Thoughts from the Frontline: The Age of Transformation

- Patrick Cox

- |

- June 14, 2014

- |

- Comments

One of the many luxuries that my readers have afforded me over the years is their willingness to allow me to explore a wide variety of topics. Not all writers are so blessed, and their output and responses to it tend to stay focused on specific, often quite narrow topics. While this approach allows them to dig very deep into particular subject matter, it can reduce the total scope of their research, vision, and advice. But don’t get me wrong; these types of letters are very important. I benefit greatly from being a subscriber to a number of letters that give me detailed analysis for which I simply don’t have the time to do the research. There’s just too much going on in the world today for any of us to be an expert in more than a few areas.

I seem to find the most enjoyment and elicit the best response when I try to give my readers the benefit of my broad scope of reading and research as I try to figure out how all the various and sundry pieces of the puzzle fit together. For me, the world is just that: a vast and very complex puzzle. Trying to discern the grand themes and detailed patterns as the very pieces of the puzzle go on changing shape before my eyes is quite a challenge.To try to figure out which puzzle pieces are going to have the most influence and impact in our immediate future, as opposed to languishing in the background, can be a frustrating experience. I often find myself writing about topics (such as a coming subprime crisis or recession) long before they manifest themselves. But I think it is important to see opportunities and problems brewing as far in advance as we can so that we can thoughtfully position ourselves and our portfolios to take advantage.

Today I offer some musings on what I’ve come to think of as the Age of Transformation (which I have been thinking about a lot while in Tuscany). I believe there are multiple and rapidly accelerating changes happening simultaneously (if you can think of 10 years as simultaneously) that are going to transform our social structures, our investment portfolios, and our personal futures. We have had such transformations in the past. The rise of the nation state, the steam engine, electricity, the advent of the social safety net, the personal computer, the internet, and the collapse of communism are just a few of the dozens of profound changes that have transformed the world in which we live.

Therefore, in one sense, these periods of transformation are nothing new. I think the difference today, however, is going to be the simultaneous nature of multiple transformational trends playing out within a very short period of time (relatively speaking) and at an accelerating rate.

It is self-evident that failure to adapt to transformational trends will consign a business or a society to the ash can of history. Our history and business books are littered with thousands of such failures. I think we are entering one of those periods when failing to pay close attention to the changes going on around you could prove decidedly problematical for your portfolio and fatal to your business.

This week we’re going to develop a very high-level perspective on the Age of Transformation. In the coming years we will do a deep dive into various aspects of it, as this letter always has. But I think it will be very helpful for you to understand the larger picture of what is happening so that you can put specific developments into context – and, hopefully, let them work for you rather than against you.

We’re going to explore two broad themes, neither of which will be strange to readers of this letter. The first transformational theme that I see is the emerging failure of multiple major governments around the world to fulfill the promises they have made to their citizens. We have seen these failures at various times in recent years in “developed countries”; and while they may not have impacted the whole world, they were quite traumatic for the citizens involved. I’m thinking, for instance, of Canada and Sweden in the early ’90s. Both ran up enormous debts and had to restructure their social commitments. Talk to people who were involved in making those changes happen, and you can still see some 20 years later how painful that process was. When there are no good choices, someone has to make the hard ones.

I think similar challenges are already developing throughout Europe and in Japan and China, and will probably hit the United States by the end of this decade. While each country will deal with its own crisis differently, these crises are going to severely impact social structures and economies not just nationally but globally. Taken together, I think these emerging developments will be bigger in scope and impact than the credit crisis of 2008.

While each country’s crisis may seemingly have a different cause, the problems stem largely from the inability of governments to pay for promised retirement and health benefits while meeting all the other obligations of government. Whether that inability is due to demographic problems, fiscal irresponsibility, unduly high tax burdens, sclerotic labor laws, or a lack of growth due to bureaucratic restraints, the results will be the same. Debts are going to have to be “rationalized” (an economic euphemism for default), and promises are going to have to be painfully adjusted. The adjustments will not seem fair and will give rise to a great deal of societal Sturm und Drang, but at the end of the process I believe the world will be much better off. Going through the coming period is, however, going to be challenging.

“How did you go bankrupt?” asked Hemingway’s protagonist. “Gradually,” was the answer, “and then all at once.” European governments are going bankrupt gradually, and then we will have that infamous Bang! moment when it seems to happen all at once. Bond markets will rebel, interest rates will skyrocket, and governments will be unable to meet their obligations. Japan is trying to forestall their moment with the most breathtaking quantitative easing scheme in the history of the world, electing to devalue their currency as the primary way to cope. The US has a window of time in which it will still be possible to deal with its problems (and I am hopeful that we can), but without structural reform of our entitlement programs we will go the way of Europe and numerous other countries before us.

The actual path that any of the countries will take (with the exception of Japan, whose path is now clear) is open for boisterous debate, but the longer there is inaction, the more disastrous the remaining available choices will be. If you think the Greek problem is solved (or the Spanish or the Italian or the Portuguese one), you are not paying attention. Greece will clearly default again. The “solutions” have so far produced outright depressions in these countries. What happens when France and Germany are forced to reconcile their own internal and joint imbalances? The adjustment will change consumption patterns and seriously impact the flow of capital and the global flow of goods.

This breaking wave of economic changes will not be the end of the world, of course – one way or another we’ll survive. But how you, your family, and your businesses are positioned to deal with the crisis will have a great deal to do with the manner in which you survive. We are not just cogs in a vast machine turning to powers we cannot control. If we properly prepare, we can do more than merely “survive.” But achieving that means you’re going to have to rely more on your own resources and ingenuity and less on governments. If you find yourself in a position where you are dependent upon the government for your personal situation, you might not be happy. This is not something that is going to happen all of a sudden next week, but it is going to unfold through various stages in various countries; and given the global nature of commerce and finance, as the song says, “There is no place to run and no place to hide.” You will be forced to adjust, either in a thoughtful and premeditated way or in a panicked and frustrated one. You choose.

I should add a note to those of my readers who think, “I don’t have to worry about all this because I am not dependent on Social Security.” Wrong. A significant majority of the retiring generation does depend on Social Security and also on government-controlled healthcare, and their reactions and votes and consumption patterns will have an impact on society. Ditto for France, Germany, Italy, and the rest of Europe. The Japanese have evidently made their choice as to how to deal with their crisis. If you are a Japanese citizen and are not making preparations for a significant change in your national balance sheet and the value of your currency, you have your head in the sand.

There’s no question that the reactions of the various governments as they try to forestall the inevitable and manage the crisis will create turmoil and a great deal of volatility in the markets. We have not seen the last of QE in the US, but Japan is going gangbusters with it, and it is getting fired up in Europe and China.

Most people in most places will attempt to ignore the transformational wave barreling at them. After all, aren’t bond rates in Europe lower than ever? Indeed, French and Spanish bond yields are at their lowest levels since the 1700s, believe it or not. Isn’t the market telling us there isn’t a problem? If Japan is such a problem, shouldn’t the yen be going into the toilet by now? The US deficit is shrinking, and government spending is actually falling. Seems like the problems have all gone away.

But the problems I’m thinking about are not ones that will manifest themselves this week. The markets did not foresee the 2008 credit crisis or the last two recessions or the European crisis, even just a few months before they hit. When the world doesn’t come to an end as predicted (and there were plenty of prognostications of utter doom last decade), we seem to get complacent and ignore the basic arithmetic that you have to have more income than you have expenditures, and to conveniently forget that debt, even at low interest rates, is compounding. And yes, it is possible to grow your way out of the problem – but only if you have real growth. Now, much of the world is structurally challenged in such a way that structural imbalances inhibit growth at the rate necessary to significantly put a dent in swelling debt levels.

The Second Wave of Transformation

Contrasting with this rather negative set of circumstances is the second great transformational theme that I want to explore with you, and that is the far more positive accelerating trend in a vast array of technologies. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that we’re in a race between how much wealth and value and improvement in lifestyles human ingenuity can create versus how much destruction of wealth and lifestyles governments can destroy.

It is a tendency of ours to take our recent past and project it in a linear fashion into the future. That’s the way we are hardwired. And while we all acknowledge that change is happening faster today than it did 20 or 30 years ago, we really don’t expect the pace of change to quicken in the future. The next 20 years, we figure, will more or less unfold as the last 20 years has. Not a chance. That assumption is missing the second derivative of change – the acceleration of the pace of change.

As a thought experiment, let us assume that we were going 40 miles an hour in 1984, and by 2004 we were going 50 miles an hour. But today we’re going 60 miles per hour. It took 20 years to get that additional 10 miles per hour (from 40 to 50) but only 10 years to go from 50 to 60 miles per hour. If we continue to accelerate, we’ll be going 100 miles an hour in another 20 years!

While the impact of the internet and computers is evident, what I’m suggesting is that we are going to see multiple technologies go from deceptively hiding in the background, with the pace of change they promise frustratingly slow, to suddenly taking center stage and becoming disruptive. It will be as if the steam engine and electricity and the automobile and telecommunications all appeared at the same time, after having been developed in the background for many decades.The mobile and wireless internet, artificial intelligence and automation, the internet of things, advanced robotics, autonomous vehicles, advanced energy exploration technology, renewable energy (especially solar energy), advanced materials, the rapidly accelerating biotechnology revolution, nanotechnology, and even electronic currencies (Bitcoin et al.) are all rapidly approaching the “elbows” of their own accelerating curves. Each of these areas is going to go exponential in the next 10 to 20 years.

The change I am contemplating is not simply better phones and electric cars and a few new medical therapies. I think we are in for a radical adjustment to the very mechanisms of production and the very structure of our economic and social life.

Joseph Schumpeter described capitalism as the “perennial gale of creative destruction.” In an excellent essay on creative destruction, W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm lay out the paradox between the demise of old industries and the rise of new ones (emphasis mine):

Schumpeter and the economists who adopt his succinct summary of the free market’s ceaseless churning echo capitalism’s critics in acknowledging that lost jobs, ruined companies, and vanishing industries are inherent parts of the growth system. The saving grace comes from recognizing the good that comes from the turmoil. Over time, societies that allow creative destruction to operate grow more productive and richer; their citizens see the benefits of new and better products, shorter work weeks, better jobs, and higher living standards.

Herein lies the paradox of progress. A society cannot reap the rewards of creative destruction without accepting that some individuals might be worse off, not just in the short term, but perhaps forever. At the same time, attempts to soften the harsher aspects of creative destruction by trying to preserve jobs or protect industries will lead to stagnation and decline, short-circuiting the march of progress. Schumpeter’s enduring term reminds us that capitalism’s pain and gain are inextricably linked. The process of creating new industries does not go forward without sweeping away the preexisting order.

Transportation provides a dramatic, ongoing example of creative destruction at work. With the arrival of steam power in the nineteenth century, railroads swept across the United States, enlarging markets, reducing shipping costs, building new industries, and providing millions of new productive jobs. The internal combustion engine paved the way for the automobile early in the next century. The rush to put America on wheels spawned new enterprises; at one point in the 1920s, the industry had swelled to more than 260 car makers. The automobile’s ripples spilled into oil, tourism, entertainment, retailing, and other industries. On the heels of the automobile, the airplane flew into our world, setting off its own burst of new businesses and jobs.

Americans benefited as horses and mules gave way to cars and airplanes, but all this creation did not come without destruction. Each new mode of transportation took a toll on existing jobs and industries. In 1900, the peak year for the occupation, the country employed 109,000 carriage and harness makers. In 1910, 238,000 Americans worked as blacksmiths. Today, those jobs are largely obsolete. After eclipsing canals and other forms of transport, railroads lost out in competition with cars, long-haul trucks, and airplanes. In 1920, 2.1 million Americans earned their paychecks working for railroads, compared with fewer than 200,000 today.

What occurred in the transportation sector has been repeated in one industry after another – in many cases, several times in the same industry. Creative destruction recognizes change as the one constant in capitalism. Sawyers, masons, and miners were among the top thirty American occupations in 1900. A century later, they no longer rank among the top thirty; they have been replaced by medical technicians, engineers, computer scientists, and others.

Technology roils job markets, as Schumpeter conveyed in coining the phrase “technological unemployment”. E-mail, word processors, answering machines, and other modern office technology have cut the number of secretaries but raised the ranks of programmers. The birth of the Internet spawned a need for hundreds of thousands of webmasters, an occupation that did not exist as recently as 1990. LASIK surgery often lets consumers throw away their glasses, reducing visits to optometrists and opticians but increasing the need for ophthalmologists. Digital cameras translate to fewer photo clerks.

And while your job may be one of those that will ride easily into our brave new future, the same may not be true of your stock investments. Companies show the same pattern of destruction and rebirth. Only five of today’s hundred largest public companies were among the top hundred in 1917. Half of the top hundred of 1970 had been replaced in the rankings by 2000.

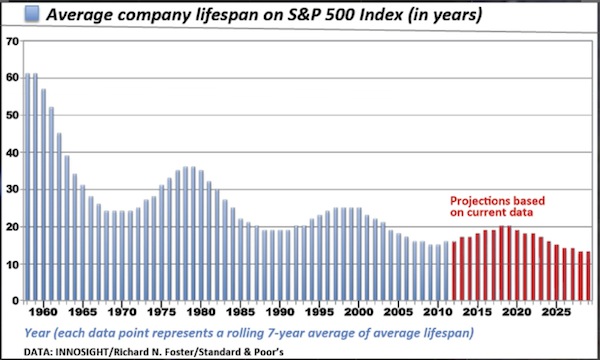

The chart below was recently produced by Richard Foster at S&P. What it shows is that the average lifespan of companies in the S&P 500 Index was about 60 years in 1960. Today they last about 15-20 years. That means we are currently replacing a stock in the index about every two weeks.

Since the index is representative of the largest US companies, that means that each year 25 big companies either can’t grow enough to keep up or are outgrown by other companies, otherwise fail or get merged; but in general terms it means that if you are invested in the S&P 500 Index, it is almost guaranteed that at least 10% of the companies in your portfolio are old dogs.

Blockbuster failed to recognize that the world was changing, and it was Netflixed, to coin a verb. (Actually I think it’s quite a workable word to describe what happens when a company fails to adapt. It gets Netflixed.) There is going to be a bright dividing line in the future between companies that “get” change and companies that don’t. Measuring companies by past performance and recent profit trends will no longer be enough in the Age of Transformation.

No industry is going to be safe. Within the next 10 years, solar technology will develop to the point where it will be cost-competitive with fossil fuels. Currently, the solar industry is growing at 30% a year; and while solar is only 1% of US energy consumption today, if we are able to keep up that compounding effort, it it could be almost 100% in 20 years. Solar roads? Possible. And yes, we need new batteries and storage systems, but those are on the way. What will your mother’s safe utility companies do?

In China they are literally 3D printing 3000-square-feet houses in a day! One company is planning to 3D print a car with 20 moving parts this fall, using advanced materials much stronger than steel and aluminum. Think AT&T is safe? The competition for new wireless systems is brutal. Both Facebook and Google are developing technologies to place “high-balloons” and permanent solar drones at 65,000 feet in order to blanket the globe with Wi-Fi. I’ve read estimates that a “mere” 40,000 such devices could do the job. Netflix itself is in danger of being Netflixed by Hulu and other competitors.

You can’t believe what they’re doing with robots and artificial intelligence. AI, long the poster child for disappointing technologies, is getting ready to go mainstream by the end of the decade.

Just for fun, look at this RadioShack ad from 1991. Essentially everything on that page is in a smart phone. And far more powerfully. And throw in a free camera. For a tiny fraction of the prices advertised then.

Now fast-forward 20 years. I’m not sure what our can’t-live-without-it computing and communication devices will look like, but they will probably be quite small, wearable, and a million times more powerful! We will likely be (or at least some of us will be) connected to our devices in rather unique ways. (Google Glass will seem so odd and quaint, which is kind of how it is perceived now.) Think of being able to access scores (hundreds?) of expert systems waiting in the cloud with answers on any topic, so that the solutions to the problems of improving our personal lives and our businesses will be limited only by our imagination in asking the questions (and doing the work to make those answers real). And we’ll be able to direct those AI experts to work together to come up with powerful, novel solutions. The cross-fertilization of technologies will soar!

Now imagine putting these tools into the hands of practically every person on earth who wants them. Along with all the other tools that are coming from all the other exponentially accelerating technologies. Especially life-altering will be the biotech breakthroughs. We won’t be physically immortal, but the things that kill most of us today will not be a problem. We will just get … older. And we will be able to repair a great deal of the damage from aging. Plan on living a lot longer and needing more money than you think.

I can see many of my readers rolling their eyes and saying it won’t happen in 20 years. Or 30 or 40. Things just don’t happen that fast, you say. But that is just your old Homo sapiens brain extending the past in a linear fashion into the future. Moore’s law tells us that the number of transistors on a chip roughly doubles every two years (and the chip drops in price). But other industries, like solar tech and genome sequencing, are on exponential paths that make Moore’s law look positively snail-like. If the power of exponential change keeps working – and it will – we will see more change in the next 20 years than we saw in the last 100!

I get lots of newsfeeds from services that list 3-5 new advances in some field every day. It can be overwhelming. (We have our own such free service here at Mauldin Economics, called Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest.) The time from proof of principle in the lab until rollout in the factory is dropping as well. We are now using over 200 different materials in our 3D printers, combined in ways that were never before possible. (We’re even starting to print human organs, a feat that I predict will seem like so “last-century” in 20 years). I am lucky in that I get to tag along every now and then with Pat Cox as he interviews the leading scientists and entrepreneurs in a wide range of industries. He does the groundwork in sorting through that gale of creative destruction, and I get to see the pick of his litter.

One of the risks in investing in technology, by the way, is not so much that your company might not discover some new, cool tech that blows away the competition, but that someone else might come along and do it even better and cheaper before you’re even out of the starting gate. You can be right about the tech and STILL lose money.

The thing that is going to be overwhelming to nearly all of us is the degree of acceleration of change as the years fly by. We are not psychologically prepared for it. The only way we will be able to adapt is to ignore that primal part of our brain that says change is bad and use our frontal lobes to rationally observe and choose a path forward. Just as Neanderthals gave way to Homo sapiens, we need to evolve, at least in our thinking, to become Homo rationalis.

All of our investments and our businesses – and our very lives – will be fundamentally changed, transformed by these two Super Trends we have looked at. Needless to say, we cannot turn our backs on the nitty-gritty details of the faltering global economy. We still have to read financial statements and government reports and stay on top of which central bank is doing what to whom, and to translate our research and analysis into smart, nimble investments. Simply knowing that things are going to change in technologically wonderful ways will not be enough. Acting too soon will be as frustrating and ineffective as not acting soon enough. We will continue to explore together in this letter to figure out how all the pieces of the puzzle fit.

I would like to remind readers that I will be part of an exclusive webinar with investment industry heavyweights Richard Perry and Jack Rivkin on Tuesday, June 24, at 1:00 p.m. EDT / 10:00 a.m. PDT, hosted by my partners at Altegris. Richard founded Perry Capital in 1988 and is one of the originators of event-driven investing – a very interesting strategy to look at right now, given increased corporate activity this year. My friend Jack brings more than 45 years of direct investing, research, general management, and investment management experience at leading financial institutions to his role as Altegris CIO. Unfortunately, this event is limited to qualified US investors. You can go to http://www.altegris.com/mauldinreg to sign up, and someone from Altegris will call and make sure you get an invitation. I hate to limit it, but that is the rule. (In this regard, I am president and a registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, member FINRA.)

Rome, Nantucket, New York, and Maine

I finish this letter on the train from Chiusi (in Tuscany) to Rome, where I will spend the next four nights. Tomorrow I am tourist, probably seeing the Vatican courtesy of a connection from Martin Truax. We met up in Cortona the other night, which turned into an adventure itself, and had dinner at a delightful outdoor restaurant overlooking the old town square, with 1,000-year-old walls as our backdrop. And a nearly full moon. Then I am in business mode, meeting with a series of corporate and government leaders and attending as much as I can of a very interesting conference organized by Banca IMI (the Investment Bank of Intesa Sanpaolo Group) and intriguingly titled “Back to the Future: Are Markets and Policy Makers Ready for Normality?” They have asked Christian Menegatti of Roubini Global Research and me to speak jointly to the main topic. Looking over the attendee list of government officials, bankers, and major market players is quite daunting, but we will try to provide a few useful thoughts. My first thought on hearing the question was, “What can be considered normal in Europe?” And upon reflection I am still trying to come up with an answer. Just saying.

Travel slows down this summer, with just a trip to Nantucket for a speech and to NYC for a few meetings in mid-July – and of course the annual Maine fishing trip. Even though Texas will be hot, I will enjoy being home for what will seem like an extended time.

As I am thinking a lot about change, I keep wondering how it will affect my family and friends. I know the unemployment number keeps falling, but good jobs seem problematical, and so many are going to disappear even as others appear, and that will mean learning new skills. Yet so much will not change. Humans will basically remain the same even as our tools improve. Family and good times with friends will still be important. We will still want to find meaning outside of ourselves. Most of us will still enjoy watching sports or listening to our favorite music. And serving others to take care of their basic needs will never go out of style. I hope to still be writing to you in 20 years, but I am not sure what form you will consume it in. I will adapt. And you will, too – you’ll need to.

They are calling Rome, so I guess that means it is time to hit the send button. It has been a relaxing two weeks, and I took much more time off than I had planned and read a few sci-fi books. I am enjoying Neptune’s Brood, by Charlie Stross, which offers a new version of money and economics in the far, far future (and is based on Bitcoin tech, for those interested). If you want to read a book about the near future and what will be possible with drones and AI, let me suggest Kill Decision, by Daniel Suarez. Frankly, it is the scariest book I have ever read. It is tech run amok, and the possibilities it raises are sadly more than real. While I do my best to be a cautious optimist, I admit to worrying about how some of our new tools will be used. God give us the wisdom…

Your relaxed and ready to get back to work (tomorrow!) analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

subscribers@mauldineconomics.com