The Uncertainty World

-

John Mauldin

John Mauldin

- |

- April 18, 2025

- |

- Comments

- |

- View PDF

Markets don’t like uncertainty. It is a cliché, but for a very good reason. It is more than a truism. In fact, businesses don’t like uncertainty. You and I don’t like uncertainty in our personal lives. When we go to the store, we want to be certain that what we are looking for is there, and at a reasonable price. We want our food orders to be certain. We want our relationships to be certain. In fact, the relationships we value most are the ones in which we feel certain whether it’s personal, business, or investing.

Today we are going to look at some of the uncertainties in our world and then explore some ways to gain a little certainty.

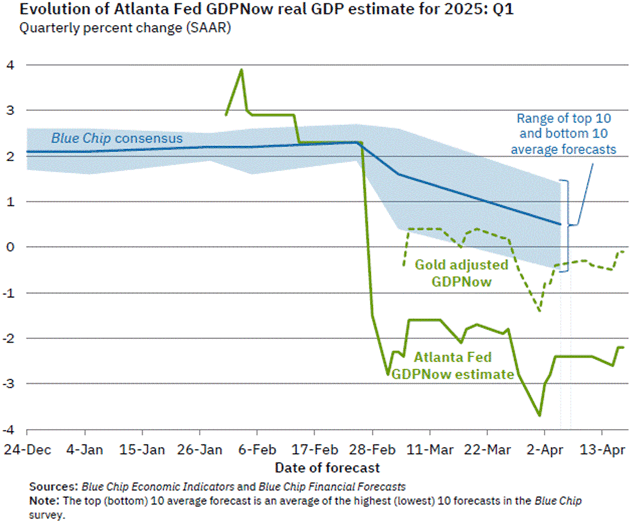

We talked about The Uncertainty Recession recently, and that certainly seems to be the case for the first quarter. We looked at the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate a few weeks ago and it was indicating a first-quarter recession. The latest update for their projection is worth quickly revisiting.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Several comments are in order. First, the Atlanta Fed acknowledges the impact of gold imports on their GDP forecasts. This week I learned (and now you will) about how the Atlanta Fed tracks gold. Turns out it is not straightforward. And that it makes a difference going forward.

I should note that my “edge” in writing this letter is I have fabulous sources of information (and conversations!) that I have developed over the years. Plus, I am part of several group chats and texts with seasoned market experts who regularly comment on data and a wide variety of topics. What I have in addition is my readers who graciously send me information and ideas.

Reader Robert Merrill actually wrote the caretaker of the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model, Pat Higgins, who wrote him back. It turns out there are two sources for importing gold data: the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. According to Mr. Higgins, the Census Bureau’s numbers can be quite different because many gold import bars are classified as finished metal shapes. The BEA classifies them as nonmonetary (for trade purposes) gold. Higgins said that going forward they will likely make the switch to the BEA numbers as they are more accurate for their purpose.

Why does this matter? Right now, you can see that if you use the Census Bureau numbers for gold they would say that the actual projections would only show a slight recession. Presumably, the BEA numbers would show a much deeper downturn.

While the GDPNow can vary widely in the early months, this late in April with no more data to come in it is highly likely Q1 will show negative GDP growth. The data could move either way from their projection. If the final data shows more imports than are currently counted, the downturn will be deeper. BEA will issue three Q1 GDP estimates over the next three months, an initial “advance” number later this month, then two updates. These can change significantly as new data comes in.

I think this recession, if this is the beginning of one, will be different than the typical business cycle recessions we have experienced in the past. Policy uncertainty is causing some businesses to pause expansion plans, unsure of what tariff and other tax policies will prevail 6–12–24 months from now.

Not all the data is negative, though. Consumer spending remains solid. Households and businesses are not overleveraged and still have spending capacity. However, consumer sentiment is down significantly. Normally sentiment is reflected in consumer spending. Why the disconnect?

Because consumers and businesses may be spending more to get ahead of the potential tariffs. Just as high inflation makes consumers spend today to avoid high prices in the future, potential 25% tariffs (and much higher for Chinese goods) have the same effect. In essence, if you know you will need a particular product soon, why not just buy it now?

This is not just speculation on my part. My good friend Lyric Hughes Hale of Econvue sent me this note:

“As a tidal wave of tariffs rolls in around the world, weak consumer confidence numbers have sparked fears of a coming recession, driven by fears of falling consumption. At least in the US however, this is not historically true. Americans are born and bred to consume, and paradoxically, anxiety only seems to increase their propensity to spend. The interplay between financial conditions and consumer behavior is complex.

This is a feature of a psychological phenomenon called catastrophic thinking. In February of 2025, a survey by Creditcards.com found the following:

-

1 in 5 Americans are buying more than usual, most driven by Trump’s tariffs

-

3 in 10 Americans are purchasing items in preparation for another pandemic

-

42% of Americans are or will start stockpiling items, mainly food and toilet paper

-

1 in 4 Americans have made large purchases since November in fear of Trump’s tariffs

-

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

1 in 5 Americans say they are “doom spending”—purchasing items excessively or impulsively in response to fears or anxiety about future events

-

23% of Americans expect to worsen or go into credit card debt this year

“…after 9/11, confidence fell by 25%, but spending only fell by 1.3% and rebounded within a month. This pattern repeated during Covid, when direct fiscal stimulus added fuel to the fire, driving retail spending to all-time highs. While culturally, Chinese consumers react to stress by saving more, US consumers spend more in times of uncertainty as a form of emotional reassurance, a pattern reflected in post-crisis retail surges.”

This becomes even more tricky in terms of forecasting recession. If consumers and businesses are mainly buying imports, it’s negative for GDP. Businesses delaying expansion plans is clearly negative for GDP. But of course, we still see large businesses double down on anything related to artificial intelligence.

Further, Lacy Hunt tells us in his latest essay that: “Five pivotal US economic considerations, including tariffs, monetary policy, fiscal policy, debt overhang, and demographics, are aligning to depress economic growth for the balance of this year and into 2026.” I talked with him about this view, and he will elaborate on it at the SIC.

Slower economic growth means lower tax revenue and higher unemployment and other safety net spending, the opposite of what the Trump administration needs if it wants to reduce the deficit. An actual recession will aggravate the deficit even more.

|

Where Do We Go from Here?

The Trump administration certainly knows that uncertainty is creating negative pressure on the economy. They are clearly trying to reshape the global trading order, but it is, well, uncertain what it will look like when they are finished. Will it be a world of more open and balanced trade? Or a world of trade within silos because tariffs force businesses all over the world to adjust supply chains?

The most important negotiations are the ones that are occurring between China and the US. And yes, those negotiations are happening. It is not clear how they will unfold. Trump is evidently willing to build a wall around China if he does not get what he feels is fair and equitable.

While some think that Beijing has a strong hand, I am more skeptical. Certainly China is a powerhouse, but their system is not market-driven and has misallocated an enormous amount of capital. China relies on the world, and to a great extent the US, to be its consumption driver, as the Chinese save 30 to 40% of their earnings. Yes, many Chinese leaders are very upset, but they have constraints. It is not the best climate for negotiations, but both sides really need to come to the table.

We will have three sessions focused on China at this year’s Strategic Investment Conference and several more where China will be a significant topic. I expect our speakers will know a great deal more in 30 days. (We will have one speaker deeply embedded in China who will present anonymously.) These figures include people who are old China hands, fluent in the language and culture, many with deep connections in the business and government worlds there.

The Trump administration seemingly believes it can resolve the tariff issues in 3 to 6 months, removing the uncertainty currently plaguing the system. They are clearly willing to suffer a recession if need be in order to restructure the global trading system. The removal of uncertainty will certainly spur a great deal of economic activity and growth. If you combine that with scaling back the regulatory deep state, it could produce an environment where manufacturing grows significantly. That seems to be their bet.

My friend Mark Mills will be presenting at the SIC on energy, but he is also an expert on all sorts of government activity. In a recent paper at the Manhattan Institute he noted that “…complying with federal regulations now costs $29,100 for large companies and $50,100 for small firms—per employee, per year. Tomorrow’s large firms start as small ones, and over 90 percent of manufacturers are small firms that account for 40 percent of manufacturing employment.”

Since 2017, there have been 550 major rules costing over $100 million imposed on manufacturing businesses. The total cost of regulations is $80 billion a year. Mark argues with real data that regulations are far more destructive to jobs than technology. Technology in fact creates jobs.

Now think about how much regulation costs Chinese or other foreign manufacturers. And we wonder why US manufacturers have trouble competing! Some regulations are obviously needed, but bureaucrats are incentivized to increase regulations, as it increases their budgets and importance. Or creates opportunities when they go into the private sector. The exact opposite of what is needed. We will see what Trump can do.

The US is still the entrepreneurial center of the world. But China is clearly catching up. We need to remove the impediments that hamper US activity at the same time we are negotiating for fair trade.

Finding Certainty in an Uncertain World

The Strategic Investment Conference starts in three weeks. The conference is focused on helping you navigate through the next few years, as well as giving you a peek into future technology and investment opportunities. The SIC is my personal art form. I painstakingly craft the faculty to give you the widest perspective on the global environment while at the same time giving you specific ideas for your own investment needs. We look at both how the near future will unfold as well as what is coming up in 5–7 years that will literally change our lives. And offer fabulous investment opportunities.

This year we are doing something a little different, in that we are releasing the entire committed speaker roster in advance. When you look at it, you will see names that you know and want to hear from, and you will see names you don’t know, but I can tell you they are likely going to be just as important and perhaps more impactful. This is by far the best faculty that we’ve ever had for SIC. And it isn’t complete! You will notice a few blank spots, as we are holding some spots open for some very well-known speakers. I am also attending a private conference in a few weeks where I hope to convince a few more all-stars to join us. We’ll see.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

This conference has always been focused on investments. This year we will have Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital telling us how he plans to invest in the future. Howard is clearly one of the most successful investors of the last four decades. His quarterly wisdom is a must-read for me. In that same all-star category, Felix Zulauf will appear twice. Sitting in Zürich, Felix gives us a more global view of how the world looks.

Peter Boockvar, Barry Habib, Danielle DiMartino Booth, Jim Bianco, Ed Yardeni, Karen Harris, and Liz Ann Sonders are some of the best data analysts and economic authorities anywhere. Their resumes would take a full letter. If you look at their track records in speaking at past SICs, they have been remarkably on target. They will give you clarity on what is happening in the wide world of economics, investment, housing, and the markets. David Bahnsen will show you his strategy for navigating uncertain times and his track record shows that he excels at it. He will also join us for the final panel.

Of course, Lacy Hunt and David Rosenberg will be back.

|

This Isn’t a Cycle—It’s a RESET. • 30+ expert speakers who have navigated past crises • 32+ in-depth sessions on markets, trade, and global power shifts • Actionable insights to position yourself for what’s ahead |

I mentioned China above. Louis Gave will give his perspective as well as where he thinks money should be allocated today. Lyric Hughes Hale will be joined by China expert Carl Minzner. I have listened to them and we are lucky to have persuaded them to join us. Marko Papic has persuaded @ShanghaiMacro (our anonymous panelist) and Matthew Pines to join him after he presents his view of the global macroeconomic world. He is now a forceful presence in the international conversation and one you don’t want to miss. (His first major presentation in his career was well over 10 years ago at SIC. He blew the audience away and was quickly picked up by a major research firm that was in the audience and the rest is history. At least that’s his story.)

But we have more on geopolitics, as it is clearly impacting the world. George Friedman and Pippa Malmgren will both look at tariffs and the geopolitical realities. Felix Zulauf of course will weigh in as well with his global geopolitical views which impact his investing.

We can all see how technology has shaped our lives. This old dog is finally learning how to incorporate AI into my entire business life. I can tell you it is changing my work and research habits immensely. And we will be looking at AI as Joe Lonsdale interviews the chief technology officer for Palantir. They and other companies like them will be the primary beneficiaries of the move by the Trump administration to update government technology.

(Sidebar: The IRS is notorious for giving wrong answers to people who call in on their “helpline.” The system is that complex. But at its core, it’s just a system of rules. AI could take those rules and answer the questions much more correctly and quickly. And at a fraction of the cost. If AI can take the knowledge from Dr. Mike Roizen on longevity along with massive amounts of research and create a system that can answer any question on longevity (it is in final testing), which is vastly more complex than the IRS code, then why can’t it do it on any number of government databases? We will be asking that question.)

My good friend Lord Matt Ridley, author of The Rational Optimist and the phenomenally important Evolution of Everything, will join us to talk about his research on not just the impact of AI, but where technology is evolving in general. The good news is that you will be able to review it and read the transcript anytime—a benefit available for all SIC presentations when you order your 2025 Virtual Pass.

There are obviously wars going on in the world. Generals are notorious for fighting the last war, but technology is shaping how wars in the future will be won and lost. Stephen McBride will have three (out of dozens) handpicked companies present on how they are reshaping defense technology. The 80% of defense spending that goes to just five large defense companies, often with no competitive bidding? That is going to change. I think we’ll look back in five years and find one of the major shifts under the Trump administration was the shakeup in our military. Counting the cost for intelligence, which we should, we spend over $1 trillion. And you know there is a lot of waste and money misspent on systems of the past. As investors and citizens, we want to know the systems of the future.

Mark Mills will talk to us about the future of energy. I know of no better expert on the entire spectrum of energy in the world than Mark. Energy is critical to our global economy, and Mark will help us skate to where the puck will be.

Mark Halperin and Bruce Mehlman will lay out the political realities for us. Obviously, they’re a great source of uncertainty that we need clarity on. I can’t wait.

I am in a small but active text chat group with David Bahnsen and Renè Aninao. They are just so wired into the Treasury, Defense, and State departments. They meet with the Who’s Who all the time, because they have long-standing relationships with the people you read about in the headlines before they make the headlines. They are sought out for their views. I can’t add you to our text group, but the next best thing is getting them together so you can hear their analysis. It is not always comforting but it is always insightful and revealing. And fun!

The medical field is changing. The Trump administration is shaking up the entire government medical establishment. I have often said that I didn’t want to reform the FDA. I wanted to replace it. I admit it was kind of a glib statement. Now we are seeing some of the impact when that is apparently happening. We will have a panel with Dr. Mehmet Oz, now the administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Robert Redfield, former director for the CDC (fascinating, troubling, and insightful stories around the dinner table about his tenure there) and Dr. Mike Roizen who is consulting with numerous actors in the space. It will be a panel for hard questions.

Like what you're reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

I have asked Martin Gurri to talk with us about how technology is shaping our society, his view on the tension among elites, and how this will play out over the next few years. Note that he predicted a Trump-like figure in 2014 in his foundational book. He has continued his remarkable stream of accurate forecasts looking at the world through the lens of a former CIA information analyst.

In addition to his presentation, he will be on the final panel joined by Felix Zulauf, David Bahnsen, and myself as we analyze how the pressures of the world will evolve into the future.

This is a conference you don’t want to miss. I think this conference will be as important as the ones that we did in 2008–09 and 2020, again in the middle of a great deal of uncertainty. Looking back, those conferences positioned the listeners to take advantage of the inevitable and powerful recoveries. They were not bearish at all, they were looking to the future. Yes, we were in the middle of bear markets but the ends were in sight. There were lots of opportunities talked about that came to pass.

You want to be at this conference. Click on this link and join me and our faculty. The conference starts May 12 and runs every other day for 10 days. Every session is recorded and transcribed and you will have access to the video immediately and transcriptions soon afterward (thanks to AI), so if you miss a session, you can watch it and/or read it at your leisure.

Don’t procrastinate. Register now.

DC, Dallas, and Everywhere

I will be in DC Saturday night and for the next four nights attending a longevity conference and meeting with friends and readers. It will be a busy time. The next week I will be at a private conference for a few days, then the SIC will have me in Puerto Rico for 12 days and I will likely be in Dallas where our new longevity clinic will have been opened, then shortly in West Palm Beach, back in the DC area and of course here in Dorado Beach where we are opening clinics. And we are in negotiations for more. It is a busy time.

I am doing a deep dive into AI and finding that most of my friends already are there. I am picking up tips and amazed at what I can do. I found out that I can take a folder in my inbox that I have been filling with emails for 15 years, click on all the messages and their attachments and it will show up in one PDF document I can then use to train my own personal AI. I am a bit of a pack rat on information. I now kind of regret deleting documents I knew I would never get back to, because they would be useful to have in my “database of everything in my inbox.” And the research I can get? Oh, dear gods. I’ll stop there.

For those of you who asked, Abbi is recovering nicely from her open-heart surgery. And with that, I will hit the send button and wish you a great week!

|

Your ready for SIC to start analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.

Put Mauldin Economics to work in your portfolio. Your financial journey is unique, and so are your needs. That's why we suggest the following options to suit your preferences:

-

John’s curated thoughts: John Mauldin and editor Patrick Watson share the best research notes and reports of the week, along with a summary of key takeaways. In a world awash with information, John and Patrick help you find the most important insights of the week, from our network of economists and analysts. Read by over 7,500 members. See the full details here.

-

Income investing: Grow your income portfolio with our dividend investing research service, Yield Shark. Dividend analyst Kelly Green guides readers to income investments with clear suggestions and a portfolio of steady dividend payers. Click here to learn more about Yield Shark.

-

Invest in longevity: Transformative Age delivers proven ways to extend your healthy lifespan, and helps you invest in the world’s most cutting-edge health and biotech companies. See more here.

-

Macro investing: Our flagship investment research service is led by Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino. His thematic approach to investing gives you a portfolio that will benefit from the economy’s most exciting trends—before they are well known. Go here to learn more about Macro Advantage.

Read important disclosures here.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.

Tags

Did someone forward this article to you?

Click here to get Thoughts from the Frontline in your inbox every Saturday.

John Mauldin

John Mauldin