Thoughts from the Frontline: It’s Not Over Till the Fat Lady Goes on a P/E Diet

- Shannon Staton

- |

- July 13, 2015

- |

- Comments

For the vast majority of investors, portfolio returns are generated by the equity markets or at a minimum heavily influenced by the equity markets. We have enjoyed an almost six-year bull market run in the stock market, which has helped heal portfolios after the devastating market crash of the Great Recession. So much so that many prominent market analysts have proclaimed the beginning of a new secular bull market. If we have indeed entered such a new phase, we need to recognize it for what it is, because – as I’ve written for 17 years – the style of investing that is appropriate for a secular bull market is almost the exact opposite of what is appropriate for a secular bear market. I think that most analysts would agree with that last statement. The disagreements would revolve around whether we are in a secular bull or a secular bear market.

Thus the answer to the seemingly arcane question of whether we are in a secular bull or bear market makes a great difference in the proper positioning of your portfolios. And getting it wrong can have serious consequences.

Towards the latter part of the ’90s and especially in the early part of last decade, I was rather aggressively asserting in this letter that we should look at whether we are in a secular bull or bear market – not in terms of price but in terms of valuation. Early in that period, Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research, who was then based in Dallas, reached out to me; and we began to collaborate on a series of articles on the topic of secular bull and bear markets, a series that we want to continue today. Longtime readers know that I’m a big fan of Ed’s website at www.CrestmontResearch.com. It’s a treasure trove of fabulous charts and data on cycles and market returns. Ed has been working on a video series (we will offer a few free links below) to explain market cycles.

I want to provide a little current context before we jump into the argument about whether we are in a secular bull or bear market. For some time now, I’ve been saying that the US economy should bump along in the Muddle Through range of about 2% GDP growth. The risk to that forecast is not from something internal to the United States but from what economists call an exogenous shock, that is, one from outside the US. In particular I have said that a crisis in both Europe and China at the same time would be very negative for both US and global growth. We now see potential crises in both regions. It would be convenient if they could arrange not to have them at the same time. But those who are paying attention to global markets are certainly experiencing a bit of market heartburn as they watch both China and Europe manifest the volatility that they have over the last few weeks. I will become far less sanguine about the US economy if full-blown crises develop in those two regions.

There are observers who think the Greek crisis will be contained, and then there are equally astute but pessimistic observers, like Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, who wrote this week about the potential for a full-scale European meltdown. His recent column entitled “Europe Is Blowing Itself Apart over Greece – and Nobody Seems Able to Stop It” is reflective of those who think the European monetary experiment is problematic. It now appears that Tsipras has essentially caved on a number of issues in order to get a deal. The deal he has proposed reads almost exactly like the one the Greek referendum overwhelmingly rejected.

My own personal view is that, if this deal is agreed upon, it simply postpones the crisis for a period of time, as Greece simply has no way to grow itself out of its debt dilemma. And it is not altogether clear that Tsipras can hold his coalition together, given the referendum. He might actually need the opposition to get this deal passed, which becomes problematical for him, as it might force him to call an election. But the banks would open, and Greek life would go on until the Greeks run out of money again in the sadly not-too-distant future, as there is no way on God’s green earth they can meet the growth requirements that this deal demands.

The monetary union is an absurd creation based on political hopes, not economic reality. Politics can keep it together for longer than it should otherwise exist, but unless the entire southern periphery of Europe turns German in character, the peripheral nations are going to suffer under a monetary policy not designed for their economies. That ill-fitting economic straitjacket is going to mean slower growth and higher unemployment and fiscal instability. How long will they endure that? So far, a lot longer than I thought they could, 15 years ago.

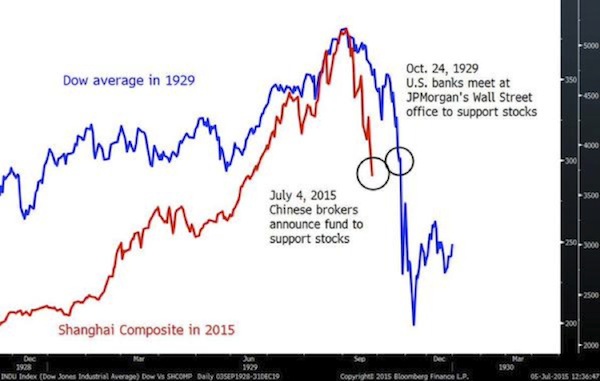

China’s stock markets are having a meltdown, although there has been a rebound the last few days as the Chinese government has stepped in with the decision to destroy their markets in order to save them. My friend Art Cashin commented that it is amazing what you can do if you tell people that they will either buy stocks and make them go up or get executed. It certainly clarifies your trading position. Further, the Chinese government basically created a rule which said that anybody who owns more than 5% of any particular equity issuance is not allowed to sell for the next six months. Neither are directors, supervisors, or senior management of any public company. The government has evidently pressured banks into creating a buying consortium. Historians who are familiar with the stock market crash of 1929 will see an interesting parallel, illustrated in the chart below (sent to me by my friend Murat Koprulu).

Hundreds of Chinese stocks have been taken off the market because they are essentially locked limit down or because company management simply halted trading in their shares, as there seemed to be no bottom to the pricing. That is an interesting way to run a supposedly liquid equity market exchange. And it creates an overhang, in that, under the current rules of the exchange, those hundreds of stocks have to go back on the market within 30 days. Theoretically, they were falling in value, which was why they were taken off the market to begin with. Will their valuations somehow magically change?

I wonder if all the major indexing firms are happy with their recent decisions to include China as a major portion of their indexes, given that liquidity in their markets is available only when markets are going up. Just curious, but how in the Wide, Wide World of Sports do you price or even maintain an index if you can’t sell and have daily liquidity and price discovery? If 7% of your index is based on a valuation that is not real, what price do you then base daily liquidity on? The last trade? So the seller gets out at a price that might be significantly higher than what the issue would actually trade at? Who sues whom? Or maybe the issue then trades higher, not lower, so that the seller should have gotten more? Index fund managers have to be pulling their hair out over this one.

Is this collapse of the Chinese market just the result of irrational exuberance, or is there something more fundamental going on? We will have to watch the situation carefully in the coming weeks.

By the way, China is far more critical to the global economy than Greece is. So much so that I recently asked a number of my friends to give me their best thoughts on China. These are experts in markets, demographics, economics, geopolitics, and so on, all with specialties in China. I’ve compiled those thoughts along with my own and those of my co-author, Worth Wray, in an e-book called A Great Leap Forward? You can get it on Amazon, iTunes, and Nook for a mere $8.99. It is an easy read that will give you an understanding of China’s challenges, from the best China experts we could find. Now, let’s talk about where the market is going in the US.

Are We There Yet? Secular Stock Market Cycle Status

By John Mauldin and Ed Easterling

We were both talking about secular bear markets back in 1999 and 2000. It’s been 15 years. Aren’t we there yet? Isn’t the stock market rising?

Of course you’re getting impatient; so are we. When will the stock market shift from secular bear to secular bull – or did it already? The implications are significant. Through much of the 2000s and into the 2010s, individual and institutional investors have weathered quite a storm of low returns and high volatility. Are we done being battered? From today, can you reasonably expect above-average secular bull returns like we saw in the 1980s and ’90s … or do we face another decade or longer of below-average secular bear returns? [For a 3-minute video explaining the term secular, click this link.]

In short, we use secular to describe a particular valuation environment. If you use valuations as a tool for thinking about cycles, the cycles become much more clear and easily understandable. Simply using price gives you no objective criterion for determining where you are in a long-term cycle. Within our longer-term secular designations there can be numerous and significant cyclical bull and bear markets, which are determined by price and not valuations.

For years, analysts and pundits throughout the industry have agreed (though it took a number of years for many of them to come around) that the new millennium brought with it secular bear conditions. In the past few years, however, opinions have once again diverged. Notable heavyweights, including Guggenheim Investments, Raymond James, and BofA Merrill Lynch, are on the record that the stock market has now entered a long-term secular bull market. (They are certainly not the only ones, but they do provide nifty charts that make it easy to analyze their thoughts.)

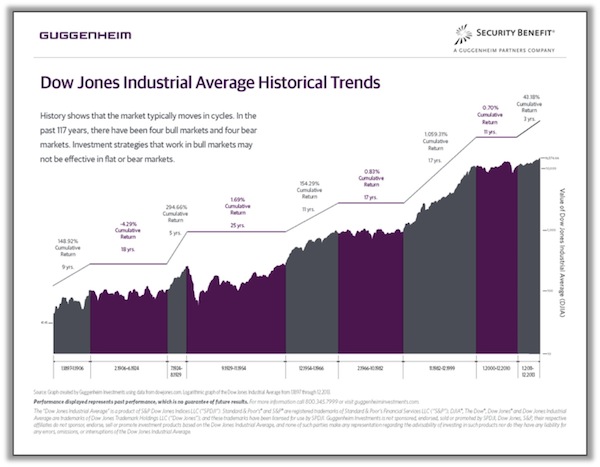

As shown in Figure 1, Guggenheim clearly marks the transition point between the end of the secular bear that got underway in January 2000 and the start of the new secular bull market. They place that transition point at December 2010, so that by their reckoning the secular bear lasted eleven years and produced near-zero annualized returns. Then, according to Guggenheim, a new secular bull market was unleashed with New Year 2011.

Figure 1. Guggenheim Secular Bull Started January 2010

| From today, can you reasonably expect above-average secular bull returns like we saw in the 1980s and ’90s … or another decade or more of below-average secular bear returns? |

Now, four years and a cumulative +54% later, the Guggenheim chart appears to lead investors to expect a future of above-average secular bull returns. They are somewhat subtle about it: note the implicit investment advice in the upper-left area of the chart: “Investment strategies that work in bull markets may not be effective in flat or bear markets.”

So true! So pertinent to this article! In the next five or ten years, will the market surge ahead from the modest uptrend of the past four years, or will the chart action simply blend into the previous eleven-year secular bear? You’re probably not reading this article and others like it for entertaining chart designs; you likely want insights about how to position your portfolio. Okay, so what’s most likely for the next five or ten years: secular bull or secular bear? On to that in a moment, but first let us observe that Guggenheim is not alone in their outlook.

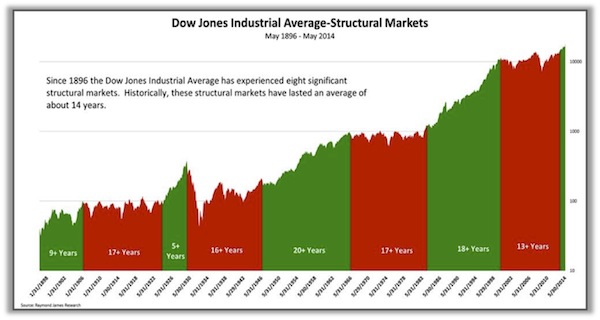

In Figure 2, [John’s good friend] the very savvy Jeffrey Saut at Raymond James marks the start of the new secular bull somewhat later than Guggenheim does. Based upon the chart’s legend and the notation that the previous secular bear lasted “13+ years,” Saut appears to call the transition in 2013.

Figure 2. Jeffrey Saut and Raymond James Have the Bull Greening Up in 2013

Saut’s secular bull green shoots are still developing roots. Nonetheless, his chart does lead the observer to hope that the right margin of the chart will fill with rising green lines. His way of designating secular periods results in an average term of about 14 years – so just over one down and around 12 to go for the new bull!

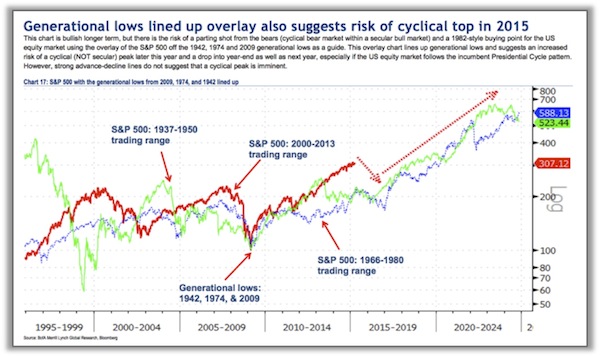

Last, yet clearly not least, in Figure 3 BofA Merrill Lynch completes the trifecta of secular bull market prognostications. The text in the upper part of the chart reads:

This chart is bullish longer term, but there is the risk of a parting shot from the bears (cyclical bear market within a secular bull market) and a 1982-style buying point for the US equity market using the overlay of the S&P 500 off the 1942, 1974 and 2009 generational lows as a guide. This overlay chart lines up generational lows and suggests an increased risk of a cyclical (NOT secular) peak later this year and a drop into year-end as well as next year, especially if the US equity market follows the incumbent Presidential Cycle pattern. However, strong advance-decline lines do not suggest that a cyclical peak is imminent.

BofA Merrill says that we’re in a secular bull market but that the best opportunities are still on the horizon – the near horizon! So 2015 or 2016 will see a pullback during which we should load the boat for a decade when, they predict, the stock market will double or triple in value. And while predicting a double or triple over the longer-term is optimistic, note that they are suggesting the market may return to levels seen at the beginning of 2000, a trajectory which to us seems more like a continuation of our secular bear cycle.

We fully agree that at some point the markets will double and triple. The question is, when does the runup start, and what do we do before that starting point?

Figure 3. BofA Merrill: Secular Bull More Than Doubling Over the Next Ten Years

If you are reading this article, you are likely a savvy investor with a few lessons of history (and losses of experience!) under your belt or as scars on your back. You are likely starting to feel a few contrarian hairs tingle on the back of your neck as you look across the oceans at Europe and China. You may even be seeing a few flashes of falling knives from the upcoming pullback suggested in Figure 3. So let’s explore the alternate view and the implications for investment strategy and portfolios.

Secular stock market cycles are long-term periods of above- and below-average returns. These longer-term periods consist of many shorter-term “cyclical” periods. During secular bull markets, the cyclical cycles occur along a generally rising path that features higher highs and higher lows. Thus in secular bull markets cyclical bulls surge, and cyclical bears are often somewhat muted.

During secular bear markets, however, the market’s path is generally sideways. As a result, the cyclical bulls and bears tend to be more balanced, with the bulls reversing the declines of bears and bears offsetting the runs of the bulls. The net result of these offsetting cycles is an extended period with disappointing cumulative returns.

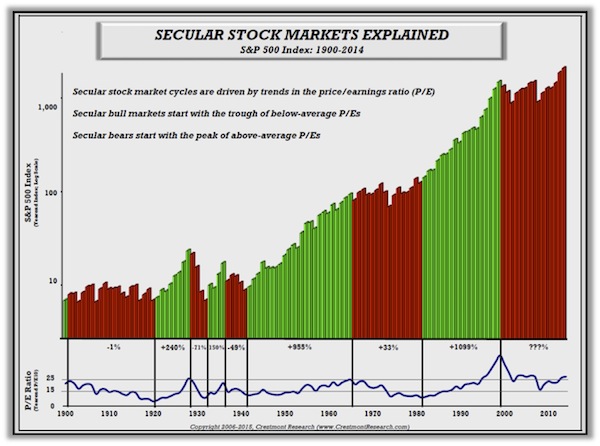

Figure 4. Crestmont Research: Secular Bear Remains; No Chance of Secular Bull

In contrast to the secular bull outlook from Guggenheim, Raymond James, and BofA Merrill, we believe – without hesitation or doubt – that the data shows the current cycle to be the continuation of a secular bear market, as shown in Figure 4. Further, we have a strong conviction that absent a dramatic crash and major deterioration in inflation-rate conditions, the prospect of a secular bull is far away. [For a 5-minute video discussing the “Secular Stock Markets Explained” chart above, click this link.]

The most significant difference across the four secular charts presented thus far is that the Crestmont chart prominently includes what we believe is the true driver of secular stock market cycles: the price/earnings ratio (which is, in turn, influenced by inflation, as we will explain below). Note the blue line near the bottom of the chart. The wavy price/earnings ratio (P/E) cycle reflects the level and trend of stock market valuation. Red-bar secular bear markets are driven by a declining trend in the P/E, and green-bar secular bulls are driven by a rising P/E trend. Neither time nor magnitude are relevant.

You can’t really have a secular bull market without rising price-to-earnings ratios. You can have some astounding cyclical runs that will eventually return to valuation-constrained averages, but the markets of the ’80s and ’90s required an ever-rising price-to-earnings ratio, as has every other bull market in the past.

Anybody who declares that we are in a secular bull market today is singularly focused on price, which is a derivative of the actual driver of market returns. It is a secondary relationship that is derived from valuation.

Secular stock market cycles are not driven by time-dependent phenomena. There is no mystical or explainable term of years over which the market rides waves of bulls and bears. (There are some interesting coincidences here and there but certainly not enough data points to draw any firm conclusions.) Some chart designers conveniently shift years or combine periods to create such an apparent effect, yet time is not a reliable driver of these periods. (For the most part, none of the previously displayed secular charts resort to this technique.)

Likewise, secular stock market cycles are not driven by magnitude; they don’t start and stop at new highs or lows (or relate to certain levels of gain or breakeven). If such a methodology were consistently applied to longer-term secular cycles, the results would be disappointing. That said, the shorter-term cyclical cycles within secular cycles can often be well defined using such a technique. Secular cycles, on the other hand, can be understood only through an examination of the underlying fundamental principles that drive them.

One such principle is the P/E cycle, which is driven by the effect that the inflation rate has on valuations. As the inflation rate rises, the present value of future earnings falls. Prices (the P in P/E) decline, with minimal immediate effect on current earnings. Thus, as P falls and E stays nearly the same, the result is a decline in P/E.

Deflation also drives P/E lower. Deflation is a declining trend of future nominal prices. A series of declining future earnings is worth less than stable or rising earnings; thus a trend toward deflation drives P/E lower. As deflation worsens, the value of the market (and thus P/E) declines even further.

Therefore, a trend in the inflation rate away from low, stable inflation drives P/E lower, while a trend in the inflation rate back toward low, stable inflation drives P/E higher. Thus, as we see in Figure 4, the historical inflation rate cycle drives P/E, which in turn multiplies or offsets the growth in earnings to deliver above- or below-average returns.

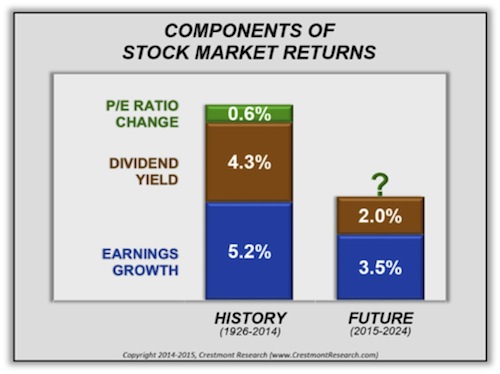

Let’s consider returns from another vantage point. Sometimes it can be revealing to break economic concepts into their component parts in order to better understand what drives them. For stock market returns, we have a fairly simple machine. There are only three components that combine to provide market returns. Any returns beyond the market return are the result of skill in portfolio selection or management.

As reflected in Figure 5, the three components are earnings growth, dividend yield, and any change in P/E over the holding period. The chart includes values from one of the most recognized series, the one provided by Professor Roger Ibbotson and published annually in the Ibbotson SBBI Classic Yearbook by Morningstar. The 2015 values are on pages 156-157. Through 2015 (the series starts in 1926), the cumulative annualized total return is 10.1%. Earnings growth contributed 5.22%; dividend yield added 4.25%; and the change in P/E topped it off with 0.63%.

Figure 5. Components of Stock Market Returns

Those historical values benefit from several factors that are not available today. First, the Ibbotson series starts in 1926, when P/E was 10.2. Over the 89 years since then, P/E has more than doubled. That added gains to the long-term total return. Going forward, however, another doubling of P/E from the currently high level is very unlikely.

Also, the low starting level of P/E in 1926 drove a high dividend yield in the long-term average return. The dividend yield is dividend dollars divided by market price index. For the S&P 500 Index, for example, the dividend yield is the total dividends of all 500 companies divided by the market index. When market valuation is relatively low (i.e., low P/E), dividend yield is higher than it is when the market P/E is higher. This is a direct mathematical relationship. The dividend yield of a market that is priced at a P/E of 10 would be twice the yield of a market that is priced at a P/E of 20 (assuming the same dividend dollars). Therefore, since the long-term historical stock market series starts at a P/E of 10.2, it includes a realized dividend yield of 4.25%. Had the starting P/E been at today’s level, the dividend yield would have been only about 2.1%. Of course, for today’s investors, not only does today’s high P/E explain why today’s dividend yield is near 2%; it also means that the dividend yield component of future returns will be near 2%.

What is a reasonable expectation for future returns? For this discussion, let’s assume that the future we are talking about is the next decade (2015-2024).

The first component is earnings growth; let’s assess its driver. Earnings growth is primarily driven by economic growth. Although profit margins vary across the business cycle and by industry and company, earnings for the stock market as a whole over the long term tend to track sales growth. Measures of the economy, including gross domestic product (GDP), tend to measure the aggregate sales of all companies in the economy. As a result, earnings growth has historically been similar to GDP growth. In reality, earnings growth for large-company indexes like the S&P 500 has been slightly lower than overall economic growth. The economy includes faster-growth small companies and start-ups that tend to outpace the more stable giants.

Over the past 89 years, the inflation rate has averaged 2.93%. Earnings growth is stated in nominal terms, with inflation adding to that component. The current level of inflation is about half of the historical average. If the inflation rate remains relatively low, as most analysts today believe it will, it would reduce the future nominal growth rate (compared to the historical average) by around 1.5%. In addition, most economists expect real economic growth (and thereby real earnings growth) to slow somewhat into the future. As a result, the estimate for future earnings growth is 3.5% annually, as shown in Figure 5 (and we need to remember that is in nominal terms).

Yes, the earnings estimate does assume relatively low inflation. And yes, a higher inflation rate would increase the contribution of earnings growth to total return. However, an increase in the inflation rate would have an even more significant offsetting effect on another component. More on that in a moment.

Dividend yield, as described previously, is highly dependent upon the level of P/E. The relatively high P/E ratio today portends a relatively modest dividend yield for any period starting in 2015. As a result, Figure 5 includes a contribution of 2.0% from the dividend yield component. Further, we have to remember that earnings as a percentage of GDP are close to all-time highs. In the past, earnings have been mean-reverting in terms of GDP. That would suggest that earnings growth could come under constraint over the next 10 years. There certainly doesn’t seem to be a great deal of room for an increase in overall earnings in terms of GDP.

The last component is the effect of a change in P/E. An increase in P/E adds to the returns provided by earnings and dividends; a decrease in P/E offsets those contributions to total return.

P/E is, in the final analysis and over the longer-term, driven by the inflation rate. When the inflation rate rises, the effect is an increase in interest rates and a decrease in P/E. When the inflation rate declines into deflation, the result is a decline in P/E. At low, stable inflation, the value of P/E rises to its peak. With today’s relatively low, stable inflation rate, a significant trend up or down in the inflation rate will decrease P/E. Therefore, a positive contribution to future total return from a significant increase in P/E is very unlikely.

Returning to the hopes of those who anticipate that higher inflation will add to the component of earnings growth, keep in mind that the adverse effect on the P/E component will more than offset any gains to the earnings component.

As a result, the near-best outlook for the next decade is an annualized total return of approximately 5.5%. Such a decade would essentially leave the current secular bear market suspended in a state of hibernation. That’s because hibernation assumes that the level of P/E does not change. As a result, at the end of the decade P/E would remain near current levels, and P/E will be no better positioned to double than it is today. For a transition out of secular bear into secular bull, the market must endure the effects of a decline in P/E to levels that will then enable it to double or triple. Such a decline would compromise the “optimistic” outlook of 5.5% annualized returns and instead deliver near zero return.

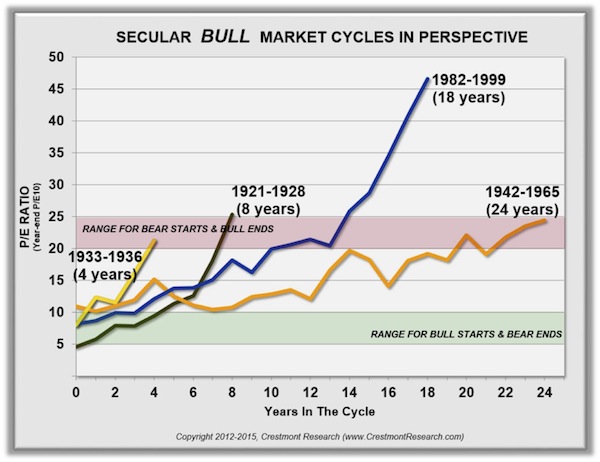

To illustrate this point, let’s review a chart that highlights the course of P/E in secular stock market cycles. Figure 6 reflects the level of P/E for each year of the past four secular bull markets since 1900. The number on the lower axis is the number of years in each cycle. [For a 5-minute video explaining the Secular Market Cycles charts in Figures 6 and 7, click this link.]

You’ll see that P/E during secular bull markets starts in the low-P/E green zone and treks upward to the higher-P/E red zone. In the most recent secular bull, which ended in a secular bubble, P/E reached the red zone and then doubled again. Regardless, this chart helps viewers to visualize that secular bull markets require a significant increase in P/E.

Figure 6. Secular Bull Market P/E

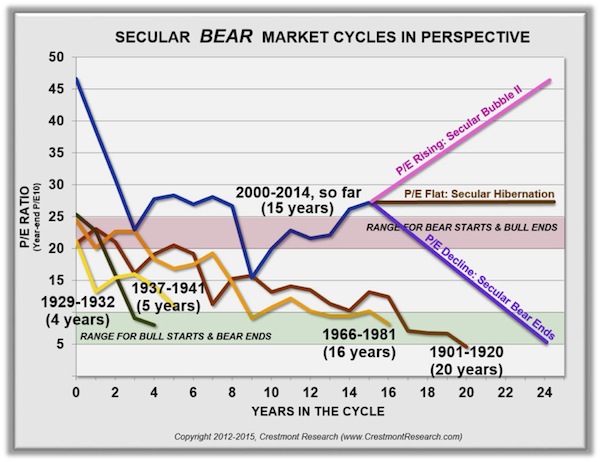

Figure 7 presents P/E during secular bear market periods. Since bears start where bulls end, the starting level for P/E in secular bear markets is generally in the red zone on this chart. The obvious exception is the most recent secular bull, whose dramatic end in a bubble gave our current secular bear quite an extra distance to travel. And for market analysts who are anchoring their current expectations from that last experience, the path ahead could be particularly treacherous.

Figure 7 includes three extra lines for illustration. They represent the three likely courses for P/E over the next decade. First, the purple line reflects a continuation and conclusion of this secular bear. New secular bull in 2025! The implication for the components analysis is that total return over the decade would be near zero as the decline in P/E offsets earnings growth and dividend yield.

Second, the brown line reflects a secular bear in hibernation. This scenario provides the near 5.5% annualized gain that was illustrated previously in Figure 5.

Third, the pink line reflects a repeat of the late 1990s: a surge of P/E to irrationally exuberant levels. Although this scenario is possible, very few professionals (and not even the most optimistic pundits) would advocate basing your investment portfolio and lifestyle distributions on this outcome. Nonetheless, for the blissfully hopeful, this outlook would deliver annualized total returns just over the long-term average of 10%. It would not repeat the 1980s and ’90s secular bull results, because the starting level of P/E is so much higher in 2015 than it was in 1982.

Figure 7. Secular Bear Market P/E

There is a third constituency of outlooks for stock market returns over the next decade or so. This group of esteemed market and investment professionals doesn’t typically speak in secular-cycle terminology but rather tends to present forecasts for seven- or ten-year returns. Two of the more prominent members of this group are Jeremy Grantham and John Hussman. The current longer-term outlook from each of them indicates near-zero returns from US large-cap stocks.

This outcome can be explained using the previous approach of dissecting the components of stock market returns. Both Grantham and Hussman assume reversion to the mean. That is, their forecasts include the assumption that P/E will be at or near its long-term average at the end of the forecast period. They either don’t see the inflation rate as the driver of P/E and/or simply believe that the average value is the most likely level in the future.

If P/E happens to decline to its historical average over the next seven- to ten-year period, that downtrend will nearly offset the positive contribution of earnings growth and dividend yield. Therefore, Grantham and Hussman implicitly believe that we’re in a secular bear market, even if they don’t specifically graph and describe it that way.

Conclusions on Secular Bear Markets

The current secular bear market has lasted a long time. It’s reasonable that investors want to return to a secular bull market environment (a sentiment that we certainly sympathize with), but the reality is that the level of stock market valuation (i.e., P/E) is not low enough to provide the lift to returns that drives secular bull markets. As a matter of fact, P/E is at or above the typical starting level for a secular bear market.

The current situation is not the result of P/E hibernation over the past 15 years. P/E has declined by nearly the same number of points as it has historically in a typical secular bear. This secular bear, however, started at dramatically higher levels as a result of the late 1990s bubble. The market’s work of the past 15 years has been to deflate the excesses that preceded it.

It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that it will take longer for this secular bear to unwind than previous secular bear markets required. We started this secular cycle with a very long way to go. We should actually be glad that we are nowhere near the area that would denote the beginning of a new secular bull market, because the absolute price of the stock market would be devastating to pensions institutions and all of our portfolios.

It is much better for earnings and overall growth to supply the “oomph” in the P/E ratio. Of course that’s a much slower process, especially when GDP growth is in a “Muddle Through” mode.

The passage of time and other factors have led some very smart and respected people to hope for, and then posit, a new secular bull. Unfortunately, the stock market is not positioned to deliver above-average returns over an extended period.

Going forward, there are three scenarios. We could repeat the secular bubble of the late 1990s, yet that seems highly unlikely. We could enter an unprecedented era of high, flat P/E. If so, investors need to have a rational expectation for somewhere around 5% total nominal returns. Finally, we could see the current secular bear run the rest of its course, with P/E declining to levels that portend a new secular bull. The unavoidable reality is that the latter scenario means either an extended period of near-zero returns or a shorter period of cumulative losses. The impact of a declining P/E is an offset to returns – the longer it takes to happen, the less dramatic the effect.

We (John and Ed) have enjoyed a great deal of discussion about possible outcomes. John is of the general opinion that with the next recession we will see a move to lower P/E ratios, which will bring us closer to the final end of the secular bear market. Ed acknowledges that this is a possible scenario but is more agnostic as to how we actually get to that lower level. But we both agree that the secular bear market is not over till the fat lady goes on a P/E diet.

(To our foreign readers, that is not a derogatory saying about weight-challenged persons but a cultural reference stemming from our mutual Texas background. Quote: “The opera ain’t over till the fat lady sings!” – Darrell Royal, the legendary football coach at the University of Texas.)

A secular bear market is not a time to retreat from the market; rather it is a time to position portfolios and expectations for such an environment. The result can be solid investment success; achieving this success just takes a lot more work than when we are enjoying the fruitful conditions of a secular bull.

John here. This is the beginning of what will be a series of letters over the next multiple months on equity investing. I’ve done a great deal of research on the topic over the past six months, on the belief that index funds as they are currently structured are going to be systematically and structurally problematic for your future investment needs. In short, we are still using indexes designed in the 1950s to determine the structure of our portfolios in a world that is being continually challenged by changing paradigms. Even if you are a pure long-only traditional investor, you are giving up three points or more annually simply by your index choices. This makes a huge difference over time. And that’s before you even begin to hedge or optimize. Or to drive down fees.

I am coming to the conclusion that we need a complete rethink of how we go about the business of equity investing, not just in the US but globally. But that is the topic for a number of future letters.

Denver, Home Again, Maine, New York, and Boston

Just for the record, since some new readers might not know who Ed Easterling is, let me offer this brief introduction: Ed is the author of Probable Outcomes: Secular Stock Market Insights and the award-winning Unexpected Returns: Understanding Secular Stock Market Cycles. He is currently president of an investment management and research firm. He previously served as an adjunct professor and taught the course on alternative investments and hedge funds for MBA students at SMU in Dallas. Ed publishes provocative research and graphical analyses on the financial markets at www.CrestmontResearch.com.

I flew home on Friday and will find myself in Denver Sunday night, having dinner with Jack Rivkin, who has been named the new CEO of Altegris Investments. We have been having ongoing discussions on a wide variety of topics, as we both search for ways to express our belief that the investment world is going to change dramatically over the next five to ten years. We would like to be part of helping bring that change about rather than being run over by it. We are often led to some very uncomfortable conclusions, but we are determined to get up on our boards and surf the inevitable.

And speaking of Altegris, the videos of the speakers at our conference are (finally!) becoming available for your viewing pleasure. The first two feature two of our most popular speakers, Jeffrey Gundlach and David Rosenberg. If you are a Mauldin Circle member, you can access the videos by going to www.altegris.com to log in to the “members only” area of the Altegris website. Upon login, click on the “SIC 2015” link in the upper-left corner to view the videos and more. If you have forgotten your login information, simply click “Forgot Login?” and your information will be sent to you.

If you are not already a Mauldin Circle member, the good news is that this program is completely free. In order to join, you must, however, be an accredited investor. Please register here to be qualified by my partners at Altegris and added to the subscriber roster. Once you register, an Altegris representative will call you to provide access to the videos and presentations from selected speakers at our 2015 conference.

It has been busy this week, as I’ve tried to pack in a lot of engagements during my last few days here in New York. There were numerous meetings designed to help me do a deep dive into different ways to slice and dice the investment spectrum. I haven’t found any one-stop-shop solutions (surprise, surprise), but I am beginning to see how combining a number of different and new insights might give us a much more effective overall portfolio design. Steve Blumenthal came over from Philadelphia; I had dinner with Gary Shilling last night at his home in Short Hills, NJ; and I was on the radio with Tom Keene and Mike McKee this morning. It is always interesting to be on with Tom and Mike, because no matter how much you have prepared to talk about the topics that they’ll be interested in, they have a knack for broadening the discussion and taking it in an entirely different direction. Which is what makes them one of the best radio teams in America.

It is time to hit the send button, gather my belongings, and head to the airport. I hope you have a great week.

Your constantly searching for a better way analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com