Quick question...

Interested in more?

You can join Jared Dillian's Bond Masterclass right now (and save 50% through October 3 only)

You can join Jared Dillian's Bond Masterclass right now (and save 50% through October 3 only)

Few things in investing are more misunderstood and unappreciated than bonds. Going on the results of my bond survey, they’re boring. But also risky. They’re simple. But also super complicated... Bonds have a serious PR problem. The truth is that bonds are sometimes all of those things.

In this special series of The 10th Man, my goal is to begin to demystify the opaque world of bond investing so that you have a genuine understanding of bonds, and you can use them effectively. I guarantee that genuine understanding will put you leagues ahead of about 80% of individual investors out there. New issues added here every Thursday.

I should download the Family Feud wrong answer noise. It might come in handy in the future.

You guys...

Thousands of you took my bond survey (thank you for doing that).

Many of you have been very naughty.

45% of you said that 0-20% of your portfolio is invested in bonds.

51% said that if you were starting a portfolio from scratch, you would keep the same allocation to bonds.

Naughty! People just love those sweet, sweet stocks and those 10 years of historical returns. Apparently, few of my subscribers are over the age of 11. If you were, you might remember a period that was terrible for stocks and pretty darn good for bonds.

I’ve talked several times about how the optimal portfolio has as much as 65% bonds, versus a 35% allocation to stocks. Yes, most of the time that portfolio has a lower return. It also has a lower volatility, which is the point. Volatility causes people—even super smart people—to make stupid investment decisions.

You have heard me say that before. Clearly, a large percentage of you did not listen. Maybe I can tell you a few more things that will spark your imagination.

You might ask yourself: “Why the hell should I invest in bonds now? Interest rates are so low!”

Fair point. It is not much fun being an income investor when 10-year Treasurys only yield 2%. And the conventional wisdom is that most people invest in bonds for income.

There is, however, another reason you can invest in bonds with low interest rates. For the price appreciation!

If interest rates go even lower, these bonds will go up a lot.

You might say: “How can interest rates go any lower? They are already almost zero.”

Well, they can go to zero, and they can go lower than that, too. It might even happen here in the United States.

If that comes to pass, then the prices of these bonds are literally going to skyrocket—because of convexity.

I’m not going to do a whole finance lecture on bond convexity today, but just know that convexity is curvature. Bond prices will go up a lot faster than they come down.

Of course, this is not the sign of a healthy bond market. The bond market is heavily manipulated by central banks and governments. So getting back to the Trump Train article from a few weeks ago—do you want to get steamrolled by this, or do you want to play along?

No policymaker in the world—literally none—wants higher interest rates. There are still people out there trying to short bonds, fighting the last war.

I have written in The Daily Dirtnap (you may want to consider a subscription) that there is a nonzero probability that the bond market will turn into a full-fledged bubble, just like dot-com stocks in 2000. Maybe you think it already is a bubble. You ain’t seen nothing yet!

I have just listed a bunch of reasons why one should invest in bonds, but for now, you shouldn’t care about anything I said. All you should care about is a bond’s contribution to portfolio risk.

All anyone cares about these days are returns. The thinking is that you need 8% (or 10, or 12%) returns to save for retirement. News flash: if you sustain a 50% drawdown and panic into a diaper, the returns stop compounding. You would have been much better off with a diversified portfolio of stocks, bonds, and a little bit of commodities.

I have heard stories about the robo-advisors putting people into 80+% stock allocations even when they list their risk preferences as “conservative.” For a lot of financial advisors, conservative just means “safer stocks,” not “less stocks.”

One example—a young reader was figuring out his 401K allocation, and the target retirement fund that was being offered was a 2060 target retirement fund... which had 90% stocks and 10% bonds. I told him to look at the 2030 target retirement fund, even though he is in his early 20s. He said the allocation wasn’t much better.

The world is gorked up on stocks.

The optimal portfolio (based on the Sharpe Ratio) is the 35/65 portfolio. 35% stocks, 65% bonds. That’s for all ages.

I have tested this. Remember when the S&P 500 Index dropped almost 60% during the financial crisis? That’s a 50 to 100 year event, and the worst drawdown you would have taken with this portfolio—the absolute worst—is 25%. Nobody can survive a 60% drawdown, and dollar-cost average all the way down. Unless you’re in a coma.

I had suspected people’s reticence to invest in bonds or bond funds is rooted in a lack of understanding of how they work. The results of the bond survey back that theory up.

You don’t invest in what you don’t understand. Okay, people invest in what they don’t understand all the time, usually with disastrous results. This time, let’s do it right.

In the coming weeks in The 10th Man, we’re going to talk about bonds: what’s happening right now, some of the most misunderstood concepts around them, and of course—the questions and concerns you shared in my bond survey (there were a lot).

I am not being hyperbolic when I say that the range of questions you asked was spectacularly broad. The multiple-choice answers were all over the map, too.

Anyway, one of my favorite comments so far was: “Each time I learn about bonds, I understand what the speaker is saying, but only until he stops talking.”

Challenge accepted.

Jared Dillian

Interest rates are currently low.

That was by far the biggest concern mentioned in the bond survey. People are drowning in worry about low interest rates and their effect on bonds. So let’s address that.

Saying interest rates are currently low is another way of saying that bonds are expensive—which makes people not want to invest in bonds. Fair enough.

Stocks are also expensive—but you invest in those!

So why are you willing to invest in expensive stocks, but not in expensive bonds?

What are your alternatives?

Cash

Commodities

Real Estate

Collectibles

None of those look appealing right now.

Here’s the reality of the situation. If you have capital to spare, you—as an individual investor—are going to end up putting most of it in the stock market and the bond market, because those are the deepest, most liquid capital markets.

I suppose you could go on strike, and keep it all in cash. One day that might make sense.

I suppose you could go on strike, and keep it all in commodities, but they are not cheap to carry.

Or real estate, but that has special risks.

Stocks and bonds—those are your choices.

So I ask you again: why are you willing to invest in expensive stocks, but not expensive bonds?

Yes, it would be nice if stocks and bonds were cheaper. But that is not the world we currently live in.

The reality is that you need both stocks and bonds to have a diversified portfolio. No matter how expensive they get.

Stocks and (most) bonds behave differently. Sometimes stocks go up and bonds go down, and vice versa. This smooths out the volatility in your portfolio.

The stock market gets volatile sometimes. I wouldn’t want my entire nest egg in an asset class that is ripping around 7% a day. The bond market is occasionally volatile, but nowhere near as volatile as stocks.

And having bonds in your portfolio does more than reduce the volatility—it also improves the risk characteristics of your portfolio. It makes your portfolio more efficient in its use of risk.

You can compare one portfolio against another portfolio to determine which one is better. And a portfolio that is mostly bonds has the most efficient use of risk, which makes it better. What I mean by that is you will have a better rate of return per unit of risk.

It has zero to do with the actual level of interest rates. Interest rates could be negative, and you would still want bonds in your portfolio, for risk reasons.

This is called diversification. Diversification is the idea that adding something “bad” to your portfolio can actually make it good. Anyone who has done any academic work on portfolio management (including CFAs) know this is true.

Once more for those in the back, low interest rates do not mean you should not own bonds.

Some people get all huffy about low/negative interest rates. Negative interest rates are socialism! Negative interest rates are manipulation!

Maybe not.

The classical definition of interest rates is the price of money that balances the supply and demand for loanable funds.

There is a huge supply of loanable funds out there. There is a giant wall of money that needs to find a home. There is so much money that we can’t even find places for it.

Is that a consequence of central banking? Maybe.

Do you want to fight it? Probably not.

If you own bonds that yield 2% and inflation is 3%, you will have a real return of -1%. This is an indisputable fact. Inflation hurts bonds.

Core PCE (the personal consumption expenditures price index) recently came in at 1.6%. It seems like we should be having more inflation, but we aren’t. I personally think inflation will go up! But it isn’t going up much now.

Even if it does, what are your options? Stocks are supposed to keep up with inflation, but what if they don’t?

Actually, your options in a high-inflation environment are commodities and real estate, and there might come a point in time where inflation ramps and you want to be in commodities and real estate (like the late 1970s), but that is a very long way off.

So we are back to stocks and bonds, both of which are overvalued, and both of which you have to own. There is a chance that returns on both stocks and bonds will be low. But if you want to be invested, you have to own both of them!

Finally—and a lot of people are missing this—there is the very real possibility that bonds outperform stocks over the next few years.

Last week I talked about convexity and the possibility that bonds will go parabolic.

If you know anything from reading The 10th Man over the years, you know that not only do stupid things sometimes get more stupid, stupid things usually get more stupid.

Negative rates may be a bubble, but bubbles can last for years.?

Stan Druckenmiller (if my memory serves me correctly) was forced to retire and convert to a family office when he lost a fight with the bond market. And that was when yields were a lot higher!

I’m not pushing anything radical here. All I am saying is this: if you are an ordinary investor, and not a macro hedge fund manager, you should have a mix of both stocks and bonds, and probably more bonds than you think. That’s it.

We need less of this...

“My sister’s financial advisor thinks she should be 100% invested in tech stocks like Facebook, Amazon, etc. and [that] she can withdraw 7% every year and grow her account. My sister is 77 and has no source of income beyond Social Security and is in assisted living. Where did ‘know your customer’ go?”

...And more of this...

“[Bonds’] low income is a bitter pill to swallow when the stock market is soaring, but I can sleep at night (as opposed to 2008 - 2009, when I lost half my savings).”

(Both of these comments are from readers.)

See you next week.

The first thing I read about investing wasn’t actually a book. It was a pamphlet that I got somewhere, 23 years ago.

The pamphlet said you should invest in bonds as well as stocks. It said bonds went up when interest rates went down, and vice versa. It didn’t go into any more detail.

Well, I did what the pamphlet said, even though I had no idea what the hell I was doing, and wouldn’t figure out for a few more years why it was a good idea.

I suspect a lot of people don’t take that advice on diversification, simply because they don’t know what the hell they are doing.

I taught finance at Coastal Carolina University for five years. Four years in the MBA program. In the MBA program, I used to teach a course called Financial Institutions and Markets, which I loved.

After the semester, one of the students came up to me and said he expected to learn all about how to trade stocks in the class. He thought the whole class would be about the stock market, when in fact, about 85% of the class ended up being about the bond market.

I told him, “Yeah, the stock market is quite a bit smaller, and frankly, it isn’t that important. People focus on it because stocks are easy to understand. But if you want to understand how the world works, you need to understand bonds.”

He was a nontraditional student, and the manager of the largest strip club in town, so I’m not sure what he did with his bond knowledge. But at least there is one more financially literate person out there.

Anyway, it is impossible to understand how the world works in one issue, but we are getting there week by week.

Today, we’re going to take a quick look at a few different types of bonds, because I got hundreds of questions in the survey asking stuff like: “Should I invest in munis? Why should I invest in Treasurys over corporate bonds? What are the pros and cons of different bonds?”

Treasury bonds are relatively straightforward (probably why 34% of bond investors in the survey said they were mostly invested in them).

The government borrows money from the public in the form of bills, notes, and bonds. For years, these bonds were considered to be “risk-free,” though you could have a much longer discussion on that now.

The interest rates on Treasury bonds are pretty much the benchmark for every other interest rate in the world, including your mortgage. They also give you a pretty good indication as to which way the economy is going, if you know how to make sense of the numbers.

Buying a Treasury bond is a pure play on the direction of interest rates. If you think interest rates are going down, you would buy Treasurys. Which is a bit ghoulish, because if interest rates go down it is supposed to mean bad things are happening.

I think you have just figured out one reason you need bonds in your portfolio.

Corporate bonds are debt issued by corporations. Also straightforward. But corporates are considered to be riskier than the government, so their interest rates should be higher (because you should be rewarded for taking on more risk), and they generally are. The difference between treasury and corporate interest rates is called a spread, and trading corporate bonds is often called spread trading.

Corporate bonds are rated by rating agencies, and the higher-rated ones are called investment grade, and the lower-rated ones are called high yield. High yield bonds have higher yields, as advertised, but are riskier and more likely to default. Investment grade bonds don’t default very often, but people have become concerned recently about the perceived riskiness of lower-quality investment grade corporate bonds.

From the survey: 26% of you who are invested in bonds are holding investment grade corporate bonds, versus just 4% holding high yield bonds. If you’re among the 26%, now is a good time to check how much of your holdings are lower-quality investment grade (BBB).

Mortgage-backed securities are pools of mortgages on residential real estate. As you probably know by now, your mortgage has been securitized into a pool which can be bought by investors. Your principal and interest payments are passed through the bond to the investor (MBS are frequently called pass-thrus).

I would need more time to explain exactly how MBS behave, but just know that when interest rates go down, the value of MBS don’t go up very much... yet when interest rates go up, the value of MBS go down a lot. Kind of the worst of both worlds. Why buy these bonds? They yield a bit more, because of the prepayment option, which has to do with the refinanceability of your mortgage.

Sovereign/International bonds are bonds issued by foreign countries or foreign corporations. Some of them are denominated in US dollars, and some of them aren’t. The ones that are denominated in local currency obviously give you exposure to that currency. The currency exposure is generally the overriding concern with these bonds.

Sovereign bonds are neat because to analyze them, you generally need to analyze political risk, and you have to be up on politics in foreign countries. That’s fun, but not necessarily a great idea.

Sovereign bonds are generally treated as corporate bonds—they trade at a spread to US Treasurys.

By the way, just 3% of those of you who are invested in bonds are invested in international bonds, according to the bond survey. That may or may not be a good thing, depending on where you go in the world.

Municipal bonds are bonds issued by state and local governments. Municipal bonds have had a historic rally recently.

The interest on municipal bonds is exempt from federal taxation, and sometimes state and local taxes, which makes them appealing to investors in high tax brackets. If you are in a low tax bracket, munis are generally a waste of time, because the yields are so low.

Some municipalities are in terrible financial shape, which sometimes keeps people from investing in their bonds, but they rarely default, because, well, you can always raise taxes.

There are also tens of thousands of issuers and financial data is typically not available, so the market is famously murky. Also, the Puerto Rico municipal bankruptcy is working its way through the court system and might be setting some not-nice precedents for muni bond investors.

The thing that sucks about investing is that you have a full time job where you work 8 hours a day, but you have to somehow also make smart investing decisions.

The reality is that your financial education is your own responsibility, so you have to put in additional work to learn about the financial markets. And the knowledge barrier to entry with bonds is a bit higher than with stocks. There is quite a lot to learn.

I guess you could just cede control to some mook and pay the mook 1.25%. Not to demean the advisory industry, but financial advisors have a powerful incentive to get you to take as much risk as possible—clients are angriest when they underperform the market.

If the mook option doesn’t sound like a good idea to you, see you next week.

Jared Dillian

First, please do me a favor—I would love it if you would follow me on Twitter.

By this point, you have probably heard that $15 trillion of bonds are trading with negative yields, which represents 25% of all sovereign bonds outstanding. Lots of people are indignant about this—but it’s no use getting mad at the market.

Lots of people say it doesn’t make sense. It makes sense to me, and to a few other people. If you see something in the market that doesn’t make sense, it’s usually best to stay away, rather than picking a fight with it.

We’re not in uncharted territory here. Let’s do a market psychology exercise.

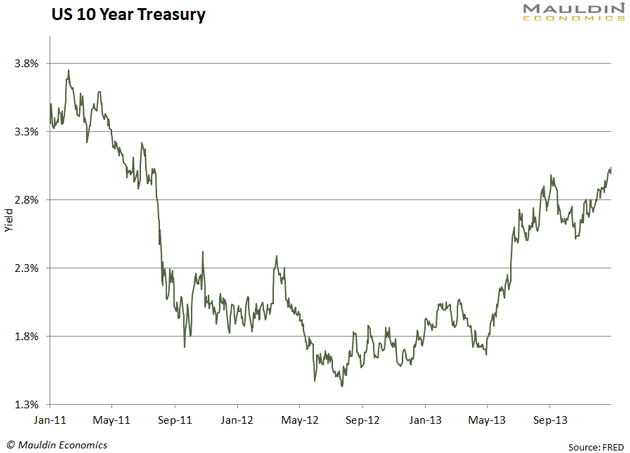

Back in 2012, ten-year yields were actually lower:

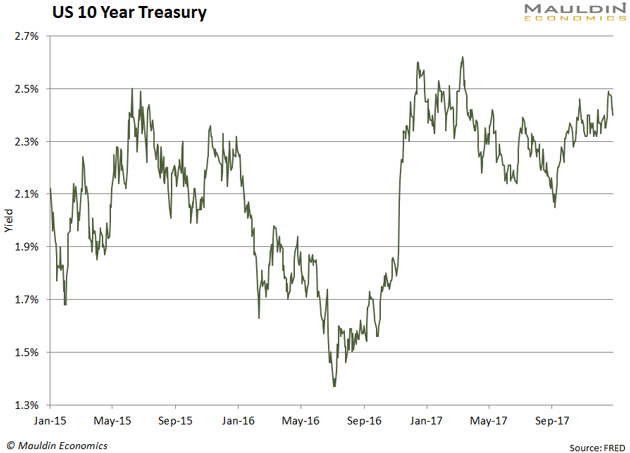

And again in 2016:

Both of those times (and I remember this quite clearly), people were bullish on bonds and said that yields were going lower. Instead, they rocketed higher. They said that the deflation/disinflation that we were experiencing was unstoppable, and a whole bunch of other stuff, that turned out not to happen.

In 2016 I presented a short bond thesis at a conference and I practically got hounded off the stage. Nobody remembers this, but everyone was really bullish on bonds back then. It was actually kind of a weird situation. The organizers of the conference avoided me after that, like I was radioactive.

Now practically nobody is bullish! Why is that? I suppose the inflation picture is markedly different—we have tariffs and there are wage pressures and such—but I don’t think that’s what this is about.

My thesis, which I have carried around for 20 years: when everyone believes something, it is usually wrong.

What does everyone believe right now? That negative yields are unsustainable.

Maybe that is true. Maybe not.

You can have a bubble in any asset class, from little stuffed animals to lines of computer code. Why not bonds?

The bitcoin bubble burst when there were more Coinbase accounts than Schwab accounts, and there was a bitcoin rapper in the New York Times. We don’t have any bond rappers yet, so I’d say the bull market has a ways to go.

George Soros always said that if he saw a bubble forming he would get in there and try to make it bigger—which is pretty much the opposite of what everyone does.

What everyone does, is goes on Twitter to complain about it. It’s not just Twitter—negative yields was probably the biggest concern you guys listed in the bond survey.

Right now, people don’t believe in the trade, or understand it. This is going to continue until they do understand it.

There are also fundamental reasons which are plainly obvious—bad demographics and a savings glut, which creates huge demand for safer assets like bonds, pushing down yields. Both of those things were cited the last two times around (2012 and 2016), but not this time.

My opinion: smart people (including the owner of this website) predicted debt and deflation years ago. You know how it happens. Gradually, then suddenly.

Anyway, I can’t do one scroll through Twitter without someone freaking out about negative interest rates. Turn on the internet and see. But what if negative interest rates… are normal? What if they make sense?

Ask this question around certain people and they completely lose their minds. The last time I saw people get this indignant about a trade, it was… Beyond Meat. See how that turned out. I have experience with this sentiment thing. When something makes people angry, I have confidence that the trend in question will continue for a very long time. I think negative rates are not an aberration and could become a semi-permanent feature of finance.

When people start to believe in negative rates, they will probably come to an end.

Lehman Brothers was a “bond house.” They were really good at fixed income—not so good at equities. Though equities did pretty well towards the end.

It was kind of hard not to be exposed to bonds at Lehman, even if you did work in equities. If you recall, the Barclays bond indices that we have today used to be Lehman bond indices. I got a lot of customer flow in the 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, TLT, and it was because Lehman had the index.

I also took six weeks of bond math when I joined the firm in the summer of 2001, and most of it stuck with me.

A lot has changed since then. Most of the trading activity in US Treasurys is electronic. Back then, it was all high-touch—carried out by actual humans.

A lot has remained the same. It’s still fundamentally the same market that it was 20 years ago. There’s a lot more debt, but one thing that has remained constant is how difficult it is to trade off of supply—the idea that more bonds makes rates go higher. And, people believe strange things about the bond market these days—they think more supply makes interest rates go down.

If you think things are stupid, they will probably get more stupid. You can put that on my tombstone.

Jared Dillian

I have had a lot of questions on this, so here we go.

Do I buy individual bonds or bond funds?

I have owned individual bonds in the past, for speculative reasons. If you have your account at one of the major brokerages, they are not that hard to buy.

But individual bonds are not as liquid as stocks. The bid-ask spread (a measure of market liquidity) on a typical bond could be two points wide for a retail client. That is pretty illiquid, so it’s not the type of thing you day-trade.

Short-dated high-grade corporates will be a bit tighter, but it’s not .01 wide like a stock. Basically, if you buy individual bonds, you are probably holding them to maturity. This is especially true in the case of munis, most of which are very illiquid.

I will say that owning individual bonds is fun. It is cool when the semiannual interest payment hits your account. Another thing people often forget—when you buy them, you buy them with accrued interest.

But the big problem with owning individual bonds is that it is hard to achieve diversification unless you have a lot of money. You can achieve diversification with 20-30 stocks. If you own 20-30 bonds, you are still not very well diversified—if one or two of them defaults, your entire returns go down the drain. This is why people buy bond funds, which have hundreds and hundreds of bonds.

If you really want to be an investor in a diversified portfolio of individual bonds, you are probably going to need $5-$10 million, plus another couple of million for your stock portfolio.

Or you can do what I do, which is punt individual bonds around from time to time.

With individual bonds, if you are right you make a little. If you are wrong, you lose everything. Investing in individual bonds is a negative art.

Investing in bond funds is not.

There are a lot of bond funds to choose from. This is pedantic enough, I am not going to go through them all here.

Let’s assume that we are talking about a corporate bond fund of some sort, high grade or high yield. It has hundreds of bonds.

How do you evaluate bond funds?

Well, you look at the yield. And you look at the credit quality. These are things that will be in the prospectus or fact sheet. If you are like me, you will dig in to see what’s in the portfolio.

Pro tip: the manager of a bond fund counts. Even more than a stock fund. The best managers will put up the best returns year after year. Also, don’t trust the Morningstar ratings, because the Morningstar folks look at costs, which you shouldn’t care about.

(I mean, if a corporate bond fund has a current yield of 3% and has 1.50% operating expenses, then yes, you care about costs. By all means, look at the operating expenses. But unless they are grossly out of whack, you shouldn’t care all that much).

Bond ETFs, of course, are an alternative. Maybe.

Some of the most popular bond ETFs—LQD (investment grade corporate) and HYG (high yield corporate) are not something I would recommend, precisely because they are popular. As you know, most ETFs track an index. This is true of bond ETFs.

But the bond indices have a lot of bonds, and it is impractical for a bond ETF market-maker to own every single bond in the index. So they own a subset of those bonds, and those bonds tend to be quite expensive. You, the retail investor, end up overpaying for bonds, which means you get lower yields.

Compare the yields of bond ETFs to open-end mutual funds—you will see they are much lower.

Also, the ETFs tend to be trading vehicles. There are options listed on these ETFs, and short-term trading activity can really push them around.

Some dumb people have said that these ETFs will “blow up” someday, but that’s not true. Of all the things to worry about with bond ETFS, that is not one of them.

Building a portfolio of bond funds is a bit complicated. Basically, you’re going to want a mix of Treasury, investment grade, high yield, municipal, and international funds, if you want to be diversified.

If you have a view on rates, you can overweight or underweight Treasurys.

If you have a view on credit, you can overweight or underweight corporate bond funds.

Etc.

I will say that people are pretty loaded up on high yield these days, because interest rates are so skinny. But high yield is pretty strongly correlated with the equity market, so at some point people might find that they do not have the diversification they thought they had.

There is plenty more on this but we’re about out of time. I hope this helped the pile of you who wrote in with bonds vs. bond fund questions.

There is a lot to understand with bonds, which is, I think, a big reason people don’t invest in them as much as they really, really should.

We’ll be throwing you a lifeline soon.

Thanks for tuning in. Be sure to check out my latest music: Very Exotic.

Jared Dillian

Since I started this 10th Man bond series, you guys seem to be split broadly into two camps.

On one side, there are people who remain anti-bonds. Or at least, anti-investing-more-in-bonds.

On the other side, there are the “yes, but” folks, who get why it’s important but feel blocked from doing much about it, for different reasons.

Anyway, as I said last week, we’ll be throwing you a lifeline soon. I’m working on something pretty important that is a) going to make bond investing a lot easier and b) be beneficial even if you’re anti-bonds (yes, really).

For now though, let’s continue with an article based on a question I’m getting from lots of you: how would you build a bond portfolio?

The best way to build a bond portfolio is to start by thinking about the risks.

A portfolio of bonds can go down, you know.

Yes, I know that US Treasurys cannot technically default (or at least, they haven’t so far). But they can decline in price, and the decline can be substantial.

For example, if long term interest rates go up a lot—say 2% or so—the price of a 30-year Treasury bond could drop by as much as 40%. That’s a scary number. Most people aren’t worried about that right now. They may be someday.

So we are definitely concerned about the direction of interest rates, known as duration risk. For US Treasury bonds, that is pretty much the only risk.

For other types of bonds, there are other risks. Corporate bonds can and do default. They haven’t in a while, but they will someday. More importantly, the price of these bonds will decline as the market perceives companies to be less credit worthy. In the investment community, this is known as spread widening. The spread between corporate interest rates and Treasury interest rates will widen.

In the last credit meltdown in 2015, led by energy credits, high yield spreads widened to about 700 basis points over Treasurys.

That’s a bunch of gobbledygook to many people. What does that mean to me as an investor in a bond mutual fund?

Well, if you own a high-quality investment grade corporate bond fund, the most it can probably go down because of credit concerns is about 5-7%. If it is a fund that is concentrated in BBB credits, perhaps a bit more.

If you own a high yield bond fund that focuses on BB credits, your downside is probably capped at around 20%. If it owns mostly speculative CCC credits, you could lose 30% or more. This is also true for convertible bond funds.

With international bonds, it is very much dependent on the situation, but emerging market bonds tend to be very economically sensitive and the downside could be large if we have a global recession.

Mortgage-backed securities are pretty boring most of the time, except in 2008, or if interest rates rise rapidly.

One day, municipal bonds will be very, very exciting. Although people have been saying that for 15 years or more.

Now that we know the risks, let’s build a portfolio.

What is your income? If it is north of $300K-$400K, you will want to consider owning lots of municipal bonds. Yes, I’ve heard all the arguments against munis—unfunded public pensions leading to muni bond defaults, blah blah blah. Maybe that is an issue in the next recession. Maybe not.

For the rest of the portfolio, you will want a mix of Treasury and corporate bonds. With yields this low, people are tempted to massively overweight corporates. I understand that sentiment.

By the way, one thing that is poorly understood about investment grade corporate bonds is that they are also very sensitive to interest rates. When Apple issued their first bonds back in 2013, people were surprised to see 10% of the value evaporate in a month—all on duration.

High yield bonds have a little exposure to interest rates (especially with the low coupons these days), but not much. Mostly, they are correlated with stocks.

So:

Treasury—all interest rate risk.

Investment grade corporates—some credit risk, some interest rate risk.

High yield corporates—mostly credit risk (they behave like stocks).

I don’t have a rubric here for what you should do, but your instincts on this—to overweight corporates to get more yield—are probably bad. This is actually the wrong time to be reaching for yield.

It’s the right time to be reaching for safety. Had you done so 8 months ago, you would be pretty happy today. Treasury bonds are up over 20% this year.

The other thing you need to consider when building a bond portfolio is the length of maturity you want.

Short-term bonds = less interest rate risk and less credit risk.

Long-term bonds = more interest rate risk and more credit risk.

You could just do it naively and pick a range of maturities. I’m not going to talk about it here, but you might want to do some research on bond laddering, the idea of which is to spread your risk along the interest rate curve.

The school of thought is that you want to match your bond maturities with your liabilities.

If you are going to retire in 30 years, you probably want 30 year bonds. If you are going to send a child to college in 10 years, you probably want 10 year bonds.

If you have a view on interest rates, that can help. For example, I think that the Fed is likely to cut rates to zero and beyond. This would make shorter maturities more attractive.

Once you put together your portfolio, you can figure out the weighted average maturity. A typical bond portfolio has a weighted average maturity of 5-7 years. If you are worried about interest rates or credit, you can make it shorter, or vice versa.

The key here is diversification. A portfolio full of municipal bonds will expose you to, well, the idiosyncratic risk that muni credit blows up.

And yes, this is more art than science.

And I know it’s not straight-forward. One reader said this recently: “I went into bonds hoping to ease up on time needed on my portfolio, but now I think shares are simpler!”

He’s not wrong.

But the bond market is much larger than the stock market. For many reasons, it is not clever to avoid it altogether.

Jared Dillian

I’m pretty sure this is the first ever Q&A issue we’ve done in The 10th Man. Since I started the Bond Series, a not insignificant number of emails have been landing in my inbox, week after week.

Turns out bonds generate a lot of questions. That doesn’t surprise me.

Anyway, from convexity and liquidity to the best income investing to the economics story of the century, I’ve answered as many questions as I can here. Enjoy.

Q. Why do people use yield, rate, price, coupon interchangeably?

The coupon of the bond is the actual cash that the bond spits out semi-annually. The coupon rate is the percentage of par (face value) that the coupon represents. The current yield is the coupon divided by the current price of the bond (which may not be par). The yield to maturity is the theoretical rate of return you get if you hold the bond to maturity. The price is, well, the price.

Q. Please explain convexity like I’m 5 years old.

Convexity means that when yields go down, bond prices go up more, and when yields go up, bond prices go down less.

A 5-year-old probably doesn’t know what a bond is, but this is the best I can do.

Q. How does liquidity affect the bond market? When do I need to worry about liquidity?

In the old days, liquidity was not much of a concern. The high yield bond fund I had with Vanguard years ago had checkwriting privileges. Imagine that!

The bond market is not terribly liquid these days, and that is mostly because of regulation and capital requirements for financial institutions.

If you own individual bonds and you want to sell them during times of stress, the bid-ask spread may be very wide, or you may not be able to sell them at all. This is especially the case with off-the-run muni bonds or less liquid high yield bonds. A good guide here is “sell when you can, not when you have to.”

If you own bond funds, the likelihood that redemptions could be gated is not zero. This is a much larger issue that regulators are trying to deal with. When it comes to liquidity, open-end funds are actually more dangerous than ETFs.

Q. If I want to own bonds for income, what do I do in this interest rate environment?

Income investing is hard—you want to do it in a smart, sustainable way. People’s instincts are usually wrong on this—since yields are low, they like to take on additional risk to get more yield. But the reason yields are low is because risk is underpriced—and this often does not work out well.

I would resist the urge to take on additional credit risk for more yield, and just make do with things like Treasurys and munis. By the way, all the good income investing is in stocks these days.

Q. How reliable are the bond rating systems?

Bond rating systems are good but they tend to be a bit backward-looking. They tell you where the company/country has been, not where it is going. Enron and Lehman Brothers were both AA credits, for example.

Q. What is the role of TIPS vs regular government bonds vs other inflation hedges like gold in a portfolio?

Actually, the one interesting thing about TIPS that is not being discussed is that they cannot pay you a negative yield, unlike straight bonds. If yields continue to decline, TIPS will become very, very interesting.

Q. I’m in my 30s. If the market goes down 50% next year, so what? We use wages to fund our current life. So, how should someone in my situation think about bonds?

True—you have a lot of time left on the clock to invest in stocks.

You invest in bonds for diversification purposes—it reduces the volatility of your portfolio and increases the risk/return characteristics.

Q. I've read that bonds should go in your tax-sheltered retirement accounts and stocks in your non-retirement accounts due to the tax treatment of bond interest. This seems a little unintuitive to me… Can you explain?

I’m not the expert on taxes, but I know this much: don’t put muni bonds in your IRA.

Q. Jared, as of today you can get 2-2.5% on cash in savings programs. Why is that not an appropriate alternative to bonds? What is wrong with a 65% cash 35% equities investment?

Congratulations—you have just discovered the yield curve! Right now, you are getting approximately the same yield on short maturities that you do on long maturities. Why take on the additional duration risk of long maturity bonds if you are not being compensated for it? Your instincts are correct—if you can get 2+% yields on a savings account, you are probably better off with that.

Q. Over the last few months, I’ve assumed a large percentage of stocks that are dividend plays, as I’m starting to think of these as similar to bonds. Am I embarking on a journey into a world of volatility or can I think of these stocks as low volatility plays that will provide a consistent income?

REITs and Utilities are similar to bonds, as are high-yielding telecoms and tobacco stocks. They’re actually better income plays at this point than bonds.

Q. What’s your outlook on interest rates both in the US and worldwide over the medium-term?

I expect short-term interest rates to decline globally, and I expect long rates to stabilize once central banks have communicated that they are acting aggressively enough.

Q. If we got to negative yields in the USA, what likely impacts do you see on all financial markets?

There will be distortions, some that we can see (hoarding cash, gold prices skyrocketing), and others that we can’t.

One interesting thing that is happening is that we’ve had a huge drop in mortgage rates and it really hasn’t stimulated the housing market at all. People call this “pushing on a string.”

Q. What are your thoughts on demographic factors in USA, Japan, and Europe driving demand for bonds?

Honestly, I think one of the reasons that yields are dropping is because of the demographic factors that were being discussed in 2012. Population growth is slowing a lot faster than people anticipated. This is really the economics story of the century.

I don’t think demographics are the whole story, but the implication is that it is going to be very difficult for yields to rise in the future.

Q. What if anything would make you sell out of your bond investments?

If I believe that inflation was likely to ramp, or that the Fed would be able to resist both Trump and market pressures and keep interest rates high. Neither of these is likely.

Q. What scenarios should you not be invested in bonds?

When there is lots of inflation.

Q. If I want to increase my allocation to bonds, should I wait until this rally ends?

It doesn’t make any more sense to try to market-time the bond market than it does the stock market. If you don’t have an informed opinion on the direction of interest rates, the best course of action is just to dollar cost average—just like you would do with a stock fund.

Q. I want to educate myself on bonds – what sources do you recommend, particularly books?

You can get one of the Fabozzi books on bonds off of Amazon, but they tend to be pretty impenetrable.

I have actually found that there are not many great sources, especially for individual investors. I think that’s one of the reasons there is such a knowledge gap about bonds.

I am working on that though.

Q. Bonds yes, but what type of bonds?

See above. An important announcement is coming you way soon. More next week.

Jared Dillian

Baby boomers, man.

Before I begin, a good rule of thumb for anything I write: don’t take anything personally.

Baby Boomers are the worst investors in the world.

I have seen it with my own two eyes. They got gorked up on dot-com stocks in 1999, then got rinsed. They got gorked up on stocks again in 2007, then got rinsed.

They are gorked up on stocks again.

Have you ever tried talking to a Baby Boomer about their asset allocation?

Hey Dad… uh, you’re getting close to retirement. Don’t you think you should lighten up on stocks?

We all know how that conversation goes. Not well. Especially with cable news turned up to 11 in the background.

In the old days, they had this rule of thumb that your age should be your percentage allocation to bonds. So if you were 70 years old, you should have a 70% allocation to bonds.

The reason is simple. When you’re close to retirement, you don’t want to risk losing it all. You want something safe, that spits out some income.

In my travels, I would say that the average Baby Boomer has an 80%-90% allocation to stocks. When the sane, sober Generation Xers try to have a conversation about de-risking, they get told to beat it.

For whatever reason, Baby Boomers have an insane tolerance for risk. And it has not served them well. They are wealthy, but they could have been wealthier. They are credulous. If a bubble pops up, they believe in it, and dive in headfirst, whether it’s cannabis or dot com or security stocks. Not bitcoin—that posed a technological hurdle they could not overcome.

Ironically, the one bull market they have not been sucked into is bonds. Which is the one thing they should have been investing in all along.

Bonds are for old people—although not just for old people—and yet old people don’t want them.

A little louder, for the Tommy Bahama shirts in the back:

If the stock market crashes, you are all screwed.

Pretend you have $2,000,000 saved for retirement. In 2008, the stock market went down nearly 60%.

If the stock market goes down 60% again, you will have $800,000, which will drastically reduce your standard of living in retirement.

Theoretically this would get your attention, but it probably doesn’t because you don’t think it’s possible that the stock market would go down 60 percent again.

You’re right. It might go down more than 60%. There is precedent for that, too.

This is why stocks are unsuitable for all different kinds of people—they make sense for people in their 20s and 30s, and also 40s, but as you get older you have to cut risk dramatically.

This used to be the conventional wisdom. Not anymore. What happened?

What happened was an 11-year bull market. There are lots of investors whose investing career has not spanned a full cycle. Only the first half of the cycle, which is less instructive than the second half.

Boomers have been through a bunch of cycles and, as a cohort, have learned precisely zero lessons from them.

I will answer this question one more time.

“Why invest in bonds when interest rates are so low—when it’s clearly a bubble?”

But most of all…

Stocks may have gone down almost 60% from 2007-2009, but a 35/65 portfolio of stocks and bonds only went down 24%.

That fact remains relevant whether you believe bonds are “in a bubble” or not. I have a bit more to say on this, which I will send to you tomorrow.

Here’s the thing—financial markets simply aren’t fair. They’re not fair to normal human beings with normal human emotions, people who get excited by high prices and demoralized by low prices.

A humblebrag: whether because of genetics or study or whatever, I have been blessed with the ability to do the opposite: I get excited by low prices and demoralized by high prices.

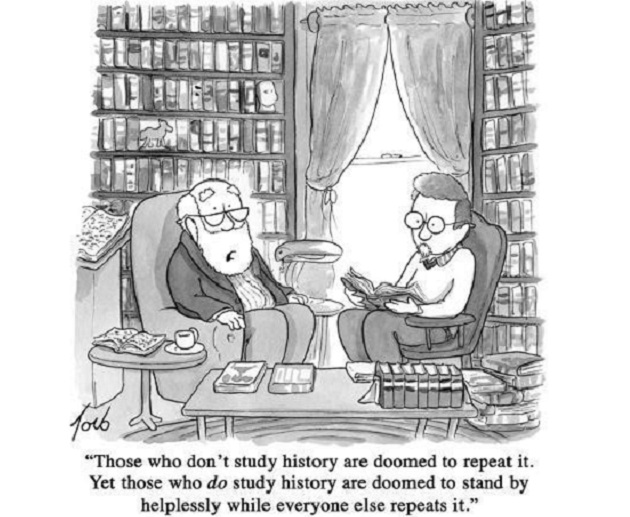

Source: New Yorker

Many financial advisors (lots of them CFAs and CFPs) are motivated by one thing and one thing only—retaining assets. Before any financial advisors get angry and hit ‘reply’ here, I'll refer you back to my earlier rule of thumb: don't take anything I write personally. If you're reading this article, you're probably not the type of financial advisor I'm talking about.

Anyway, the worst-case scenario for these advisors is that you pull your account.

Most people don’t pull their accounts when they lose money—it is easy for the advisor to shift blame to the market. They pull their accounts when they don’t make as much money as everyone else.

If you went to your advisor and asked to shift your asset allocation to bonds, he or she is going to put up a massive fight. Because your expected return will drop, and you won’t make as much money as “everyone else.” If you’re all in stocks, and you lose money, well, so will everyone else.

That is a fight you might not win. If you told him about this guy on the internet yammering on about bonds, he would probably tell you that I am a crank.

Financial advisors are many things—relationship managers, mainly—but the majority of them are not market experts. His opinion is no better or worse than the person on CNBC.

I have a strong suspicion that very few Baby Boomers will take my advice. Because, you know, Baby Boomers.

It’s not about my giant ego. I try to prevent unnecessary misery. How am I doing?

I give myself a D+.

Jared Dillian

Hi everyone.

You’ve probably noticed that we’ve spent an inordinate amount of time recently talking about bonds. That is by design, because:

These discussions have been met with more-than-occasional protests from some readers about the wisdom of adding bonds to a portfolio when interest rates are so low. I’ve addressed these concerns numerous times.

On the other hand, it’s been pretty great to see emails rolling in with people either telling me they own a lot of bonds or telling me they want to know more about bonds.

There have also been a lot of thoughtful points made and sent in. So many that I can’t reply to them all, but thank you, sincerely, for helping me with my thought process around this.

Anyway, there are arguments against bonds, for sure—but not when the average investor owns practically none to begin with.

Many people simply are ignorant of how bonds work. Some people have an understanding of the relationship between interest rates and bond prices, but they don’t really know how or why it works.

There are lots of people out there who know a bit about stocks. This gives them beer muscles—they know just enough to be dangerous.

If you watch CNBC for any length of time, you might be left with the impression that stocks are the most important thing in the world.

They are not.

The bond market is much bigger and more important. Stocks are practically inconsequential.

I’ve had a pretty comprehensive bond education—one semester in business school, plus 6 weeks of intensive bond training at Lehman Brothers, plus extracurricular reading, plus a full seven years trading interest rate products, including derivatives.

I’ve always felt that the average investor was woefully underprepared for investing in bonds, and that’s why…

The Bond Masterclass—which I wrote myself—is a thorough education on bonds for the average investor, and most experienced investors as well.

You’ll learn about interest rate risk, duration and convexity, credit, the different varieties of bonds—you name it.

It’s like getting a college class in one publication that explains things in Jared Dillian-style plain language.

And it’s a lot cheaper than a semester in school, I can tell you that.

Look, at the end of it, you may decide that you’re not interested in investing in bonds right now—and that’s fine. But you will have made an informed decision.

And the Bond Masterclass is designed to be your go-to bond guide for all time (or close to it). If things change and you decide that bonds are a good idea for you in a year or two or three or 10, then the information in the Masterclass will still be valid.

And yet there is an investing-right-now component too, of course.

It’s very, very cool. I’m super proud of it, and I’m especially proud that this Masterclass is really going to help a lot of people.

But that’s not all.

|

|

|

|

|

The Bond Masterclass is part of a larger effort to educate the public on personal finances, the use of debt, and the basics of investing. This effort is called Jared Dillian Money.

Jared Dillian Money is still in its infancy, but over time, I will (with a little help) be developing a suite of products to educate people on basic financial concepts.

Many people today would consider me to be a financial expert, but it didn’t start out that way. I was completely ignorant of finance until about age 23, at which point I dove headlong into learning everything there was to know about the capital markets.

Back then, the only resource available to me was the local used bookstore. Nowadays, there is a lot of stuff online, but some of it is good and some of it is terrible and it’s an awful time-sink for people to figure out which is which. I want Jared Dillian Money to be one-stop shopping for basic, smart, useful, financial knowledge.

In furtherance of that effort, I have started a daily two-hour radio show called The Jared Dillian Show. We’re currently broadcasting on one station, but the goal is to increase its footprint significantly over time. If you’re not in range of the show, you can always listen to the podcasts.

I invite you to explore the website and see what’s there—we already have a few things available, though some of it, like advice on getting out of debt, will likely be too basic for the average 10th Man reader. But maybe not!

Regardless, I wanted to give The 10th Man readers an update on everything that is going on.

And yes, the Bond Masterclass is a Jared Dillian Money product.

I got to a certain point in my career and I took a step back and evaluated what I was doing. Basically, I was helping a lot of people who didn’t really need a lot of help. I thought to myself—there must be a way I can help the people who really need help. I talked to Ed and Olivier (of Mauldin Economics), and Jared Dillian Money was born.

In my travels, I’ve found that the average person’s knowledge of finance and investing is tragically limited. We’re setting out to fix that.

As for The Bond Masterclass, unless you traded bonds at an institutional level, you can probably benefit from what’s in this guide. There is something for everyone.

And it’s not a dense textbook with lots of equations (although we did put the equations in if you are interested)—it’s easy to understand and will make an immediate impact on your knowledge of bonds.

Jared Dillian

You can join Jared Dillian's Bond Masterclass right now (and save 50% through October 3 only)

Copyright © 2019 Mauldin Economics