John Mauldin: My Infrastructure Plan to Save the US Economy

- John Mauldin

- |

- October 12, 2016

- |

- Comments

BY JOHN MAULDIN

Infrastructure. Most people think of roads and bridges when they hear the term. But we really should think of infrastructure as the things that allow us to move food, energy, water, products, people, and information.

It’s our rail and trucking systems. It’s our electric grid. It’s our telephone system, Internet, and other information systems. To some degree, it’s our school systems. It’s the things that make it possible for businesses and governments to provide the services and goods we all expect.

You might respond that the roads and bridges are just fine and we don’t need more boondoggle spending. That may well be true wherever you live. But it is certainly not true for the nation as a whole.

Infrastructure Report Card Highlights Major Problems

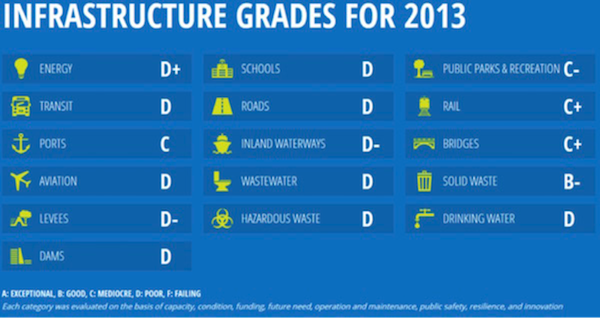

The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) publishes a national Infrastructure Report Card every four years. The last one was in 2013, so it’s a bit dated. While I’m sure that a few of the problems have resolved, there are probably enough new ones to replace them.

So, here is your report card, America. Brace yourself, it’s not good.

We all assume that when we flip the switch, the light will go on; and when we set the thermostat, the heat or air-conditioning will turn on. We assume these things are automatic—but they have to be maintained, and we are not maintaining them well.

Serious Problems Require Serious Money

According to the Federal Highway Administration’s Bridge Inventory, 146,633 out of 604,474 bridges in the US are structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. That’s 24.3% of all bridges. Bridges are built to last about 50 years, and today’s average bridge is 45 years old. See the problem?

Let’s look at dams. In Texas, 1,046 non-federal dams are rated “high hazard.” That means their failure would bring a probable loss of life. Will they fail? No one knows because most of them have no regular inspections or maintenance. There’s about one inspector for every 1,400 dams in Texas. Alabama has none. The average dam has a life of about 50 years, and many are much older than that.

Let’s look at water. The Center for American Progress reports that there are 240,000 water main breaks every year, and as much as 25% of the treated water that enters the distribution system is lost through leakage. There are 75,000 overflows every year from our sewage system, and they dump something like 900 billion gallons of untreated sewage into our lakes, rivers, streams, and bays.

The American Water Works Association estimates it will take $1 trillion to repair and replace the drinking water system over the next 25 years. It takes $3 billion a year just for emergency repairs.

Then there’s the outdated electrical grid. One estimate is that we lose about $49 billion a year to power outages. The solution is something called a Smart Grid, but that’ll cost tens of billions of dollars.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The ASCE estimated it would take $3.6 trillion to repair our infrastructure back in 2013. Do you care to bet that the figure will top $4 trillion the next time they do an estimate? And that’s just to repair and rework what we have right now. That is not what will be needed to actually propel us into the 21st century.

The total could be a multiple of that over the next 10 to 15 years. But if we pay our dues and do that work, then the next generation will get something worthwhile for their tax money rather than the close to $20 trillion worth of debt that we have now, which has produced damn little.

My Infrastructure Plan

First, I would propose that Congress authorize something along the lines of a Ginnie Mae bond for infrastructure spending. Ginnie Mae bonds have the full faith and credit of the US government behind them but are paid for by the homeowners who pay their mortgages. The bonds allow them to get cheaper mortgages.

Congress should then require the Federal Reserve to put those bonds on its balance sheet, selling Ginnie Mae bonds if the Fed wants to maintain its total asset base. The Ginnie Mae (and Fannie and Freddie) bonds would be readily bought back by the market if they were available.

The bonds would fund projects pursued by cities, counties, and states that have a tax base or other resource to pay for the bonds. (I do not want to go into this in detail here, but there are some legal prohibitions on certain types of government infrastructure spending.)

It’s clear that you could put a small surcharge on a local water bill to pay for rebuilding and modernizing the local water system. Ditto for the electric grid.

Roads are trickier as there has to be a tax base willing to carry the load. But an infrastructure bond guaranteed by the US government would carry a much lower interest rate. And there are ways to make that rate even lower.

US 30-year bonds are now at 2.3%. If you allowed local and state governments to borrow only for new infrastructure at 2.3% and created willing markets for their bonds, we’d see a lot of infrastructure being built.

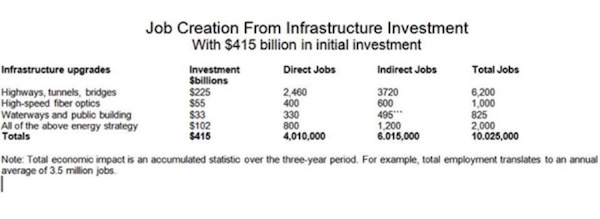

The next chart shows that an investment of $415 billion could create more than 10 million jobs.

My guess is that the spending would not really create 10 million jobs. But even half that number would change the nature of employment for many Americans who’ve lost manufacturing and other jobs and who have the skills to build what we need.

The point here is that such an infrastructure program would create a large number of jobs and boost an economy struggling through a recession. If the program were started early enough in the next administration, it might even keep us out of one.

Checks and Balances

To keep this from becoming a huge boondoggle, I would create an independent commission of 10 to 12 businesspeople who have not been elected politicians for at least 10 years. Their role is to sift through the proposed projects and make sure they’re real-world projects with long-term benefits and not just somebody’s pet project.

The commission members would have to recuse themselves from any vote on a project in their home state. Their mandate would be to make sure that each proposed project makes sense and that there is at least a 95% probability that the local or regional tax base could pay for the project.

I would require that every entity that borrows money (a local jurisdiction, county, or state) actually hold a vote to approve the bond, with language clearly indicating that taxpayers or users of the service will be responsible for paying for it. If the funding to repay the bond is determined by independent auditors to be suspect, then local taxpayers would have to agree to a special tax to pay for the bonds. Toll highways move to the front of the line.

My preference would be that the low bid wins and no requirement for union labor, at least in states that are right-to-work states. If taxpayers want to pay extra for union labor, that’s their choice.

Government Should Subsidize Infrastructure Bonds

Now, let me get really controversial. The US has spent hundreds of billions of dollars trying to fix Iraq and Afghanistan and on other projects around the world. What if we renewed the focus on our own needs?

If the US government subsidized these infrastructure bonds by 2%, then local governments would pay (at today’s rate) about 0.3% in total interest. Tack on an extra 10 or 20 basis points for servicing and the cost of the commission and losses, and a local government could borrow at about 0.5%. If the cost ends up higher, then the servicing cost goes up by 10 basis points.

The point is to make local governments pay for their projects, less the subsidy from the government for interest rates. Essentially, that subsidy is a rounding error in the total cost, and it would allow governments to start projects today and have 30 years to pay them back.

I’d provide the subsidy for a limited time (say four years) to encourage infrastructure projects to get off the ground now and kick-start employment. That would help reduce income inequality more than any ridiculous transfer system that takes money from the rich and tries to give it to the poor.

Let’s say we could actually deploy $3–4 trillion in infrastructure spending over the next 10 years. If we assume a subsidy cost of 2% for the bonds, then 2% of $2 trillion is $40 billion a year. That’s about 1% of our total federal expenditures. It is only about 7% of our defense budget.

Rebuilding our water systems would save up to 20% of the water we use and eliminate the massive costs for emergency repairs. It would actually pay for itself.

What Happens if We Do Not?

If we do not do something like this when we go into recession—especially if Hillary Clinton wins—the same central bankers who are running the system today will give us the same tired monetary programs with the same lack of results. Except this time, unemployment will be higher and the recovery will leave us looking more like Europe and Japan.

Get a Bird’s-Eye View of the Economy with John Mauldin’s Thoughts from the Frontline

This wildly popular newsletter by celebrated economic commentator, John Mauldin, is a must-read for informed investors who want to go beyond the mainstream media hype and find out about the trends and traps to watch out for. Join hundreds of thousands of fans worldwide, as John uncovers macroeconomic truths in Thoughts from the Frontline. Get it free in your inbox every Monday.