The Pension Storm Is Coming To Europe—It May Be The End Of Europe As We Know It

- John Mauldin

- |

- October 3, 2017

- |

- Comments

BY JOHN MAULDIN

I’ve written a lot about US public pension funds lately. Many of them are underfunded and will never be able to pay workers the promised benefits—at least without dumping a huge and unwelcome bill on taxpayers.

And since taxpayers are generally voters, it’s not at all clear they will pay that bill.

Readers outside the US might have felt safe reading those stories. There go those Americans again… However, if you live outside the US, your country may be more like ours than you think.

This week the spotlight will be on Europe.

The UK Is Headed to a Retirement Implosion

The UK now has a $4 trillion retirement savings shortfall, which is projected to rise 4% a year and reach $33 trillion by 2050.

This in a country whose total GDP is $3 trillion. That means the shortfall is already bigger than the entire economy, and even if inflation is modest, the situation is going to get worse.

Plus, these figures are based mostly on calculations made before the UK left the European Union. Brexit is a major economic shift that could certainly change the retirement outlook. Whether it would change it for better or worse, we don’t yet know.

A 2015 OECD study found workers in the developed world could expect governmental programs to replace on average 63% of their working-age incomes. Not so bad. But in the UK that figure is only 38%, the lowest in all OECD countries.

This means UK workers must either build larger personal savings or severely tighten their belts when they retire. Working past retirement age is another choice, but it could put younger workers out of the job market.

UK retirees have had a kind of safety valve: the ability to retire in EU countries with lower living costs. Depending how Brexit negotiations go, that option could disappear.

Turning next to the Green Isle, 80% of the Irish who have pensions don’t think they will have sufficient income in retirement, and 47% don’t even have pensions. I think you would find similar statistics throughout much of Europe.

A report this summer from the International Longevity Centre suggested that younger workers in the UK need to save 18% of their annual earnings in order to have an “adequate” retirement income.

But no such thing will happen, so the UK is heading toward a retirement implosion that could be at least as damaging as the US’s.

The Swiss Are No Different Despite the Prudence

Americans often have romanticized views of Switzerland. They think it’s the land of fiscal discipline, among other things. To some extent that’s true, but Switzerland has its share of problems too. The national pension plan there has been running deficits as the population grows older.

Earlier this month, Swiss voters rejected a pension reform plan that would have strengthened the system by raising women’s retirement age from 64 to 65 and raising taxes and required worker contributions.

From what I can see, these were fairly minor changes, but the plan still went down in flames as 52.7% of voters said no.

Voters around the globe generally want to have their cake and eat it, too. We demand generous benefits but don’t like the price tags that come with them. The Swiss, despite their fiscally prudent reputation, appear to be not so different from the rest of us.

This outcome in Switzerland captures the attitude of the entire developed world. Compromise is always difficult. Both politicians and voters ignore the long-term problems they know are coming and think no further ahead than the next election

Switzerland and the UK have mandatory retirement pre-funding with private management and modest public safety nets, as do Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, and Hungary.

Not that all of these countries don’t have problems, but even with their problems, these European nations are far better off than some others.

France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Spain Are in Deep Trouble

The European nations noted above have nowhere near the crisis potential that the next group does: France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, and Spain.

They are all pay-as-you-go countries (PAYG). That means they have nothing saved in the public coffers for future pension obligations, and the money has to come out of the general budget each year.

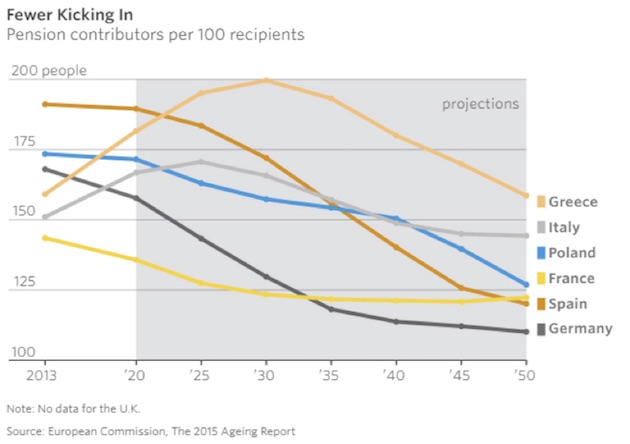

The crisis for these countries is quite predictable, because the number of retirees is growing even as the number of workers paying into the national coffers is falling.

Let’s look at some details.

Spain was hit hard in the financial crisis but has bounced back more vigorously than some of its Mediterranean peers did, such as Greece. That’s also true of its national pension plan, which actually had a surplus until recently.

Unfortunately, the government chose to “borrow” some of that surplus for other purposes, and it will soon turn into a sizable deficit.

Just as in the US, Spain’s program is called Social Security, but in fact it is neither social nor secure. Both the US and Spanish governments have raided supposedly sacrosanct retirement schemes, and both allow their governments to use those savings for whatever the political winds favor.

The Spanish reserve fund at one time had €66 billion and is now estimated to be completely depleted by the end of this year or early in 2018. The cause? There are 1.1 million more pensioners than there were just 10 years ago. And as the Baby Boom generation retires, there will be even more pensioners and fewer workers to support them.

A 25% unemployment rate among younger workers doesn’t help contributions to the system, either.

Overall, public pension plans in the pay-as-you-go countries would now replace about 60% of retirees’ salaries. Plus, several of these countries let people retire at less than 60 years old. In most countries, fewer than 25% of workers contribute to pension plans. That rate would have to double in the next 30 years to make programs sustainable.

Sell that to younger workers.

The Wall Street Journal recently did a rather bleak report on public pension funds in Europe. Quoting:

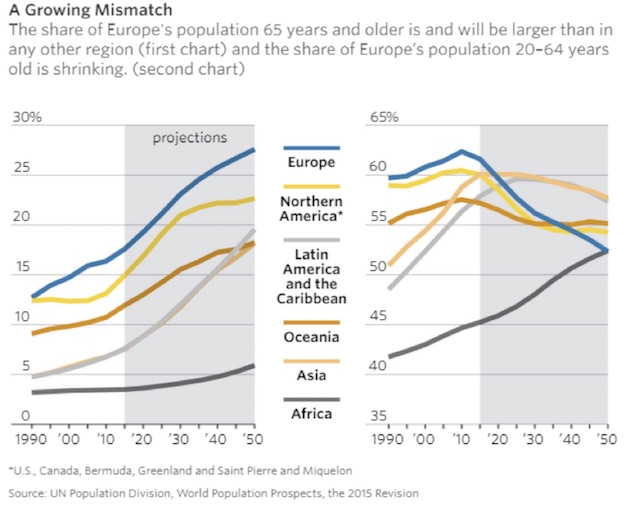

Europe’s population of pensioners, already the largest in the world, continues to grow. Looking at Europeans 65 or older who aren’t working, there are 42 for every 100 workers, and this will rise to 65 per 100 by 2060, the European Union’s data agency says. By comparison, the U.S. has 24 nonworking people 65 or over per 100 workers, says the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which doesn’t have a projection for 2060. (WSJ)

While the WSJ story focuses on Poland and the difficulties facing retirees there, the graphs and data in the story make clear the increasingly tenuous situation across much of Europe.

And unlike most European financial problems, this isn’t a north-south issue. Austria and Slovenia face the most difficult demographic challenges, right along with Greece. Greece, like Poland, has seen a lot of its young people leave for other parts of the world.

This next chart compares the share of Europe’s population that 65 years and older to the rest of the regions of the world and then to the share of population of workers between 20 and 64. These are ugly numbers.

Source: WSJ

The WSJ continues:

Across Europe, the birthrate has fallen 40% since the 1960s to around 1.5 children per woman, according to the United Nations. In that time, life expectancies have risen to roughly 80 from 69.

In Poland birthrates are even lower, and here the demographic disconnect is compounded by emigration. Taking advantage of the EU’s freedom of movement, many Polish youth of working age flock to the West, especially London, in search of higher pay. A paper published by the country’s central bank forecasts that by 2030, a quarter of Polish women and a fifth of Polish men will be 70 or older.

Source: WSJ

This Coming Crisis Is Beyond the Power of Politicians

I could go on on reviewing the retirement problems in other countries, but I hope you begin to see the big picture. This crisis isn’t purely a result of faulty politics—though that’s a big contributor.

It’s a problem that is far bigger than even the most disciplined, future-focused governments and businesses can easily handle.

Worse, generations of politicians have convinced the public that their entitlements are guaranteed. Many politicians actually believe it themselves. They’ve made promises they aren’t able to keep and are letting others arrange their lives based on the assumption that the impossible will happen. It won’t.

How do we get out of this jam?

We’re all going to make big adjustments. If the longevity breakthroughs that I expect to happen do so soon (as in the next 10–15 years), we may be able to adjust with minimal pain. We’ll work longer years, and retirement will be shorter, but it will be better because we’ll be healthier.

That’s the best-case outcome, and I think we have a fair chance of seeing it, but not without a lot of social and political travail. How we get through that process may be the most important question we face.

Join hundreds of thousands of other readers of Thoughts from the Frontline

Sharp macroeconomic analysis, big market calls, and shrewd predictions are all in a week’s work for visionary thinker and acclaimed financial expert John Mauldin. Since 2001, investors have turned to his Thoughts from the Frontline to be informed about what’s really going on in the economy. Join hundreds of thousands of readers, and get it free in your inbox every week.