5 Maps That Explain The Modern Middle East

- George Friedman and Kamran Bokhari

- |

- June 29, 2017

- |

- Comments

BY GEORGE FRIEDMAN AND KAMRAN BOKHARI

Nation-states are the defining feature of the modern political era. They give people a collective identity and a pride of place… even when their borders are artificially drawn, as they were in the Middle East.

However, transnational issues like religion and ethnicity often get in the way of the notion of nationalism. Those can’t be contained by a country’s borders.

Arab nation-states are now failing in the Middle East. Their failure is mainly due to their inability to create viable political economies. Transnational issues—especially the competition between the Sunni and Shiite sects of Islam—however, amplify the process.

The Failure of Pan-Arabism

Transnational issues have long plagued the modern Middle East. Major Arab states like Egypt, Syria, and Iraq began to flirt with pan-Arabism. It’s a secular, left-leaning ideology that sought political unity of the Arab world. It promoted a kind of nationalism that defied the logic of the nation-state.

Pan-Arabism failed because it couldn’t replace traditional nationalism with something that had never existed in history. But the countries that rejected it never really developed into viable political entities.

The coercion of state security forces was what hold them together, not the ideology.

Since the 1970s, these countries have been challenged by another transnational idea, Islamism (or political Islam). It has proven to be far more effective than pan-Arabism. The movement has spread throughout the Middle East.

It has taken root not only among Sunni Arabs, but also among Shiites. In fact, the Shiites were the first to create an Islamist government when they toppled the monarchy in the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Sunni Islamists would not hold traditional political power until after the so-called 2011 Arab Spring. But their power was short-lived.

The Origins of the Islamic State

The anarchy of the Arab Spring was fertile ground for jihadists, especially for the Islamic State. It became the most powerful Sunni Islamist force in the region. What underlay its success was the group’s ability to exploit sectarian differences in the region.

The Baathist regime in Iraq was replaced by a Shiite-dominated government that Sunnis had tried to keep from power.

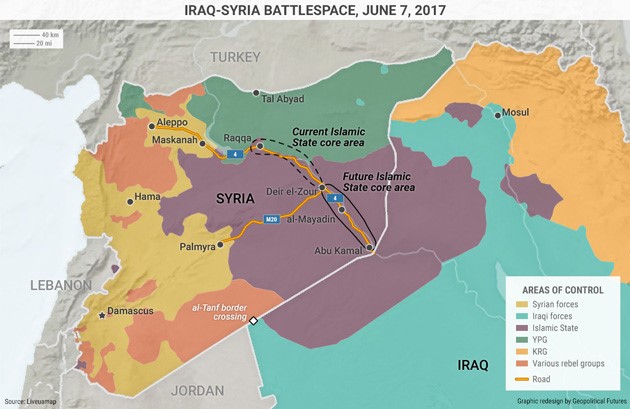

Likewise, the Islamic State, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey strived to take over the Sunni rebellion in Syria, which had been led by a minority Shiite government. The Islamic State was the best positioned to exploit the situation. They created a singular battlespace that linked eastern Syria with western Iraq.

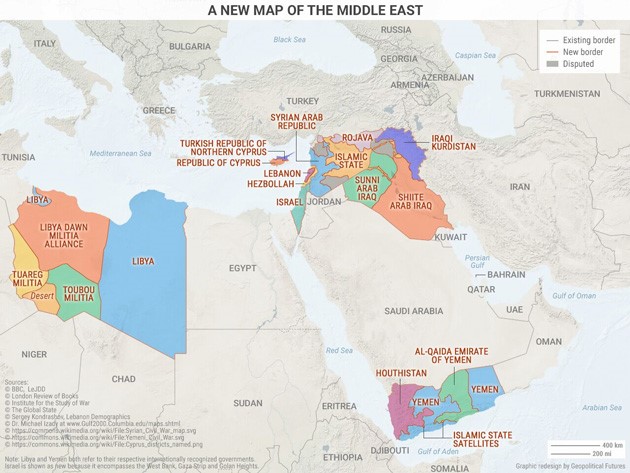

In doing so, it has destroyed what we have come to know as the sovereign states of Iraq and Syria.

Iraqi and Syrian nationalism can’t really exist if there is no nation. The Islamic State has lost some territory recently. But its losses appear to benefit the sectarian and ethnic groups that happen to be there, not the nations that owned the land.

In Syria, Sunni Arab forces are not all that interested in fighting the Islamic State. The only two groups that are willing are the Syrian Democratic Forces, which are dominated by Kurds who are trying to carve out their own territory, and Syrian government forces, who want to retake the areas that IS seized after the rebellion broke out.

Nationalism Replaced by Sectarianism

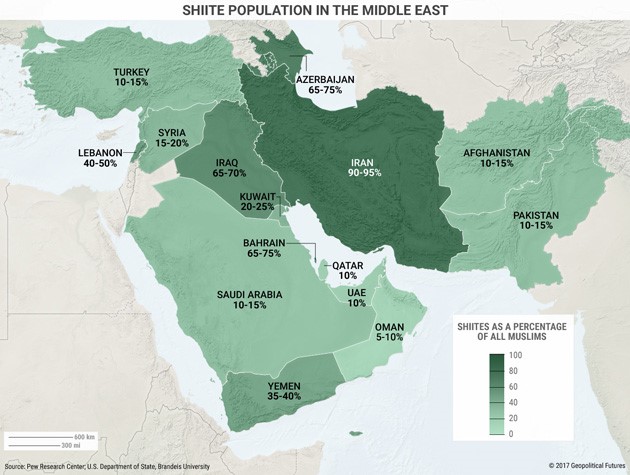

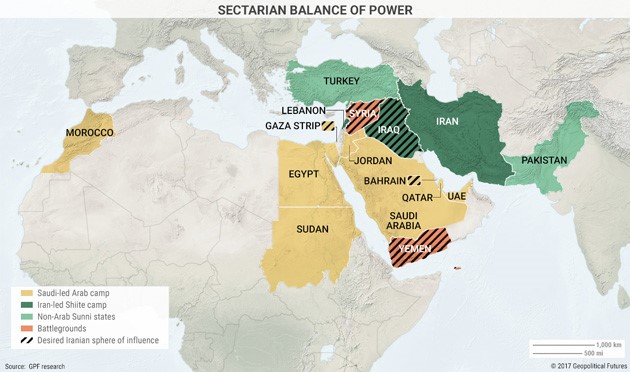

Sectarianism now stands in place of nationalism in the modern Middle East. On one side are the Sunnis, led nominally by Saudi Arabia. On the other are the Shiites, led nominally by Iran.

The Sunni bloc is in disrepair; the Shiite bloc is on the rise. The fact that Iran is Persian has in the past dissuaded Arab Shiites from siding with Tehran, but Saudi efforts to prevent the Shiite revival (not to mention the rise of the Islamic State) have left them feeling vulnerable.

They are willing to set aside their differences for sectarian solidarity.

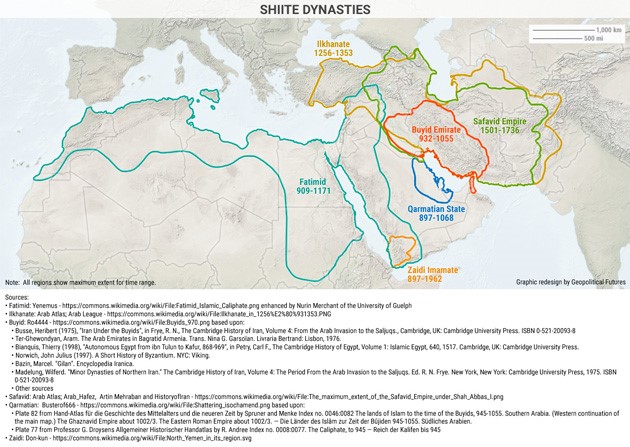

There’s historical precedent for what’s happening in the Middle East. In the 10th century, the Shiite Buyid and Fatimid dynasties came to power because the Sunni Abbasid caliphate began to lose its power.

Shiite dynasties ultimately could not survive in a majority Sunni environment, especially not after it came back on top from around 1200 to around 1600. The Shiites rebounded in the 16th century in the form of the Safavid Empire in Persia, which embraced Shiite Islam as state religion.

Power changes hands cyclically, about every 500 years.

And now, with Sunni Arab unity on the decline and with jihadists challenging Sunni power, the Shiites are in the position to expand once again. They are a minority, so it’s unclear just how far their influence can actually spread.

But what is clear is that modern nationalism is being replaced by medieval sectarianism.

Grab George Friedman's Exclusive eBook, The World Explained in Maps

The World Explained in Maps reveals the panorama of geopolitical landscapes influencing today's governments and global financial systems. Don't miss this chance to prepare for the year ahead with the straight facts about every major country’s and region's current geopolitical climate. You won't find political rhetoric or media hype here.

The World Explained in Maps is an essential guide for every investor as 2017 takes shape. Get your copy now—free!