Then you spot the glaring mistake that is now too late to correct… and you want to slap yourself.

I had that feeling soon after we published last week’s Connecting the Dots. In trying to explain supply and demand, I twisted some words and it all came out backwards.

Then the real fun started.

I hoped for a minute no one would notice. No such luck. Over and over, readers reached out in every possible way to tell me how wrong I was. The barrage went on for hours and I had nowhere to hide.

Worse, it was purely my own fault. Our editing and proofreading team did their jobs flawlessly. I’m the one who decided to “fix” that paragraph right before production. Bad idea.

So, I apologize if the article confused you. I also thank everyone who pointed out my mistake. As painful as it was, you were right to hold me accountable. We’ve corrected the article’s web version.

On the plus side…

This experience reminded me how important words are and how easily we can misuse them. Words can either enlighten or obfuscate. Sometimes people do what I did, not by mistake, but because they want to confuse the reader.

That should outrage every nonfiction writer. When I saw an example later in the week, it gave me the idea for today’s story.

Masters of Doublespeak

Corporate executives are masters of doublespeak. Some are better than others, but they all learn how to spin words in the desired direction. Dial into the conference call following a bad earnings release, and you’ll hear what I mean.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle are even more adept at this sort of thing.

Here’s an example. You know those people from other countries who enter the US without permission? Republicans call them “illegal aliens.” Democrats call them “undocumented workers.” Both terms identify the same group, but have vastly different connotations.

Taxable Confusion

I spent most of last week working with John Mauldin to explore the “border adjustment” tax reform idea. He wrote about it in Thoughts from the Frontline.

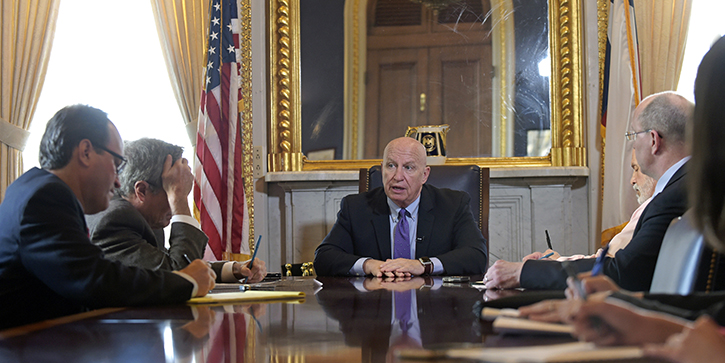

We had a conference call with experts from the House Ways and Means Committee, including the committee’s chairman, Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Texas). They were very kind and tried to help us understand their proposal.

Here is the problem, as the House describes it in a fact sheet.

Under our current broken tax code, U.S. companies pay a tax when exporting products, but not when they import products. To avoid paying that tax on exports, U.S. companies move jobs, research, and headquarters overseas.

This sounds terrible. Taxing exports makes no sense at all. We should stop it at once.

Just one problem: That tax does not exist. The United States does not tax exports and never has.

Constitutional Clarity

Although we have had to amend the US Constitution a few times, for the most part it has withstood the test of time. The Framers left us a document of remarkable clarity.

Article 1 defines how the legislative branch works—and Section 9 is a list of things Congress can’t do. It includes this:

“No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.”

The Constitution prohibits the federal government from taxing exports. They can’t do it, period. Court rulings over the years make this very clear, as you can read in this analysis from the Congressional Research Service.

Since that’s the case, what is this “tax on exports” that Rep. Brady’s committee wants to kill?

The fact sheet I quoted isn’t the only place they use that language. The “Better Way” policy paper says this:

Our high corporate rate, our outdated worldwide tax system, and our origin-basis system that taxes exports have created a perfect storm that has encouraged so many businesses to move their headquarters overseas.

Rep. Brady himself used it in a January 24 speech to the US Chamber of Commerce.

“[F]or the first time in our nation’s history, we will finally end the ‘Made in America’ taxon US exports.”

So if such a tax on exports actually existed, someone who had to pay it would have sued, and the federal courts would have tossed it out. Taxing exports is clearly unconstitutional.

What’s going on here?

The Real Story

Last week, I asked the House Ways and Means Committee staff if they could clarify these statements. I was told they would get back to me. They didn’t. So I can only speculate.

One clue might be in this Reuters news story.

Large multinational corporations are very eager to see this tax reform pass. They must see some advantage in it for them. But if they aren’t paying taxes on their exports, what’s the advantage?

Here’s my guess.

When Rep. Brady and others talk about a “tax on exports,” what they really mean is the practice of taxing US companies on all of their income, wherever in the world they earn it.

I admit that’s a problematic policy, and Congress should change it... but it’s not a tax on exports.

The main beneficiaries of such a change would be large US companies that own factories in other countries. It would do little for small businesses that build their products in the US and ship them to foreign buyers.

By falsely claiming that the US has a “tax on exports,” border adjustment proponents make the problem sound broader than it is. It’s a way to get support from people who aren’t tuned in to the details, aka most Americans.

This kind of doubletalk is what Donald Trump meant when he spoke of “draining the swamp.” It clearly isn’t drained yet.

Possibly, that’s why the president seems skeptical of the border adjustment plan. He once described it as “too complicated.” He knows complexity is a good way to hide things.

But maybe I am reading this wrong. If you are a tax expert who can shed some light here, please contact me. I’ll follow up in a future column.

There’s a lot to like in the “Better Way” tax reform plan. It’s more than just the border adjustment. But if it’s really so great, why stretch the truth to describe it?

Seeing this, I have to wonder what else is in there, and whom the plan’s designers really want to help.

See you at the top,