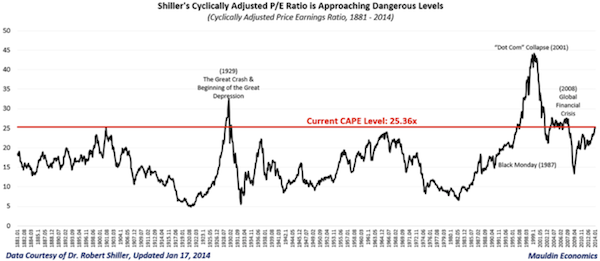

Last week's letter focused on my 2014 outlook for the US stock market and highlighted an important, but controversial, measure for long-term valuations: Robert Shiller's cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE). Unlike the more common trailing 12-month P/E ratio, Shiller's CAPE smooths out the earnings series and helps us avoid what could be false signals by dividing the market's current price by the average inflation-adjusted earnings of the past 10 years. Historically, this range has peaked and given way to major market declines at around 29x on average (26x excluding the dot-com bubble), and it has usually bottomed in the mid-single digits. Except for relatively brief windows during the late 1920s, the late 1990s, and the mid-2000s, Shiller's CAPE ratio has never been as expensive as it is today (see chart below).

As you can see, the S&P 500's high and rising CAPE ratio signals that US stocks are sailing into a well-proven danger zone. Also note that if we get a repeat of the stock market prior to 2007, the market can stay at this elevated range long enough to make investors complacent.

Not only does today's CAPE of 25.4x suggest a seriously overvalued market, but the rapid multiple expansion of the last few years coupled with sluggish earnings growth suggests that this market is also seriously overbought, as I pointed out last week and as we are seeing play out this week. Today's CAPE is just slightly less expensive than the 27x level seen at the October 2007 market peak and modestly below the level seen before the stock market crash in 1929. Although we are nowhere near the all-time "stupid" valuation peak of 43x in March 2000, a powerful narrative drove the markets to clearly unsustainable levels 15 years ago and a powerful narrative is driving markets today. Then it was the myth of dotcom and new tech, and now it is the tale of QE and the Fed.

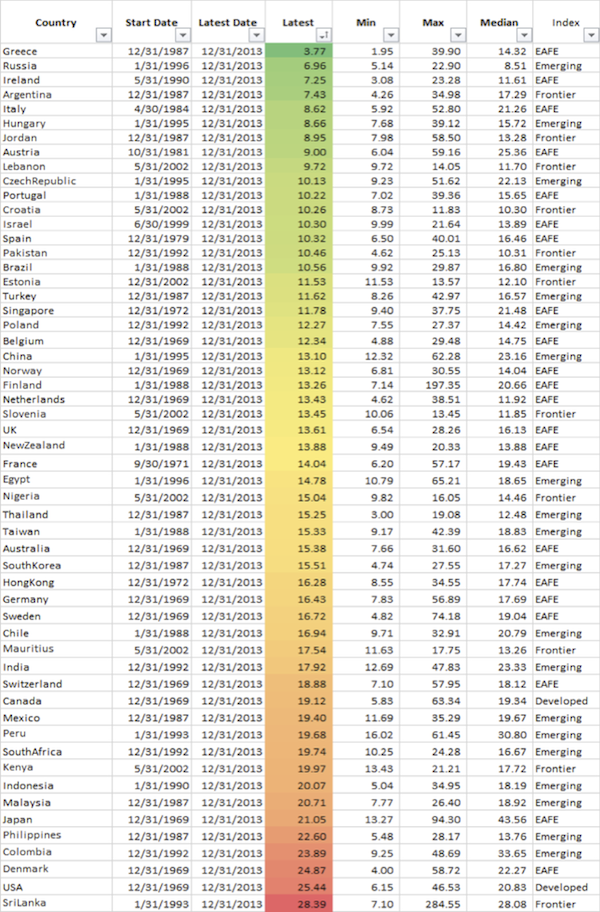

Unfortunately, the outlook for US stocks only looks more daunting when we examine CAPE ratios for foreign equity markets. Mebane Faber, chief investment officer of Cambria Investments and author of The Ivy Portfolio (2009) and Shareholder Yield (2013), regularly posts international CAPE updates to his research blog, The Idea Farm (www.theideafarm.com). Meb was kind enough to let me reprint his year-end 2013 update here.

A quick look reveals that the S&P 500 is the second most expensive stock market in the world today on both an absolute and a relative basis, second only to that of tiny Sri Lanka.

Expanding on recent valuations, Meb's work highlights that the relationship between CAPE valuation and subsequent returns is still very much intact. This next table compares the relative returns of the most expensive and cheapest markets. Study it carefully.

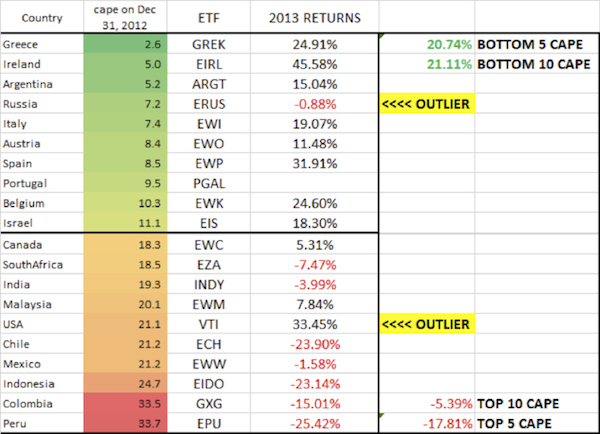

On average, the cheapest 10 markets as 2013 opened returned over 21% last year, while the most expensive 10 markets lost more than 5%. This is just one year, but we would expect to see the same basic relationship over the course of the next decade, if history is a reliable guide. I want to draw your attention to a fascinating observation: look at the outliers.

Russian stocks lost almost 1% in 2013, despite showing the fourth lowest CAPE at the beginning of the year. That's not a huge surprise. Valuations tell us a lot about long-term potential returns but not much about short-term timing. Momentum works until it doesn't.

US stocks tell quite a different story. They returned over 30% last year, despite starting 2013 with the sixth highest CAPE valuation. Rather than reversing course in the face of sluggish earnings growth, CAPE multiples expanded from 21.1x to 25.4x. By comparison, every market that started 2013 with more expensive CAPEs than the US's saw notable reversals of fortune, especially the top three: Peru's CAPE fell from 33.7x to 19.7x; Colombia's fell from 33.5x to 23.9x; and Indonesia's fell from 24.7x to 20.1x.

The impressive thing about US stocks is not simply that positive sentiment and Fed liquidity continued to drive valuations higher, but that the market rallied as much as it did with very modest earnings in the face of historically dangerous valuations. I have said it before, and I will say it again: Sentiment, rather than fundamentals, is driving the US stock market, and sentiment can quickly reverse.

Since we have no idea when the inevitable correction will come, we must expect it at any time. Shiller's CAPE can keep rising longer than any of us expect in the United States, but no one should be surprised if it corrects next week, next month, or next year. My friend, all-star analyst, and Business Insider Editor-In-Chief Henry Blodget makes a compelling point: "Anyone who thinks we need a 'catalyst' for a market crash should brush up on their history… There was no 'catalyst' in 1929. Or 1966. Or 1987. Or 2000. Or 2008…"

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

So let's take Henry's advice and brush up on our history…

Average 60/40-type investors unknowingly concentrate over 90% of their portfolio risk in stocks and typically allocate over 80% of their stock portfolio to their home market. Consequently, most US-based investors are incredibly exposed to US equities and could suffer life-altering losses in the event of 1929- or 1987-style stock market crash. No one believed such an event was possible back then or in 2000 or 2006.

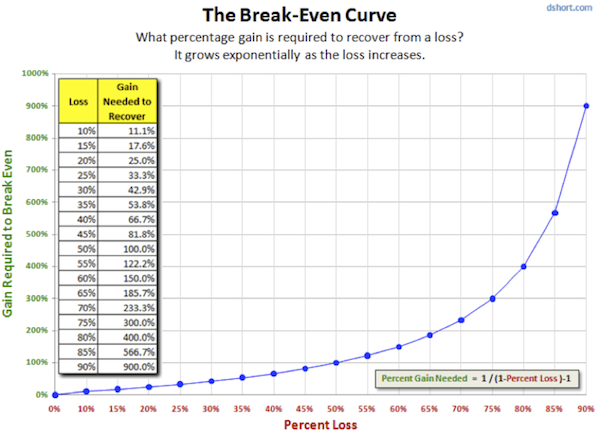

As you can see in chart above, large losses are exponentially more damaging than small losses. It takes only an 11% return to recover from a 10% drawdown and a 25% return to recover from a 20% drawdown. These kinds of losses are manageable for disciplined, long-term investors; but recovery from larger losses is far more demanding. For example, it takes a 100% return just to recover from a 50% drawdown and a 300% return to recover from a 75% loss. The numbers can get out of hand in a hurry, and most investors have no idea how much of their future depends on the health of just one market, within just one asset class.

With the average investor's total lack of diversification in mind, I want to spend a few minutes exploring a seeming contradiction in the markets. This week I was in Canada at three CFA forecast dinners and heard my fellow speakers generally forecast much higher interest rates for the US bond market in particular and the world in general. And everyone was bullish. (The consensus forecast for the S&P 500 from the college student contingent at the CFA dinner in Regina was 2300. You have to admire youthful exuberance!)

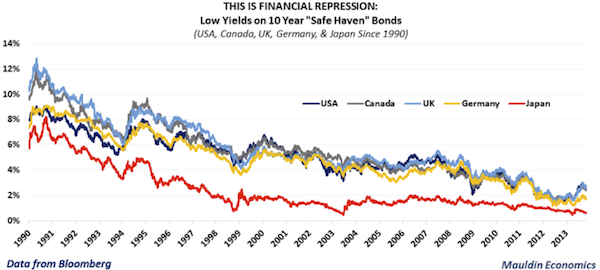

Look at the chart below. Note that even with the recent rise in 10-year bond yields, those yields are still historically low, punishing savers and distorting comparable stock market valuations.

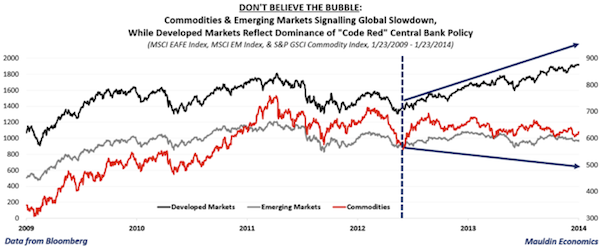

Yet, even as low interest rates drive a reach for yield in the US and other developed markets, commodities and emerging markets may be signaling a global slowdown. In fact, most of the predictions for global growth this year make heavy assumptions that the developed markets will pick up the pace.

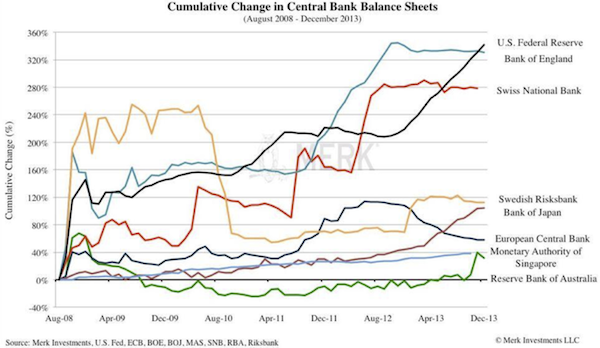

The question on everybody's mind is, how much of the rise in market valuations has been due to the expansion of central bank balance sheets in the developed world? Rather than seeing inflation in the prices of things we buy, are we seeing inflation in assets? (And more on inflation in a minute.)

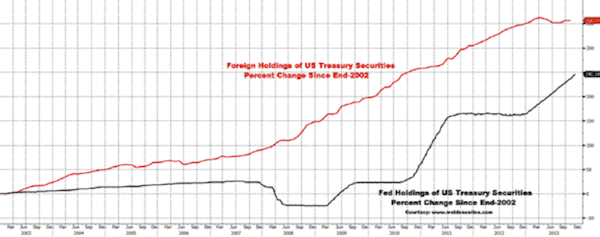

Greg Weldon highlighted the problem extremely well in last week's Outside the Box. If you haven't read it, you should. Among other things, he points out that the Federal Reserve's holdings of US treasuries have been rising dramatically while foreign holdings have gone flat. The central banks of the world are not aggressively selling US treasuries, but they are either directly saying or clearly demonstrating that their appetite to increase their holdings of US treasuries is sated.

Greg asked the question, "As the Federal Reserve begins to taper, who will buy the almost $4 trillion of US treasuries that will have to be sold this year?" Much of it will be simply rolled over, of course, but there will still be $500 billion at a minimum (depending on the extra losses from Obamacare, which are beginning to mount) of new money that will have to be found. Greg thinks the natural direction for interest rates is up, and almost everyone seems to agree.

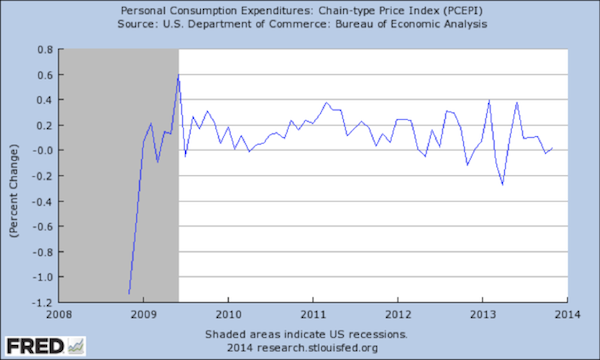

The problem is that interest rates generally have a very tight relationship with inflation. I get that measuring inflation is subjective, but by almost any measure inflation is extraordinarily low given the amount of money that central banks have injected into the economy. We are in a deflationary, deleveraging world where the bias to inflation is down. From one perspective, it is only the massive amount of central bank printing that has been able to give us even the modest inflation we have today. And by the Federal Reserve's preferred inflation model, inflation is basically zero, as the chart below shows.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

Even if you use the more standard CPI inflation, the year-over-year increase has fallen to 1.5%; and given that the direction of gasoline prices is probably down, the bias for the future is even lower.

For interest rates to rise much from here, either inflation needs to pick up, or there must be a disconnect between the normal relationship between inflation and interest rates. This is just one of the reasons that analysts like Lacy Hunt continue to believe that the longer-term bias for interest rates is down.

So, an actual forecast? With the caveat that I don't have a real clue but am just trying to make an educated guess? Unless there is something that spikes the price of energy, inflation will stay low, and I think that's going to be an anchor on the rise in interest rates. Which means that yields will stay down, and the reach for yield that has been so evident in the markets for the past few years will continue to be a dominant factor. That means credit spreads will tighten even further, though that still wouldn't take them outside historical boundaries.

And those factors give the longer-term direction of the market an upward bias – after we have a correction sometime this year. Are we in the midst of that correction now? Possibly.

Thirty years ago one of my mentors gave me a rule: Mr. Market is a vicious sadist. He will do whatever it takes to create the greatest amount of pain for the largest number of investors. The way that might happen this time around is that we could see a few real corrections, with the market climbing back to ever-new highs after each one, and finally luring in everyone who will be fool enough to reach for that last bit of yield, before there is a really breathtaking correction. I wrote 14 years ago, at the beginning of what I predicted would be a secular bear market, that there are typically three major corrections before we get down to low valuations. We have had two this time around, and I think Mr. Market is setting us up for a third somewhere down the line. At that point valuations all over the world will drop, and it will be time to start talking about a long-term secular bull market.

For now, if you want to play the markets, you might want to look outside of the United States for some potential and pay attention to those markets that are already at low relative valuations. Remember that all markets are going to go down in the next true bear market, but some will go down less than others. Diversification and hedging are the order of the day.

We need to be paying attention to the European bank stress tests, how China deals with its burgeoning bank debt crisis, how the market responds to the actions of the French government to deal with its budget deficit.

But most of all, we need to stay laser-focused on whether tapering by the Fed will have an effect on emerging markets or on US interest rates. This could be the trigger for some very nasty market action. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, reporting from the World Economic Forum in Davos, had a piece on this topic just yesterday.

We have never been in a situation where the central bank that controls the world's reserve currency has injected trillions of dollars into the system and then decided (and undecided and then redecided) to reduce those injections. Has the world grown addicted to its QE fix? Or will withdrawal be a nonevent, as many are predicting? I truly hope that the research which suggests that quantitative easing had no real positive additive effect on the markets means that the oh-so-gradual tapering of QE won't really be noticed.

The simple answer is that no one knows. We are in completely unknown territory, with the FOMC conducting experimental surgery on our economic body without benefit of anesthesia. At the very least, the Fed's new direction has the potential to increase volatility globally.

At the end of the day I agree with my friend Ben Hunt, who is quite concerned that the narrative surrounding the Federal Reserve could change in the course of tapering. The Fed has been given the lion's share of the credit for the positive economic results we've had coming out of the Great Recession. What happens when that story – what Ben calls the Fed's narrative – changes? He sent me this note yesterday:

For 20+ years there has been a coherent growth story around Emerging Markets (EM), where the label "Emerging Market" had real meaning within a common knowledge perspective. Today … not so much. Today the story is that it was easy money from the Fed that drove global growth, EM or otherwise. Today the story is that Emerging Markets are just the levered beneficiaries or victims of Fed monetary policy, no different than anyone else….

I'm not asking whether the growth rate in this Emerging Market country or that EM country will meet expectations, or whether the currency in this EM country or that EM country will come under more or less pressure. I'm asking if the WHY of EM growth and currency valuation has changed. The WHY is the dominant Narrative of a market, the set of tectonic plates on which investment terra firma rests. When any WHY is questioned and challenged – as it certainly is in the case of EM markets today – you get a tremor. But if the WHY changes you get an earthquake.

What are the investments that such an earthquake would challenge? You don't want to be short the yen if this earthquake hits. You don't want to be long growth or anything that's geared to global growth, like energy or commodities. You don't want to be overweight equities and underweight bonds. You don't want to be overweight Europe. There ... did I cover one of your favorite investment themes? Bet I did. You can run from EM's with US equities, but with S&P 500 earnings driven by non-US revenues, you cannot hide. If you think that your dividend-paying large-cap US equities are immune to what happens in China and Brazil and Turkey … well, good luck with that. My point is not to sell everything and run for the hills. My point is that your risk antennae should be quivering, too.

What Ben is describing is what will happen in the next major bear market. Almost no one thinks that will happen this year. Do you worry when other people are worried? Is the fact that people are seemingly not worried a reason to be concerned? As valuations around the world move up, investors should become more cautious, not less.

I started this letter talking about the Cape of Good Hope, one of the most treacherous stretches of ocean on Earth. And then I managed to segue more or less gracefully (I hope!) into a discussion of CAPE valuations. I don't think that people who are enthusiastic about this market understand they are getting ready to sail around the investment equivalent of the Cape of Good Hope. Hope, as we well know, is not an investment strategy. The next leg of this journey will require all the planning, preparation, and caution that you can muster. Don't look now, but the Titan Adamaster is a pussycat compared to Mr. Market.

Before I close today, let me invite you to join me in San Diego, May 13-16, for my annual Strategic Investment Conference, cohosted with my partners Altegris Investments. Also joining us (so far) will be Niall Ferguson, Kyle Bass, Ian Bremmer, David Rosenberg, Dr. Lacy Hunt, Dylan Grice, David Rosenberg, David Zervos, Rich Yamarone, my Code Red coauthor Jonathan Tepper, Jeff Gundlach, and Paul McCulley, with a few more surprise names waiting to confirm. Nothing but headliners, one after the other.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

When I first broached the idea of our conference to Jon Sundt, the founder of cosponsor Altegris, the one rule I had was that I wanted the conference to be one I would want to attend. The usual conference boasts a few headliners, and then the sponsors fill out the lineup. I wanted to do a conference where no speaker could buy his way onto the platform. That means we often lose money on the conference (hard as that may be to imagine, at the price, I acknowledge); however, the purpose is not to make money but to learn with – and maybe have some fun with – great people. We do put on a great show, and my partners make sure it is run well. But the best part will be your fellow attendees. A lot of long-term friendships are forged at this conference. You can learn more and sign up at http://www.altegris.com/sic.

Home Again, Los Angeles, Miami, and Argentina

I arrived home yesterday after a rather tiring four-day, three-city tour of Western Canada. But now I look at the calendar and find that I may be home for nearly four weeks! I can't remember the last time I was home for four weeks running. Something will probably come up, but until it does I intend to be far more regular with the gym and yoga and to reestablish something that resembles a routine in my life.

At the end of the month I go to Los Angeles and then cross the country to Miami. It looks like I may fit in another quick trip here or there, but I want to invite you to join me in the middle of March for an experience of a lifetime in Argentina's emerging wine country. A couple of years ago I was invited to visit La Estancia de Cafayate, a unique lifestyle and sporting estate in the up-and-coming wine-producing town of Cafayate in Northwest Argentina. I enjoyed the place so much that I returned again the following year, and I am doing so again March 17-22 in order to participate in the annual Harvest Celebration there.

As a Mauldin Economics subscriber, you are cordially invited to join in the fun in the sun, play some golf, hang out at the world-class spa (an hour-long, fabulous massage works out to about $20), enjoy wine tastings in the town's many small bodegas, rub elbows with interesting folks at gala dinners and social events, ride horses, tour the area, and generally soak in the rich culture of the Argentine outback. Given the somewhat chaotic nature of Argentina today, the country is on sale, and everything is cheap. It is a fabulous place to go for those seeking a "value vacation." And Cafayate is in one of the most beautiful settings anywhere in the world. The drive through the canyon (Quebrada del Rio de las Conchas) to get there is simply breathtaking.

In addition, as icing on the cake, there will be a half-day conference featuring yours truly; Bill Bonner, the chairman of Agora Financial; Doug Casey, the original international man; Claudio Maulhardt, a top-performing emerging markets fund manager; Frank Trotter, president of EverBank Direct; and Dr. Ted Harrison, a life extension expert.

The cost of the event is just $350, a real bargain. Which probably explains why the Harvest Celebration at La Estancia de Cafayate always sells out fast – you'll want to write for more information today. To learn more, drop a line to Chris Leverich, grapevine@LaEst.com.

And Final Thoughts on the Employment Participation Rate

On a final final note, I just picked up an odd factoid from Derek Burleton, vice-president and deputy chief economist of TD Bank Financial Group.

They did an analysis of the precipitously falling US employment participation rate. If Canada had the same participation rate as the US, their unemployment level would be in the 2% range. Now, as I travel around Canada (and with the trip to Regina, Saskatchewan, I have now been in all of the border provinces) I generally don't see much of a difference in the "feel" of the place as compared to the US, aside from the normal regional quirks you experience anywhere in the Western world. In other words, it mostly feels like home, and other than the weather, it seems like an all-around great place to live.

For there to be such a significant difference in our labor participation rates tells me that something is happening in the US that is not just a seasonal factor or something that will go away when the economy finally returns to a normal growth trajectory somewhere in the future. I am concerned that the difference is systemic in nature, and that makes me uncomfortable. It doesn't bode well for the return of animal spirits and growth.

And on that somber note, I will hit the send button. Have a great week.

Your off to the gym again analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Put Mauldin Economics to work in your portfolio. Your financial journey is unique, and so are your needs. That's why we suggest the following options to suit your preferences:

-

John’s curated thoughts: John Mauldin and editor Patrick Watson share the best research notes and reports of the week, along with a summary of key takeaways. In a world awash with information, John and Patrick help you find the most important insights of the week, from our network of economists and analysts. Read by over 7,500 members. See the full details here.

-

Income investing: Grow your income portfolio with our dividend investing research service, Yield Shark. Dividend analyst Kelly Green guides readers to income investments with clear suggestions and a portfolio of steady dividend payers. Click here to learn more about Yield Shark.

-

Invest in longevity: Transformative Age delivers proven ways to extend your healthy lifespan, and helps you invest in the world’s most cutting-edge health and biotech companies. See more here.

-

Macro investing: Our flagship investment research service is led by Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino. His thematic approach to investing gives you a portfolio that will benefit from the economy’s most exciting trends—before they are well known. Go here to learn more about Macro Advantage.

Read important disclosures here.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

Tags

Did someone forward this article to you?

Click here to get Thoughts from the Frontline in your inbox every Saturday.

John Mauldin

John Mauldin