The Likelihood of a Crash

-

Jared Dillian

Jared Dillian

- |

- October 26, 2023

- |

- Comments

My friend Michael Gayed is calling for a crash. I’d include the tweet here, but he swears all the time. It doesn’t bother me, but he’s not everyone’s cup of tea.

I’ve been doing this for a while, and I’ve seen people call for crashes before. The funny thing is, I kinda agree this time.

Though you will never see me “call” for a crash, I will say when the probability of one is elevated. A few people called the crash of 1987 and positioned themselves for it. They are legends. A crash is not this random, exogenous thing that randomly happens. There are events that lead up to it.

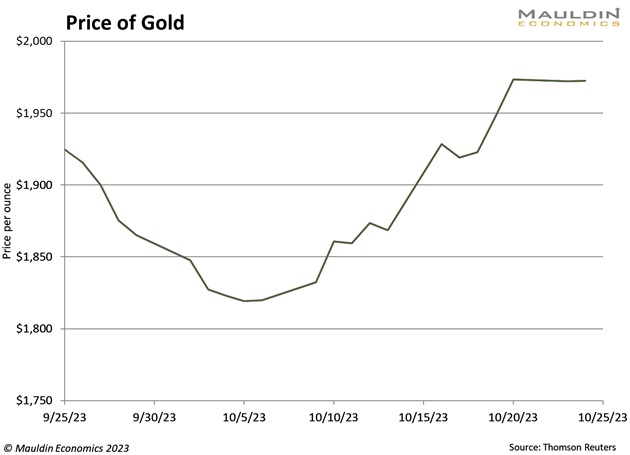

In this case, the war in Gaza, but also relentless dollar strength, interest rates ripping higher, and out-of-control government spending. Even the casual observer can see there is stress in the markets. Positioning is at extreme levels. Gold is ripping higher.

None of this bodes well for stocks.

Here’s a headline from Bloomberg: “Paul Singer Says World More Perilous Than Markets Pricing In.” Singer and I agree on that, for sure. With all that’s going on in the world, it’s hard to believe that we’re at 4,200+ on the S&P 500, a full 20% off the lows, and not far off the highs. A crash certainly could happen, and nobody is positioned for it. Nobody is psychologically prepared for it.

The Definition of a Crash

What is the definition of a crash? I would say when the market goes down more than 10% in a single day. In 1987, the market went down almost 25% in a single day. The crash of 1929 was actually two crashes on consecutive days, 12% and 13%. The Flash Crash in 2011 was about 10%.

To my knowledge, we haven’t had many others aside from some really volatile days during the financial crisis and the pandemic. If we had a crash of 10%, that would be 420 points in the S&P 500. That would certainly get people’s attention.

As I write, Israel has not yet commenced its ground invasion of Gaza. If it does, and if it goes pear-shaped, that would be a potential catalyst for a crash. There are many.

So, the antidote here is to buy protection. In index options, it is not that expensive… yet. It has certainly been cheaper. It might not be a bad idea to waste 1%–2% of your performance on protection—you know, just in case. You can also get upside exposure to bonds, upside exposure to gold, upside exposure to oil, and upside exposure to volatility.

Insurance costs money. But I’m always struck by how many people are willing to insure their car and their house but not their portfolio, which is orders of magnitude bigger. Of course, having insurance on your car is a precondition for driving a car, and having insurance on your house is a precondition for having a mortgage. And, for sure, there would be some people who would elect to not have insurance if it was not compulsory. But you should get insurance—it is not a zero-sum game. I had insured my portfolio before the pandemic crash, which offset most of the losses. I felt pretty smug about that.

Worst-case scenario, you waste a little money in option premiums, and the stock market motors higher. Definitely not a bad outcome.

When Paul Singer says that the markets are not pricing in terrible peril, all you have to do is look at the VIX, which is below 20. Arguably, it should be above 30. This is an obvious mispricing, and maybe someday we’ll look back at what is an obvious mispricing.

Not to Be Confused with Bearishness

If you’ve been reading me for a while, you know that I’m not monotonically bearish, that I don’t go around calling crashes, and I don’t say splashy things for clicks. All I’m saying is that the probability of a crash has gone from 0% to 5%.

I don’t believe in market determinism. I like to look at things probabilistically instead. Five percent is big enough for me to take action. I want to be positively exposed to gains in disorder. If you are negatively exposed to gains in disorder, you will be suffering along with everyone else if the worst happens. If the worst happens, I want to be safe and secure. Best-case scenario: I want to win.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Thursday! Read our privacy policy here.

Jared Dillian, MFA

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com

Jared Dillian

Jared Dillian