Do Trade Deficits Matter?

-

John Mauldin

John Mauldin

- |

- March 28, 2025

- |

- Comments

- |

- View PDF

Financial market news has seemingly become all tariffs, all the time. The president’s plan, whatever it is, seems to spring from his belief that trade deficits are bad and must be eliminated. Tariffs are just a means to that end.

I have a somewhat different view. I think the US trade deficit, in itself, is neither good nor bad. It’s the natural result of our position in the global economic order and it has both positive and a few negative aspects.

At the same time, it’s also important for the US (or any other country) to have some degree of self-sufficiency, and to support its own workers and manufacturers. But different segments of the economy require different approaches. Tariffs may be the right answer in some (fewer than you think) situations, but every policy solution has trade-offs.

Juggling all this is hideously complicated. That’s why trade agreements take years to negotiate. Today I’ll try to cut through some of this fog and look at why the US has a trade deficit. As you’ll see, it is a built-in, necessary feature of our money. Plus, it is time to start watching for a recession. Let’s jump in.

A Deficit Powerhouse

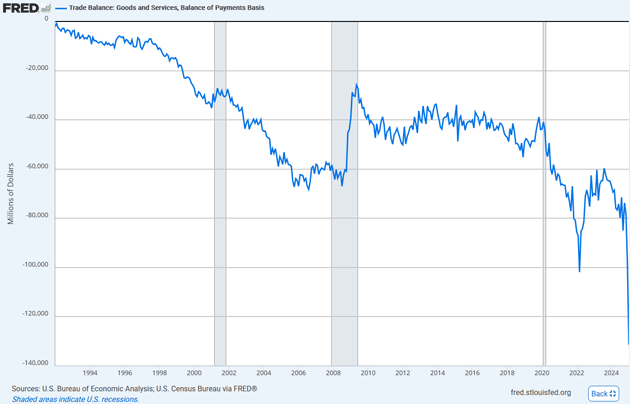

Let’s start with some data. The US buys a lot more “stuff” from the rest of the world than the rest of the world buys from the US. The difference is called the trade deficit, and we have had one almost every year since the 1970s. The trade deficit tends to shrink a little bit when consumer spending drops during recessions, but we have not had a significant trade surplus in many decades.

Source: FRED

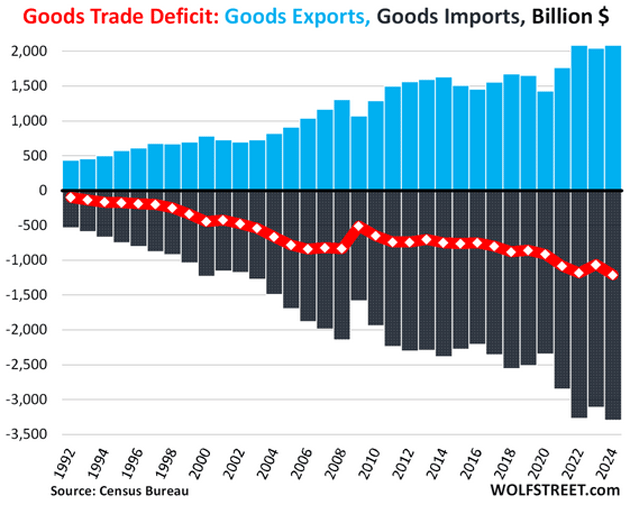

However, it is not the case that US exports are falling. They have actually grown quite a lot. Here’s another chart showing trade in goods. The blue bars are US exports, the black bars are imports, and the red line is the difference, i.e. the goods trade deficit.

Source: Wolf Richter

We export a lot of goods—over $2 trillion worth in 2024. This amount has grown almost every year, making the US an export powerhouse by any definition. The deficit exists only because our imports have grown faster than exports.

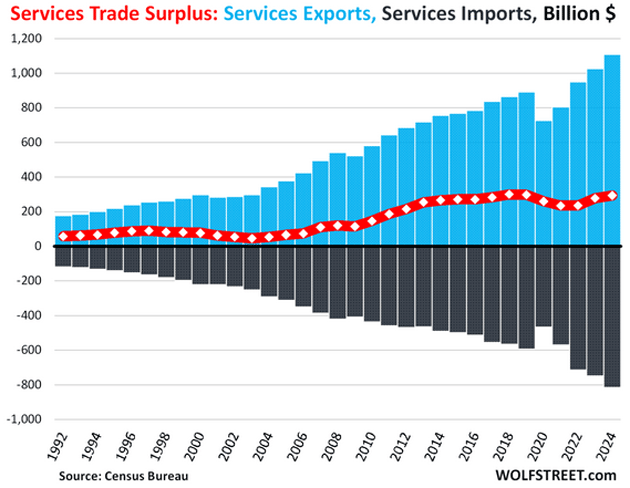

If you look at services rather than goods, the US exports more than we import. This has serious implications if we get into a tit-for-tat trade war. Do we really want Europe and the rest of the world to put tariffs on our services as some now threaten? Think Smoot-Hawley. $1 trillion in service exports is a big deal and we don’t want to screw with it.

Source: Wolf Richter

Combining goods and services shows the US runs an overall trade deficit, but we are still a major exporter—more so in services than goods. This is, to use the classic term, our “comparative advantage.” American companies and workers are good at making nontangible things: software, movies, TV shows, music, and all kinds of business services. The world wants these things and happily buys them from us. Everyone wins as long as it is voluntary.

The process looks like this: We buy stuff from foreigners and give them our dollars. We sell stuff to foreigners and dollars come back. Sometimes more, sometimes less, but the flow never stops. The speed of that flow helps drive exchange rates up and down.

This is why trade policy and currency values are so closely linked. To understand trade, you have to understand money.

Exorbitant Burden

What is money? The simplest definition I know: Money is the most liquid asset, which becomes the medium of exchange because it is widely owned and recognized.

Most sovereign states issue their own currencies, but among those it’s normal for one currency to reign supreme over others. We call this the “global reserve currency” and since 1944 it has been the US dollar. Central banks hold dollars in reserve. Most international transactions settle in dollars. As a result, the non-US world needs a lot of dollars. It is the grease that keeps the global economy turning.

This means the US must constantly export more dollars to meet world demand. This demand for our currency makes it stronger, which in turn makes imports cheaper and exports more expensive. This has been called an “exorbitant privilege” but in some ways it is also a burden. Americans are incentivized to save less money and spend more of it on imported goods.

Our trade deficit is really just a side effect of having the reserve currency. If we were to somehow start running a trade surplus, the rest of the world would become starved for dollars. That would have side effects, too. For one, the dollar would strengthen sharply enough to make our exports unaffordable to others. That wouldn’t be good for American manufacturers and their workers. Moreover, if this persisted then some other currency would take on the reserve role. I assume that’s not what President Trump wants, but it is where his zero-sum trade policy would ultimately lead.

There’s a better way to think about all this. The US imports goods and exports an equal amount of dollars. The dollar is our top export. We can make them cheaply and trade them for all kinds of other useful things on very attractive terms.

|

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

However, this short-term advantage can also produce long-term problems. The monetary policy that keeps trade flowing makes the US a permanent debtor. Overseas it does the opposite, producing excess savings. Both cause imbalances that only get worse with time.

Triffin’s Dilemma

Okay, pay attention class! (which I hope includes a few administration figures!) Summarizing from Investopedia, which is the best summary of a complex subject.

“In October 1959, a Yale professor sat in front of Congress' Joint Economic Committee and calmly announced that the Bretton Woods system was doomed. The dollar could not survive as the world's reserve currency without requiring the United States to run ever-growing deficits. This dismal scientist was Belgium-born Robert Triffin, and he was right. The Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, and today the dollar's role as the reserve currency has the United States running the largest current account deficit in the world.”

Triffin also predicted the collapse of the gold system. He missed a few other things but in general he was right.

If you have the privilege of being the world’s reserve currency, and you really, really, really want to keep that privilege, you must do what my friend Paul McCulley says: act responsibly irresponsible. You must inject your currency into the global system at size. Today that means many trillions of dollars. You are required to run a deficit.

The simple fact is that if we stop running deficits, we will eventually lose the ability to be the world’s reserve currency. That’s math, not policy.

Global trade is not a zero-sum game if you’re the world’s reserve currency. Yes, if you’re a Latin American country or any of 90% of the rest of the world, you need to roughly balance your trade or your currency is going to devalue. That reduces the buying power of your citizens and creates inflation.

Which brings us to 19th-century British economist David Ricardo and his theory of comparative advantage. It says countries can benefit from trading with each other by making the things they are best at making, while importing the things they are not as good at making. This theory is based on the idea that every country has different cost structures and opportunity costs (costs in terms of other goods given up). Focusing on your strengths lets you produce more efficiently.

But this also creates a fluctuating currency for every country. It is a natural result of having to work out what the comparative advantage is.

There is a solution, but not a good one. John Maynard Keynes saw the problem and at Bretton Woods proposed a new non-national currency be used as the global reserve. He called it the “bancor.” Thank God they chose the dollar instead, and here we are. (That may have been Keyne’s worst idea.)

Broad-based tariffs aren’t a good solution, either. As I noted above, a persistent US trade surplus would upend the dollar-based trading system. Where that would lead is hard to say but it’s unlikely to be good.

See the dilemma? We want the advantages of free-flowing trade, but we also want to protect domestic producers and workers from foreign competition. Having both is hard—and might cause even more problems.

Hell Freezes Over

As longtime readers know, I disagree with economist Paul Krugman on pretty much everything. But I have to give him credit for a recent post about trade and jobs. He talks about New York City’s once-mighty Garment District, which in 1950 employed 340,000 workers. It is now gone, with clothing now produced mostly in places like China and Bangladesh.

Is this bad? Those New York garment workers were mainly low-paid immigrants toiling in harsh conditions. In Bangladesh, this kind of work is a step up the ladder. Today’s American workers can be more productive in other ways. Bringing that kind of industry back to the US would be a step down, not up.

Yet it’s also true that many American workers are underpaid and overworked, if they are employed at all. How do we help protect their livelihoods from foreign competition? Here’s Krugman.

“But back to t-shirts and sneakers. We definitely shouldn’t be making those for ourselves. But what should we be making instead?

“A free trade purist would answer, whatever the market decides; let private firms figure out what’s profitable to make in America. And even if you aren’t a free trade purist, you have to admit that governments don’t have a great record of picking winners.

“Yet I, like many economists, have come around to the view that we should engage in a limited amount of industrial policy, using subsidies and other tools to promote some industries of the future, especially those involving advanced technology.

“There are two big reasons limited industrial policy is back in vogue.

“One is that it has become increasingly clear that there are important positive spillovers between technology firms. Silicon Valley is more than the sum of the individual companies located south of San Francisco; it’s a kind of industrial ecosystem of shared services, a pool of skilled workers, and exchange of knowledge. If we want America to be competitive in high tech, we need government policies to encourage the formation of these industrial ecosystems.

“The other, grimmer reason we need industrial policy is geopolitics. Circa, say, 2010 not many people worried about how much of the world’s production of advanced semiconductors—which are now crucial to almost everything—was concentrated in Taiwan. Now we know that the age of large-scale warfare isn’t over, and it’s dangerous to rely for crucial products on industrial clusters easily threatened by potential adversaries.”

This is awkward in multiple ways, not least that I’m agreeing with Krugman, but he’s right. Unrestricted “let the market decide” free trade has some intolerable side effects from the US point of view. Government policy that tries to minimize those side effects is necessary and appropriate. One of the few things both parties agree on is that China is a problem.

How government does this is critical, of course. It can easily go wrong. The kind of “industrial policy” Krugman envisions is highly likely to be not what I would want. But we agree on the danger of relying on foreign suppliers for crucial products. And not just defense or technology, but medicines and other necessities.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

The challenge is where to draw these lines. As Krugman says, the government is historically not good at picking winners. I think the Trump administration has admirably identified the problems, but I am less confident in its solutions. It seems the Trump administration is also trying to pick winners. Solyndra, anyone?

My friend David Bahnsen was recently in Washington for meetings at the Treasury Department. David was trying to get some clarity about the major tariff announcements that are supposedly coming on April 2. He didn’t find much. Here’s part of his report. (You should subscribe to his Dividend Café where today he does a deep dive into the effects of tariffs. A must-read.)

“1. I do not believe there is clarity in markets, in the media, or in the public about tariff policy, or what is coming April 2, because I do not think there is clarity in the administration around tariff policy or what is coming April 2.

“2. Everyone involved has done a pretty good job keeping this out of the public eye, but I believe there is a more intense competition of intent, direction, and philosophy between the Commerce Department (Lutnick, USTR Greer, etc.) and the Treasury Department and NEC (Bessent, Hassett) than previously understood. The bad part of that, from my perspective and market’s perspective, is that Commerce is driving the specifics of what is forthcoming April 2.

“3. The Secretary has way, way, way more of a focus on making permanent the 2017 Trump Tax Cuts (TCJA) than I previously believed. I came away last week convinced they possess the intensity of priority for this they ought to have, even as tariffs have dominated the media story (for good reason). This does not mean they will be successful—it is far more complex and challenging than can be expressed here—but Secretary Bessent’s major focus is on what it will take to pull TCJA and new tax cuts over the finish line. This was by far the most encouraging part of my meetings.

“4. If I were a betting man, I would say the following two things about where we go from here:

- “The biggest thing I can see in where all this is going is to a place on April 3 that is no more clear than where we were on April 1. The President will have a lot of discretion as to what sectors, what companies, what rates, what countries, what tariffs, all get done—and I think chaos and Presidential discretion is the likely outcome, not clarity and policy cohesion. I do not say this as a compliment.

- “I do not believe that markets have moved enough to alter the President’s approach to this. I do believe that there is a point at which they do, and that would force him to do something he generally does very well: find an off-ramp and find a way to claim victory. If that market threshold for such an alteration is 20% (i.e., a bear market), it may very well be that regardless of what pivot takes place from there, a recession will become inevitable as a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy.

“There is already talk about the April 2 announcement being less burdensome than previously feared. The administration is already looking for ways to soften impact to farmers (a strange concession, don’t you think?). I didn’t get clarity from Treasury as to what is coming April 2 because they don’t have clarity. This is a wildly uncertain week or two we are going into.”

I agree with David, and I think the lack of clarity reflects the staggering complexity of the challenge. Reaching the desired balance and fairness is a giant game of pick-up sticks. Moving one stick usually disturbs others. Worse, in this game some of the sticks move themselves and others are invisible until you touch them.

The political imperative—move fast before the opposition can react—conflicts with the slow, methodical work that produces lasting solutions. Maybe that kind of effort is underway behind the scenes. But if so, they’re keeping it well hidden.

Recession Risks Rise

One of the most reliable services for the past 40 years has been The Bank Credit Analyst. Their baseline projections say we will be in a recession later in the year. Ed Yardeni has raised his recession risks from 0% and massively bullish to 35%. Big move for Ed. One analyst after another is highlighting recession risks.

I don’t give a great deal of credence to consumer opinion polls, as they can fluctuate dramatically around political beliefs. They are only useful when consumer actions actually reflect their future opinions. And unfortunately, they are beginning to.

Many consumer-facing companies say things are getting soft. The Bank Credit Analyst says 24 of the first 26 retailers providing first-quarter earnings guidance and 29 of the first 31 retailers offering first-quarter revenue guidance lowered their estimates.

Peter Boockvar cites different companies with the same theme. Peter points out that the main drivers of growth in the US economy have been AI capital expenditures, consumer spending from the top wage earners (especially travel and leisure), and government stimulus. Delta has already cut their first-quarter growth. FedEx and Nike are guiding down for the second quarter.

Now, we come to April 2 and the imposition of tariffs. If Trump actually implements the tariffs he has ordered, I believe we will be in recession within 90 days or less. A 25% tariff on foreign automobiles? Many estimates say it will add $10,000 to the average new car price. An extra 25% tariff on China for buying Venezuelan oil, on top of other tariffs? Not good for Walmart nation.

Tariffs on Canada and Mexico? Really? That’s almost like putting tariffs on New York from California or Texas. You can’t just unwind those very integral, complex parts of the economy without massive disruption.

Is China a real problem? Absolutely. We have to deal with it. But the solutions should be targeted and specific, dealing with the actual problems.

|

The Most Important Conference of the Year: The SIC 2025 |

I am hopeful (hope being the operative word) that DOGE can find the $200 billion in waste and fraud that they say is there. Maybe Congress can find another hundred billion dollars or so (I’m looking at you, Defense Department). That’s a good start. We also have to recognize that cutting this means $300 billion (if we are really truly lucky) less stimulus going into the economy. That will leave a mark. Fiscal stimulus does have an economic effect, and taking it away, even though necessary, will have the opposite effect.

The United States has the exorbitant privilege of issuing the world’s reserve currency. We should not be aspiring to bring back low-paying jobs that can be done elsewhere. We need to be moving up the income and productivity scale, using our comparative advantage.

Let’s take Singapore as an example. Lee Kwan Yew took over with Singapore doing the equivalent of T-shirts and assembly of various products. They moved up the manufacturing curve and are now a high-end export machine, trading power, and global financial center. They don’t rely on T-shirts.

Trade deficits for the world’s reserve currency are not a zero-sum game. They are a requirement. If Trump pursues this policy (and I am not certain he will for very long) it will not end well. The markets will not respond positively.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

I’ll just remind you that all recessions are by definition deflationary and are accompanied by bear markets. I believe (with a lot of hope in that belief) that Trump will back off his tariffs when faced with negative outcomes. I really hope that we get “tariff light” next Tuesday, and the announcement will be a nonevent. Then we can move on with some certainty.

Given that with this administration everything seems to change frequently, we will just have to wait and see. Here’s hoping (that hope word again) reality prevails.

Tulsa, Open Heart Surgery, Dallas, DC, and West Palm

We found out yesterday morning that one of my twin daughters (Abbi) will not need a stent but rather triple bypass open heart surgery. I am leaving for Tulsa in a few minutes on the first flight I could catch. When I was young, open heart surgery was front-page news. Today it’s routine, but I still want to be there when my daughter wakes up tomorrow morning.

I will be back in Dallas with Dr. Mike Roizen in a few weeks when we open our first clinic doing Therapeutic Plasma Exchange, followed shortly by clinics in West Palm Beach, Columbia, Maryland (DC), and Dorado, Puerto Rico.

At the end of April, I will be at a longevity conference in Washington, DC. To the extent possible, I will be trying to meet with members of the Alpha Society in my travels.

The letter is already too long, so it is time to hit the send button. You have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on X.

|

Your grateful for modern medical technology analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Put Mauldin Economics to work in your portfolio. Your financial journey is unique, and so are your needs. That's why we suggest the following options to suit your preferences:

-

John’s curated thoughts: John Mauldin and editor Patrick Watson share the best research notes and reports of the week, along with a summary of key takeaways. In a world awash with information, John and Patrick help you find the most important insights of the week, from our network of economists and analysts. Read by over 7,500 members. See the full details here.

-

Income investing: Grow your income portfolio with our dividend investing research service, Yield Shark. Dividend analyst Kelly Green guides readers to income investments with clear suggestions and a portfolio of steady dividend payers. Click here to learn more about Yield Shark.

-

Invest in longevity: Transformative Age delivers proven ways to extend your healthy lifespan, and helps you invest in the world’s most cutting-edge health and biotech companies. See more here.

-

Macro investing: Our flagship investment research service is led by Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino. His thematic approach to investing gives you a portfolio that will benefit from the economy’s most exciting trends—before they are well known. Go here to learn more about Macro Advantage.

Read important disclosures here.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

Tags

Did someone forward this article to you?

Click here to get Thoughts from the Frontline in your inbox every Saturday.

John Mauldin

John Mauldin