Deglobalization Is Already Well Underway—Here Are 4 Technologies That Will Speed It Up

- Patrick Watson

- |

- August 17, 2016

- |

- Comments

BY PATRICK WATSON

If we had to describe the last 50 years of economic history in one word, globalization would be high on the list. Thousands of small, independent economies around the world fused into one nearly seamless whole.

The things we use every day—food, clothing, vehicles, furniture, electronic devices, even the materials that compose our homes—now come from far and wide. We don’t even notice. International trade over vast distances is now so normal that we forget it wasn’t always the case.

But now a reaction to globalization has set in. In cities and towns all over the United States, weekend farmers’ markets have sprung up, selling fruits and vegetables. The main attraction is that they are local.

Eating food grown in your own region is now exotic and unusual. This is in spite of the global diet to which our bodies and minds have grown accustomed.

Globalization ramped up slowly for a century or so before entering a new phase in the 1960s. I was born in 1964, so the explosion of the global economy roughly spans my lifetime. Mine is the first globalized generation. But, if I reach 100, I suspect I will see children of a de-globalized generation.

That’s my theory: We are going full circle. (By the way, join John Mauldin, me, and our senior analyst for a free Q&A session on Aug 23. Find more details here.)

Humanity spent the last 50 years globalizing. Now, thanks to certain technologies, that whole process is reversing. Historians are likely to mark the 2008 financial crisis as the turning point: Peak Globalization.

I don’t say this because I want a de-globalized world. What we want or don’t want is irrelevant. The transition will happen in spite of our desires

Transition will not occur in a linear fashion, however. The point we’ve reached has come in starts, stops, and slowdowns. Reverse globalization too will have its ups and downs. But a new set of technologies will continue to push its progress forward.

Fifty years from now, what new technologies will have proven to be critical? Which of today’s nascent innovations will be revolutionary?

We can only speculate—and John will do plenty of that in his forthcoming book. Meanwhile, I have four candidates. The first one is renewable energy.

Renewable energy

Solar, wind, and other non-fossil-fuel sources have become political footballs. They appear in debates about climate change, government subsidies, environmental regulation, and other subjects that have become politically relevant. That’s unfortunate, because they aren’t inherently political.

They are technologies we should judge on their own terms. Economically speaking, are they better alternatives or not?

“Better” is relative. Fossil fuels are the lowest-cost option in most of the US, in part because we’ve made a huge investment in their infrastructure. We have supertankers, port facilities, pipeline networks, railroads, storage farms, power lines, gasoline pumps, and so on. All of them serve one purpose: moving fuel from the place where it is produced to the place where it is consumed.

This apparatus works surprisingly well, considering that it hasn’t advanced a great deal in many decades. It also points to the great weakness of fossil fuels: We must move them in order to use them. Transporting fuel to wherever it is needed (and keeping adequate amounts available at all times) is expensive and inefficient.

Now, think for a minute about the solar alternative. Today’s technology lets you place solar panels on your roof to power your home. Storage batteries can be used to keep the lights and air conditioning on at night. Solar panels can recharge the electric vehicle you drive to work and back.

All that is possible right now. If you care to spend the money, you can probably go completely off the grid without changing your lifestyle much. That is especially true in the sunny southwestern states, Florida, and Hawaii. Few people quit the grid entirely because to do so is still expensive. That won’t always be the case. Prices are falling fast.

The equation is quite different in emerging-market nations near the equator. Decentralized, renewable energy sources are more cost-effective than fossil fuels right now in countries that don’t already have a well-developed energy infrastructure. Much of Africa will never have an electric grid like ours because it will never need one.

A world economy in which we don’t have to transport fossil fuels back and forth will look different.

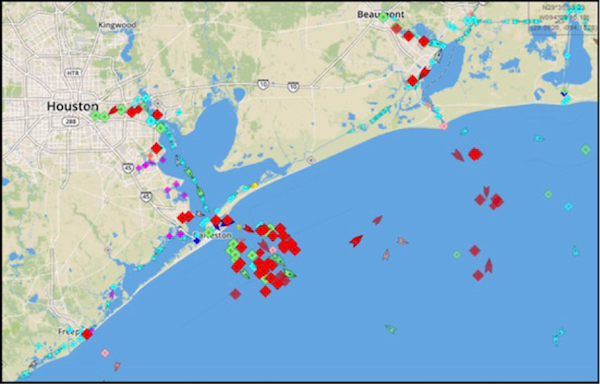

See all the red boxes and arrows on this Houston/Galveston map, via MarineTraffic.com? Those are oil, gas, and chemical tankers. The diamond-shaped ones are anchored, waiting their turn to load or unload.

The map depicts globalization in action.

Get rid of fossil fuels and none of these ships will have to go anywhere. They won’t consume fuel just to move fuel. They won’t sink and make a mess, and they won’t be terrorist targets. Our navy will not need to guard choke points like the Strait of Hormuz. OPEC will become irrelevant.

That world is possible already, and it is getting increasingly practical. A shift to renewables will probably happen even without government subsidies. In fact, I would like to see subsidies eliminated now. They do more to hold up progress than to encourage it.

Fossil fuels won’t go away completely. They’ll remain necessary in niche markets and applications. Nevertheless, I think the economic benefit of harvesting energy near the end user will grow more apparent every year.

In time, energy will cease to be an international concern and become a purely local matter. That facet of globalization will just fade away. Cheap, abundant energy will be as normal as the corner gas station is now.

Additive manufacturing (3D printing)

As John noted in last week’s letter, “The Trouble with Trade,” until recently there were two categories of imported goods. One is expensive, high-quality luxury products: sports cars, wine, fine cheeses, and chocolates. The other is a cheap, low-quality product made mostly in developing countries. Japanese cars weren’t a US status symbol in the 1960s or 1970s.

What do Americans think about imported goods now? We rarely think about them at all, even though we buy them every day. Globalization both raised the quality of foreign-made products and made them unremarkable.

Globalized manufacturing also had a dark side. Manufacturing jobs left the United States as companies moved production offshore. On the other end, gaining those jobs was a mixed blessing for developing countries. Millions of people emerged from deep poverty, but their cultures changed, and rampant, unregulated growth damaged the environment.

More importantly, all these new goods had to find their way from the factory to the buyer. Now, entire shiploads of containers stuffed with shrink-wrapped plastic doodads arrive in US ports every day. They have to be unloaded, sorted, and moved by truck or train to their destination. The logistics chains that do this are organizational miracles, but they consume valuable resources and time.

We wouldn’t need this massive apparatus if it were cost-effective to produce finished goods in small quantities near the final buyer. 3-D printing technology is doing exactly that. Commercial-scale “additive manufacturing” uses a wide variety of materials to make both simple and complex objects.

Additive manufacturing’s key advantage is its flexibility. The same equipment can make completely different products with just a software update and minor retooling.

This capacity opens up a world of possibilities. Instead of specialized factories producing mass quantities of the same thing, local manufacturing centers can produce only the quantity of products or parts needed in the local area.

Moreover, local manufacturing will enable much greater customization to fit local needs. Freed from a global process that forces them to sell monotonous, widely marketed goods, retail stores could use local manufacturers to produce exactly what local buyers want.

Will local manufacturing completely replace global supply chains? No, but it can still make a huge difference by reducing freight traffic. Consumers will have higher-quality goods at the same or lower prices, and the environment will be cleaner.

Today’s just-in-time logistics systems have already reduced inventory levels and contributed to broad deflationary trends. Localized manufacturing should accelerate this shift even further.

Instead of holding finished products in inventory, manufacturers will store raw materials: plastics, metals, minerals, wood, etc. Trade in finished goods will occur locally, in close proximity to end users.

Virtual reality

Communications technology was supposed to reduce the need for travel. Yet, even with videoconferencing now widely available, globalized business professionals fly more than ever. Why?

One reason is that communications technology is still primitive. We can sit in front of a monitor across from another person in front of their monitor. We can see each other, hear each other, and view documents together. All this is wonderful, but it’s still a far cry from face-to-face interaction.

The technology of virtual reality and augmented reality promises to fill this gap. Right now, we can wear special devices and enter startlingly realistic fantasy worlds.

The potential for entertainment and gaming is obvious. The suddenly and immensely popular Pokémon Go game is a form of augmented reality. People love it, but the more common VR/AR use may turn out to be routine for business meetings.

Walk through any airport and the “road warriors” are easy to spot. They’re veteran travelers like John, who jet between major world cities so they can walk into a room and talk to people. They may spend more time going to and from meetings than they spend actually meeting. This is woefully inefficient.

With advanced VR/AR technology, people in different countries will be able to “meet” in a virtual conference room with the full sense of being physically together. Having access to subtle cues—facial expressions, tones of voice, sideways glances—will make these meetings seem almost real.

Something like the fabled Star Trek “holodeck” is decades away, but many road warriors would be happy to get 90% of the way there. Eliminating wasted travel time might easily double or triple their productivity.

VR/AR will let businesses operate efficiently without physical proximity to each other. The vast air transportation infrastructure, and all the energy and resources that go into it will become less critical and will ultimately shrink. Meanwhile, workers and businesses will become more “present” within their local communities simply by spending more time at home.

Indoor agriculture

Few sectors were more changed by globalization than agriculture. The US depends on low-wage, labor-intensive overseas farms for many important foods. Meanwhile, exports from our hyper-efficient grain producers feed millions of people in other countries.

As a result, consumers can now enjoy all kinds of non-native foods no matter where they live. If you are in Alaska, and you like bananas, you can have them. The agricultural supply chain will grow them in Central America and bring them to your local store, at a price.

Bananas in Alaska are an extreme example, but the same process feeds practically all of us. Buy a hamburger anywhere in the United States and the lettuce on it likely comes from California. Why is this? Because areas of California have soil and weather perfectly suited to growing leafy vegetables.

Bananas come from Central America for the same reason.

If we could re-create Central America indoors, Alaskans could actually grow their own bananas. This would require the regulation of moisture levels, soil quality, temperature, and lighting—all at a cost competitive with the importation of bananas.

The newest LED lighting technology brings this idea closer to reality. Scientists are learning how to deliver light at the intensity, frequency, and duration that optimizes growth. LED lights dramatically reduce the electricity required. Paired with solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources, indoor banana farms are no longer hard to imagine—even in Alaska.

Carry that thought process a little further, and we can conceive of entire cities becoming self-sufficient for much of their fresh food.

Produced locally in converted warehouses and vertical farms, the food would be truly fresh, too. Fruits and vegetables wouldn’t spend days or weeks in transit between farm and city, nor would they need chemical pesticides and preservatives.

This won’t work for everything we eat. Centralized production may still make sense for grains, meats, and some other foodstuffs. Regional production on land around cities will continue to increase, too.

Nonetheless, when this technology reaches maturity, not nearly as much food will be transported around the world. It will grow near the people who eat it. This change will likely be good for our health, but the economic consequences may be even greater.

Early in the game

We’ve seen here that technology trends will nudge the world economy away from global integration and back toward local production and investment. Without container ships, jetliners, satellites, and mutual funds, globalization would have unfolded quite differently—and possibly not at all.

Now, alternative energy sources, additive manufacturing, virtual and augmented reality communications, and sophisticated local food-production systems will take us back in the direction of regionalization and localization. Hopefully, this will help to level the economic playing field for people worldwide.

Technology isn’t the only factor, though. Much depends on central bank decisions, international trade agreements, electoral politics, and geopolitical factors.

That said, technological change is implacable. Useful innovations rarely disappear once they’re invented. They can be suppressed or delayed but not eliminated. The globalized economy based on shipping stuff back and forth will make less and less sense as the technologies described here continue to mature.

The political debate over manufacturing jobs misses the point. Manufacturing is already coming back to the US, as are manufacturing jobs—but not in the numbers that once existed. Additive and robotic manufacturing technology will raise productivity far faster than humans can manage to do, and humans will be displaced.

Last week, John quoted General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt saying that “wage arbitrage” is over. Robots do not care where you install them. They cost about the same and work at equal speed no matter where they are.

Robotics will greatly reduce the incentive to make goods far from the end user simply to save on labor costs. The new incentive will be to produce in proximity to the customer. This will allow faster and greater customization.

Technology is changing the foundational principles of globalization. That which loses its foundation eventually disappears—though its demise can take a long time. We are still very early in this megatrend.

A Glimpse of the Future in Aug. 23 Q&A Session with John Mauldin

If you wonder what the future might hold for the US and global economies and stock markets, get answers in the free Q&A session “When the Future Becomes Today” with John Mauldin and his colleagues Patrick Watson and Robert Ross, on Aug. 23, 2:00 PM EDT. Click here to register for the call and to submit your questions.