The Real US National Debt Might Be $230 Trillion

- John Mauldin

- |

- March 21, 2019

- |

- Comments

By John Mauldin

Trump has promised to free the US of debt. He pledged to pay all federal debt off in eight years.

But so far, it’s been just talk. Two years into Trump’s presidency, the US national debt has grown by $2 trillion.

The official, on-the-books federal debt is now at $22.1 trillion. $22.1 trillion is the face amount of all outstanding Treasury paper, including so-called “internal” debt.

It comes to about 105% of GDP, and that’s only the federal government.

If you add in state and local debt, that adds another $3.1 trillion—to bring total US government debt to $24.3 trillion (more than 120% of GDP).

Then there’s corporate debt, home mortgages, credit cards, student loans, and more. Add it all together, and total debt is about 330% of GDP, according to the Institute for International Finance (IIF).

We are in hock up to our ears. But the problem is actually worse than that…

We Define Debt Wrong

In describing our debt problem over the past couple of years, I’ve discovered a problem. Many of us define “debt” way too narrowly.

A debt occurs when you receive something now in exchange for a promise to give something back later. It doesn’t have to be cash.

If you borrow your neighbor’s lawn mower and promise to return it next Tuesday, that’s a kind of debt.

You receive something (use of the lawn mower) and agree to repayment terms—in this case, your promise to return it on time and in working order.

Uncle Sam has made too many promises to too many people, with little regard for its future ability to fulfill them. Prime among them are Social Security and Medicare.

These are debt. Worse, some of them are additional debt on top of the obligations we already see on the national balance sheet.

Even worse, entire generations have planned their retirement lives around the government fulfilling those promises. If those promises aren’t met, their lifestyles will be destroyed.

Running Out of Reserves

Both Medicare and Social Security are now in negative cash flow. That means Congress must provide additional cash to pay the promised benefits—and it will only get worse.

The so-called “trust funds” will dry out sooner or later. Last year’s annual trustee report estimated Social Security will run out of reserves in 2034, and the hospitalization part of Medicare will dry up in 2026.

Any time politicians talk about putting a “lock box” around Social Security or Medicare trust funds, they are either highly ignorant or lying.

Worse, the estimates of when the trust funds run out depend on a slew of assumptions. Most of them are too optimistic.

For what it’s worth, the Social Security Administration says it has a $13.2 trillion unfunded liability over the next 75 years. That’s the benefits it expects to pay minus the revenue it expects to receive.

Medicare projections require even more assumptions, but the “official” assumptions put Medicare’s 75-year unfunded liability at $37 trillion. It could be vastly more—or less, if we all get healthier and healthcare costs drop.

My friend Professor Larry Kotlikoff estimates the unfunded liabilities to be closer to $210 trillion. That’s a far cry from the $50 trillion official estimate.

So, at a minimum, we can probably assume Social Security and Medicare are at least another $50 trillion in debt on top of the $22.2 trillion (and growing) on-budget federal debt.

And then you come to the scary part.

Negative Cash Flow

Last year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its 2018 Long-Term Budget Outlook.

Like the Social Security and Medicare trustees, the CBO makes assumptions, so it’s fair to be skeptical of its estimates.

Because the CBO thinks federal spending will grow significantly faster than federal revenue, it foresees debt as a percentage of GDP will likely be 200% of GDP by 2048. But we will hit the wall long before then.

The CBO numbers show that by 2041, Social Security, healthcare spending, and interest payments will consume all federal tax revenue. All of it.

Everything else the government does (including defense) will require going into more debt.

Yes, making that projection requires an assumption about tax revenue, which requires another assumption about GDP. It could be wrong.

But if so, I think it will be wrong and not in our favor because CBO projections don’t include recessions and wars.

You think we’ll get to 2048 without some years of negative GDP growth? I’ll take that bet.

So, take whatever estimates are made about future deficits and debt, and realize they are going to be worse. Kiss your assumptions goodbye.

And we are not talking about some distant future. Those spending projections and massive deficits are going to happen in the 2020s.

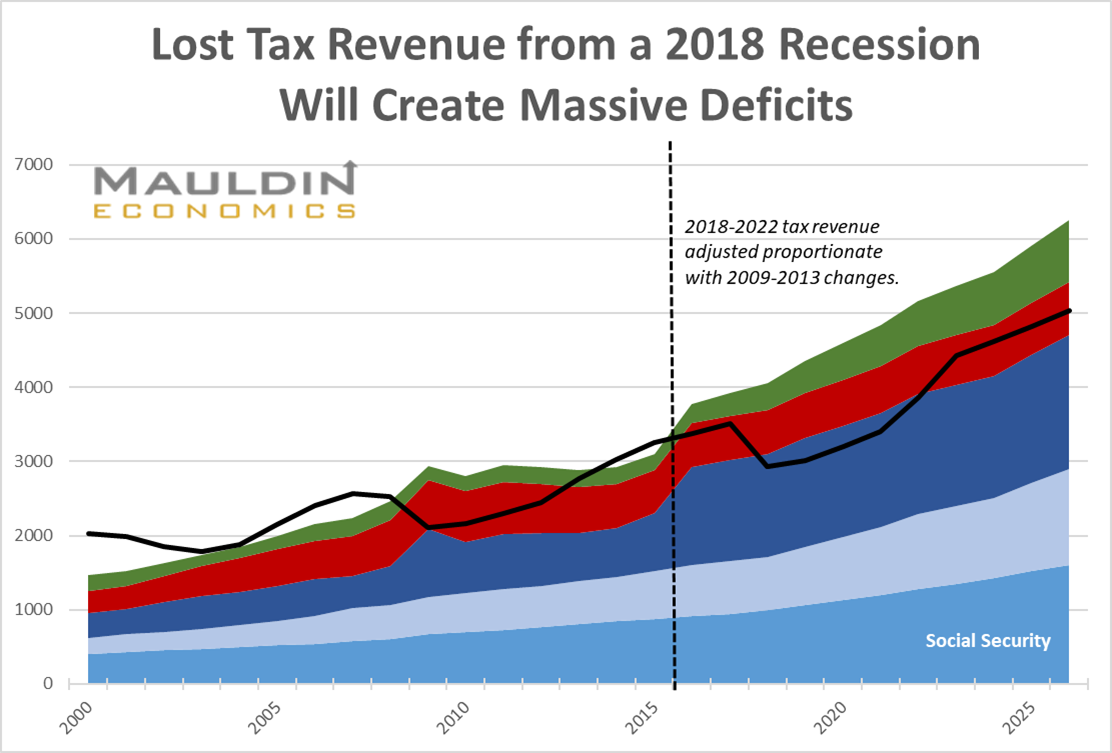

Here is a chart that shows what is likely to happen during the next recession if tax revenue falls to the same degree it did in the last one.

We will have at least a $2 trillion deficit in the next recession, plus a bear market that leaves pensions even more underfunded, and a slower recovery because high debt crowds out future growth. Numerous academic studies back up that statement.

The good news is, none of this is going to happen within the next few years—so we have time to make plans. I’m in the same situation as you are, and I’m already implementing some changes.

Get one of the world’s most widely read investment newsletters… free

Sharp macroeconomic analysis, big market calls, and shrewd predictions are all in a week’s work for visionary thinker and acclaimed financial expert John Mauldin. Since 2001, investors have turned to his Thoughts from the Frontline to be informed about what’s really going on in the economy. Join hundreds of thousands of readers, and get it free in your inbox every week.