The “Golden Watch era” is dead (and other disruption principles)

- Chris Wood

- |

- January 2, 2023

- |

- Comments

This article appears courtesy of RiskHedge.

The key to making money from disruptive megatrends... what we can learn from famous astronomer Carl Sagan... why we get our boots on the ground... and why the “Golden Watch era” is dead...

Editor’s note: Thanks for following along in our special holiday series on how to become a great disruption investor. In our first two essays, chief investment officer Chris Wood showed you specific traits the world’s top disruptor stocks share. Today’s final installment is about the right mindset needed to succeed as a disruption investor. As you’ll see, there are four principles to understand. Print these out and keep them close by as we enter 2023:

***

- Great disruption investors know timing trumps all.

Disruptors invent the future.

For example, Amazon created the online marketplace.

Netflix pioneered video streaming.

And Apple is the main reason 85% of Americans have a smartphone.

Disruptors figure out how to accomplish things that have never been done before.

This often leads to big stock market profits. But it can also lead to irrational excitement. And irrational excitement can lead to dangerous situations in the stock market.

You see, investors are emotional creatures. They naturally get excited about big new breakthroughs. Sometimes they get carried away with dreams of riches. Their imaginations run wild, and they can bid disruptive stocks up to the moon.

This makes disruptor stocks prone to hype and wild exaggeration.

Consider Webvan.

In the mid-’90s, startup online grocer Webvan promised to drop your groceries on your front porch within 30 minutes of ordering. Investors drooled over the idea it would claim a big share of America’s colossal $1.5-trillion grocery market. Overeager buyers caused Webvan’s stock price to leap 65% on the day of its IPO.

But it turned out to be a complete disaster. Grocer margins were already razor thin then.

Add in delivery costs—trucks, drivers, fuel—and Webvan lost money on every transaction.

Webvan shut its doors for good in 2001 and donated all its remaining food to a food bank.

And shareholders lost all their money.

As disruption investors, we must always remember timing is key for making money from disruptive megatrends.

As a rule of thumb, when you see folks getting overly excited about a company or trend, be skeptical. And be patient. There’s a good chance it will crash, and you’ll get the chance to buy for pennies after the overeager masses get burned.

- Great disruption investors see domino effects.

The famous astronomer Carl Sagan said, “It was easy to predict mass car ownership but hard to predict Walmart.”

What Sagan meant was… it was obvious in the ’30s and ’40s that cars were the future.

You could see all the signs. The technology was constantly improving. Cars were getting safer and safer. The cost to buy one was plunging.

And so, it wasn’t all that hard to foresee that car ownership would eventually explode, as it did in the 1950s.

But it was much harder to predict the domino effects of mass car ownership.

One of which was the incredible success of Walmart (WMT).

You see, before every family owned a car, grocery stores usually occupied the center of town. They had to be located where people could access them easily.

Mass car ownership changed all that.

Walmart’s strategy was to open “big box” stores on the outskirts of towns where land and rent were cheaper. Its sales exploded 27X from 1965 to 1975 as more and more people drove to its stores.

Walmart’s stock trounced the S&P 500 by more than 50X during the 1970s.

A more recent example is how the rollout of 4G around 2011 helped boost Netflix from a struggling business into a world-beater.

As you likely know, Netflix began as an online DVD rental service. It mailed movies to customers in little paper sleeves.

The problem? Postage costs were crippling. By 2010, Netflix’s shipping fees hit an absurd $600 million.

Because it was coughing up huge sums of money to the US Postal Service, Netflix was losing money on every movie it rented out.

Netflix had toyed with the idea of offering movies online. But in the mid-2000s, internet speeds were too slow.

4G changed the game for good. For the first time ever, Netflix could reliably deliver content to customers over the internet anywhere through cell coverage.

From 1998–2010, Netflix added 20 million subscribers. That’s not bad. But it’s nothing compared to the 120 million it would add over the next eight years.

And more important, its stock leapt 2,800% in the years after it launched its online streaming service.

- Great disruption investors conduct “boots-on-the-ground” research.

If there’s one factor that gives my team an edge, it’s that we do tons of boots-on-the-ground research.

We travel around the world to meet industry experts, attend conferences, and investigate the latest disruptive trends ourselves.

We’ve had dinner with hedge fund managers who control billions of dollars, talked business with Fortune 500 executives in their own boardrooms, traveled around the world to meet with digital money experts, and regularly talked with America’s top private equity strategists.

Great disruption investors know you’ll learn more from conducting boots-on-the-ground research than you ever will sitting behind a desk.

Our network often alerts us to little-known disruptive trends months or years before the average investor catches on.

For example, in early 2013, chief analyst Stephen McBride met with an investor friend who had just bought some bitcoin (BTC).

Keep in mind, bitcoin was selling for around $90 at the time. And nobody but outcasts in the dark corners of the internet was talking about it.

Stephen’s friend explained what it was all about—and convinced him to buy a small stake. As you probably know, bitcoin went on an incredible run and, despite the recent selloff, is still selling for around $17,000 today.

- Great disruption investors know the “Golden Watch” era is dead.

It would be nice to invest like your father or grandfather did.

You buy stock in well-run, financially stable businesses... You hold it for 30 years and reinvest the dividends every quarter... And you watch your money compound.

For most of the 1900s, investors built lasting wealth this way.

I call this bygone time the “Golden Watch” era. Back then, many folks worked at the same company their whole lives. If you worked hard and showed loyalty, you could reasonably expect good pay, a pension, and a gold watch when you retired.

Like it or not, the world doesn’t work this way anymore. Things are changing too fast, both in the business world and the stock market.

As I mentioned, since 2000, half of all Fortune 500 companies have either gone bankrupt, been acquired, or ceased to exist.

And over the past six decades, the average life span of an S&P 500 company has plunged from 58 years to 18 years.

Even some of America’s most rock-solid, longest-lasting companies are struggling to stay afloat today. Consider 150-year-old Kraft Heinz. Its stock has been more than cut in half over the past five years as Americans have turned away from packaged foods.

At the same time, disruptive innovations are reaching “critical mass” at a faster rate than ever.

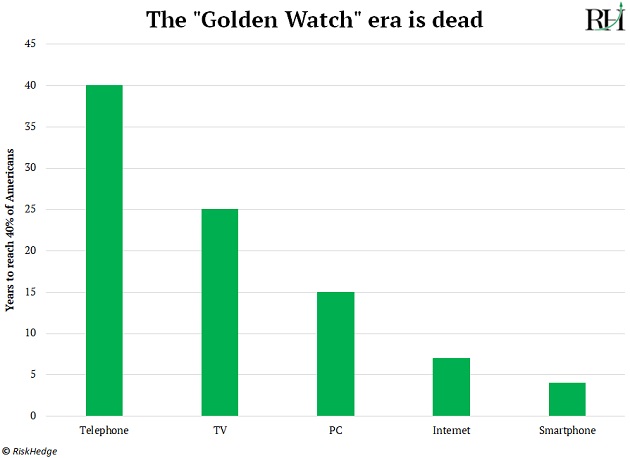

For example, it took the landline phone roughly 40 years to hit 40% penetration in America… TV hit the same milestone in 25 years… PCs took around 15 years to reach a similar proportion. The internet did it in under seven years. And smartphones less than four years.

It’s not an exaggeration to say now is the best time in history to be a disruption investor. And now, you have the right “tools” at your disposal to get started. But if you’d prefer someone like me to guide you, discover more about a risk-free trial to Disruption Investor—including my latest briefing on the Chip Wars—here.

I hope you enjoyed the series, and I look forward to sharing new ideas in the RiskHedge Report soon.

Chris Wood

Chief Investment Officer, RiskHedge

|

This article appears courtesy of RH Research LLC. RiskHedge publishes investment research and is independent of Mauldin Economics. Mauldin Economics may earn an affiliate commission from purchases you make at RiskHedge.com