The Italian Referendum Could Result in the Death of the Euro

- John Mauldin

- |

- August 31, 2016

- |

- Comments

BY JOHN MAULDIN

An important election is coming up, and I’m not talking about the US presidential election. The upcoming referendum in Italy this fall will have a major macroeconomic impact on the world. But hardly anyone outside of Italy is paying much attention to it—yet.

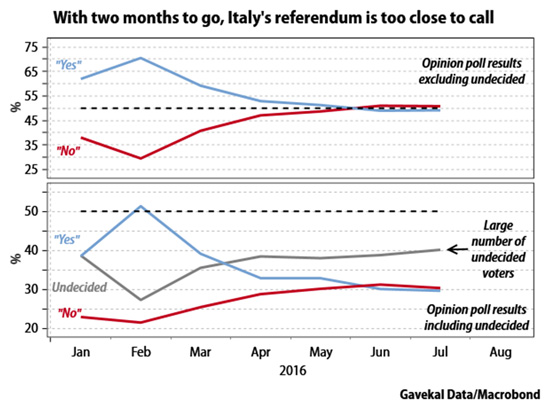

I’ve been saying for some time in interviews around the country that the referendum in Italy could have even more of an impact than the Brexit vote did in the UK. And like the Brexit vote, it is rife with emotion and political turmoil, making the outcome too close to call.

The current prime minister, Matteo Renzi, has basically bet his career on this referendum, which would allow him to enact much-needed reforms. In fact, they’re the same reforms that I have written about in my letters over the past five years and that I talked about in my previous two books.

Italy has about as sclerotic a governmental process as any country in Europe. And that is saying something. There is no end to corruption and crony politics. Each faction wants to keep the status quo and keep its perks but wants everybody else to give theirs up. If you’re a voter in Italy, your frustration is understandable.

This vote in Italy needs to go on your economic radar screen. If the “no” vote wins, Renzi has promised to resign. This would throw Italy into a political crisis. Then there would be a real potential to elect parties that would call for a vote on whether to stay in the European Union. And at this point, it is not clear what the Italians would decide to do.

Know this: The European Monetary Union does not work very well, if at all, without Italy. A “no” vote would be the death knell of the euro.

Nick Andrews, who writes for my friends at Gavekal, gives an excellent summary of the situation in Italy. And, it is worth every bit of your attention.

Renzi’s Great Gamble

By Nick Andrews and Stefano Capacci

Prime ministers come and go in Italy—four since the financial crisis—but precious little seems to change. The latest incumbent, Matteo Renzi, has pursued structural reform more energetically than his predecessors. But for all the progress he has made, he might as well have been wading through molasses. Now, in a bid to secure a popular mandate for his restructuring program, Renzi has bet his premiership on a referendum over badly-needed constitutional reforms. It is a high stakes gamble. If Renzi wins the vote, which is due in either October or November, his proposed measures will streamline Italy’s legislative process, breaking the parliamentary gridlock which has crippled successive governments, and opening the way to far-reaching economic reforms. If he loses, Renzi has promised to step down—a pledge that has turned the referendum into a popular vote of confidence in the unelected prime minister, his Europhile policies, and—by extension—Italy’s membership of the eurozone itself. As a result, a “no” vote in October will not just precipitate the fall of Renzi’s government; it could throw Italy’s long-term membership of the eurozone into doubt, plunging the single currency area once again into crisis.

Policy no man’s land

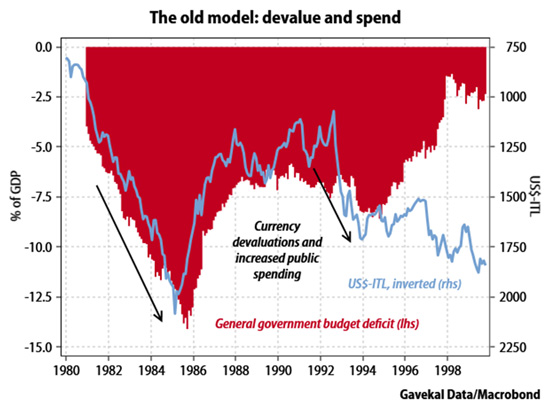

Italy’s fundamental problem is that it’s stuck in a policy no man’s land. Its old economic model, in place for much of the last three decades of the 20th century, relied on a combination of currency devaluation to maintain international competitiveness together with fiscal spending to support the poorer regions of the country’s south.

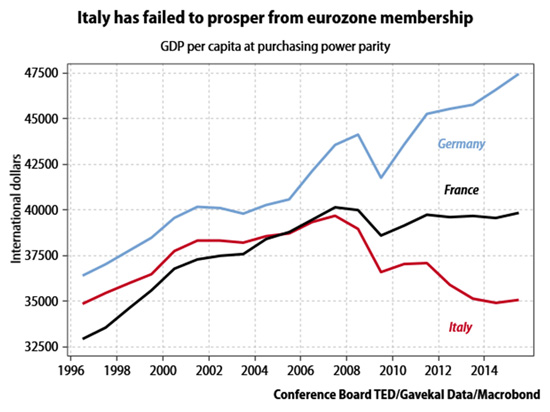

Signing up to the euro put an end to all that, preventing devaluations and prohibiting budget deficits at 10% of gross domestic product. However, the design of Italy’s bicameral parliamentary system, in which the upper and lower house—the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies—wield equal legislative power, made it almost impossible for any government to push through the structural reforms necessary for Italy to compete and prosper within the eurozone. The result has not just been depressed growth and relative impoverishment, but an outright decline in living standards as Italy’s real GDP per capita has slumped to a 20-year low.

Such a below-par economic performance has led to a build-up of bad assets on the balance sheets of Italy’s banks, where 18% of all loans are now classed as non-performing. In turn, this bad loan overhang has eroded the ability of the banking sector to extend new credit to the thousands of small businesses which are the engine of Italy’s economy and which normally power employment growth. The result is stagnation.

To stand any chance of escaping this low growth trap, Italy needs to enact wholesale structural reforms to enhance its competitiveness relative to its eurozone neighbors. Notably, it needs to make the labor market more flexible to encourage job creation, it needs to lower the barriers to entry that protect much of the country’s service sector, it needs to overhaul a judicial system so sclerotic that bankruptcy proceedings can last 10 years or more, and it needs to restructure its fragmented and dysfunctional banking system.

The prescription might be clear, but Italy’s political system makes enacting reform all but impossible. Renzi has already tried to overhaul Italy’s labor market by attempting to dismantle the generous protections that make it difficult and expensive for companies to dismiss staff, and which therefore encourage businesses to hire only temporary workers, heightening economic insecurity among the young.

But Renzi’s attempt ran into bruising opposition from Italy’s powerful and well-subscribed trade unions. The results were a watered-down reform package that entitles existing permanent staff to a near-guarantee of lifetime employment, and a severe dent in Renzi’s popularity from which he is yet to recover. It’s a familiar story in Italy. Entrenched interests—whether represented by local and regional political leaders, unions, protected professions, or established private sector companies—exert enormous influence over the political process. All profit from the status quo, which promises they will continue to benefit from special protections and payouts. And because of the equal balance of power in Italy’s parliament, which means the Senate can block government legislation indefinitely, the consequence is political—and economic—stagnation.

Bloated and wasteful

Renzi’s referendum aims to change that. The prime minister is seeking popular approval for constitutional reforms that promise to cut the size of the upper house from 315 to 100 senators. Under his proposals, senators will no longer be directly elected, but will instead be chosen by regional councils, nominated by the mayors of big cities, or—in the case of five—be appointed by the Italian president. The reform will cut the costs of the notoriously bloated and wasteful upper house, where senators have traditionally enjoyed lavish expenses and generous pensions. Most importantly, it will downgrade the political power of the Senate so that it will no longer be able to obstruct government legislation entirely, but only to propose amendments that will be adopted at the discretion of the lower house (although the Senate will retain a say on constitutional matters, including the ratification of European Union Treaties). The objective is to increase the executive power of the government, and to tackle entrenched interests with additional measures that allow for new laws to facilitate popular referendums and to promote citizen participation in the political process.

Unlikely alliance

However, powerful forces are arrayed against Renzi, and a “Yes” vote is far from assured. The proposed reforms have attracted opposition from establishment voices who benefit from the current arrangements. They have also drawn fire from constitutional lawyers and anti-establishment parties, including the populist 5-Star Movement, which argues the 50% simple majority needed to win the referendum is too low for constitutional changes that promise a concentration of political power unprecedented since the formation of the Italian republic in 1946.

Perhaps more importantly, Renzi’s pledge to resign in the event of a “No” victory has raised the possibility of a protest vote against the prime minister himself—the third unelected head of government in succession—from a broad cohort of the electorate, which is thoroughly disillusioned with Italian politics. Increasingly disgruntled, these voters are sick of the corruption and self-interest of politicians, and fed up with painfully austere policies that they believe to be dictated from Brussels and Berlin, and which they hold responsible for Italy’s poor economic performance.

The chances of a “Yes” vote in the referendum have not been improved by the slump in Renzi’s personal popularity following last year’s attempt to reform the labor market, and a series of small bank restructurings that saw retail savers “bailed-in”—forced to take losses—under new European Union banking regulations. From 40% after Renzi entered office two years ago with optimistic promises of reform, the approval rating of the prime minister’s PD party has fallen to little better than 30% today, much the same as that of the opposition 5-Star Movement. As a result, with two months to go the referendum is too close to call. Opinion polls indicate the “Yes” and “No” camps are running roughly equal, with a large proportion of voters still undecided.

If Renzi loses the referendum, not only will Italy remain in policy limbo, but it is highly likely his subsequent resignation will trigger a parliamentary election. Under new election laws passed last year, if a party fails to win 40% in the first round of voting, the top two parties go through to a second round. The latest opinion polls put Renzi’s governing PD party on 31% and the 5-Star Movement on 29%, with the next two largest parties—Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and the anti-establishment Northern League—level pegging on around 13%.

In recent years, Renzi’s PD government has represented the best hope for structural reform and economic modernization. But even if the PD party were to win a post-referendum election, there is a risk that, following Renzi’s resignation, the left wing of the party would wrest back control from the reformist center-right faction, damping hopes for further restructuring. Such a swing to the left would hardly be unique to Italy. In the UK, the militant left has captured the leadership of the main opposition Labour Party. In Spain, Podemos has split the left wing vote, and in France the ruling Socialists have come under pressure in the polls from the radical and Euroskeptic Left Party led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

At the moment, an election victory for the 5-Star Movement, which identifies as neither left nor right, appears at least as probable as a second round win for the PD. The Movement has already scored significant victories in mayoral elections in Rome and Turin and enjoys increasing support across the country. Its broad stance is anti-establishment and in favor of direct participatory democracy rather than representative democracy, which it regards—with some justification in Italy—as an invitation to corruption. Beyond that, however, its platform is so vague that it is hard to pinpoint any concrete policies, except its call for a referendum on Italy’s membership of Europe’s single currency.

Leadership vacuum

Perhaps the biggest problem for 5-Star, however, is that it has no clear leader. Its founder and leading voice, Beppe Grillo, was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter in 1980 following a fatal road traffic accident, and so cannot run for public office under Movement rules barring candidates with criminal records. Without Grillo, the parliamentary party would be leaderless, meaning 5-Star has no obvious prime ministerial candidate even should it secure a majority in the election.

All this means that the possibility of a “No” vote in Italy’s constitutional referendum come October or November is the biggest clear and present danger to the euro’s survival. Both 5-Star and the Northern League are promising a plebiscite on euro membership should they come to power in a post-referendum election. That does not mean a vote on Italy’s eurozone membership would lead directly to its exit—many likely “No” voters in this year’s constitutional referendum favor continued euro membership. However, a “No” vote come October would effectively be a vote against the structural reforms needed to ensure Italy’s economic growth and prosperity within the eurozone.

In other words, in the event of a “No” vote in October, the only economic choice for Italy would be between continued stagnation, or a return to the old economic model of successive devaluations. The latter course would naturally mean exiting the eurozone anyway. But even if Italy were to take that path, it would hardly be a less painful way to restore the economy to health. Whether inside or outside the single currency, Italy still needs structural reform to ensure future growth. The only potential benefit to leaving the eurozone would be that deep devaluation of a reconstituted lira could help to ease some of the transitional pain (although it is probable the palliative effect would be more than offset by the additional economic and financial damage wreaked by an exit).

Europe in microcosm

Clearly investors should be concerned. Italy is the third biggest economy in the monetary union and one of its core members. Its departure would surely hasten the break-up of the whole euro project. What’s more, the political and economic tensions within Italy ahead of October’s referendum mirror those at work across the eurozone as a whole. In Italy, the wealthy north makes up the industrial heartland which drives the economy, while the south is underdeveloped and poor. There is little enthusiasm for structural reforms, and throughout the country, populist movements—which promise to tear down the self-serving political establishment—are rapidly gaining ground.

Italy is the wider eurozone in microcosm. In the EU as a whole, progress towards creating the political and economic institutions that could ensure the success of the single currency project have been comprehensively obstructed by narrow—but deeply entrenched—national interests. This failure to advance, and the economic hardships and sense of disempowerment that have resulted, has fueled the rise of populist political parties from Greece to Finland—parties that are challenging an increasingly distrusted political elite and questioning not just the status quo, but the whole European project. If Renzi wins come October, the eurozone has fresh hope. But if he fails, Italy fails—and very likely the eurozone fails too.

Subscribe to John Mauldin’s Free Weekly Publication

Each week in Outside the Box, John Mauldin highlights a thoughtful, provocative essay from a fellow analyst or economic expert. Some will inspire you. Some will make you uncomfortable. All will challenge you to think outside the box. Subscribe now!